Many people boast they “tell it like it is” … but I like to “tell it like it was”.

Because it’s not a good idea to live in a continuous present. It is convenient, but not thoughtful.

If we don’t value our own past, then we will be more easily subsumed by predator cultures. Until, effectively, we disappear.

The people who make the movies always win the war.

That’s why I see the Queensland State Library’s Queensland Memory section as crucial.

Shakespeare summed this up 422 years ago in Hamlet: “We have some rights of memory in this Kingdom.”

An example:

When I was working as a journalist in Hong Kong in 1964, I was sent to Macau to write a story about five architects sent out by the Portuguese government to save the magnificent façade of the Cathedral of St Paul’s – built by the Jesuits while Hamlet was being written.

But, even more importantly, they were there to save the cobblestone streets, the old unpainted houses, and, in particular, their gorgeous shabby pink exterior shutters.

I was only 23, so I asked the five architects, pen poised over notebook, why the hell is Portugal going to all this trouble?

The architect in charge answered:

“The dwellings a society builds tells who they are and where they came from: so – unless you are a conqueror – you should not knock them down!”

Seven years later, I came back home to Brisbane.

It was by then the 1970s and, for the first time, I understood what her words meant.

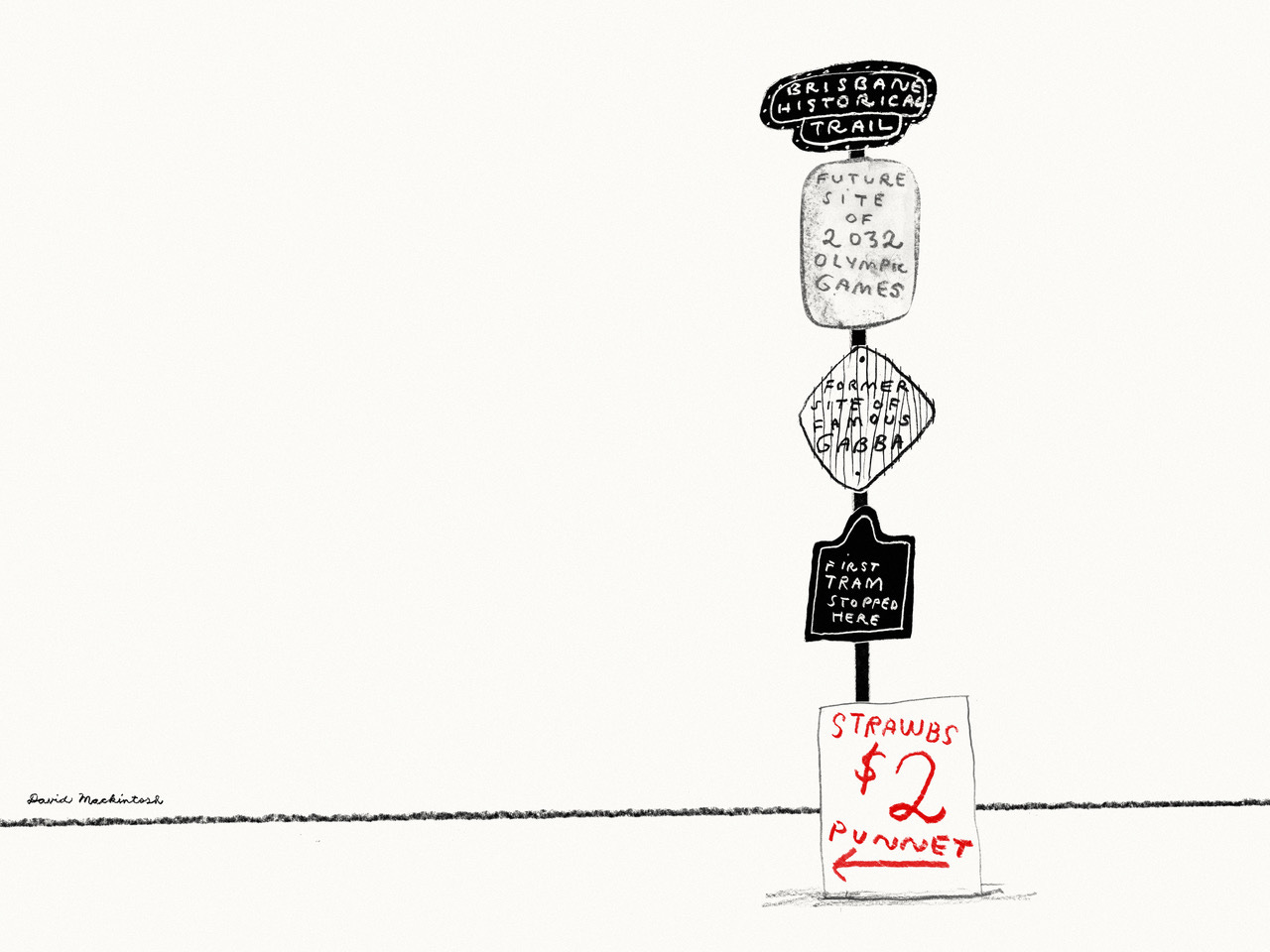

The open, airy silver bullet trams that bestrode the entire sub-tropical city – their Conductors and Motormen wearing distinctive French Legion caps – were all gone.

Some trams were even burned in the street: as if we were ashamed of them.

The timber Milton Tennis Stadium – where the Australian Open was held every four years, where the Davis Cup Challenge Round Final was contested time and again – this old arena was turned into firewood.

And then there was The Gabba.

It wasn’t Lords, or Old Trafford, or The Oval, but its tin-and-timber stands and the grassed hill shaded by enormous oak-like fig trees put you in mind of cricket’s origins in an English village.

The Gabba was charming, distinctive, and shady.

All gone.

And now the concrete monstrosity that replaced it is soon to be replaced by an even bigger concrete monstrosity.

The words of that Portuguese architect became especially poignant for me as 1970s and 1980s “progress” hit Queensland.

We were supposed to be proud of all the changes, of all the new things: but some of us could only see what was no longer there.

Our old Queensland houses.

In every street they were being knocked out, creating gaps like missing teeth: the worn, dented, honey-hued floorboards always pre-sold before a nail was removed — to make “antique” furniture.

The timber stumps made perfect retaining walls for the concrete-slabs taking over the suburbs.

In Brisbane many of these old homes were zoned “B”: which meant they could be replaced by a six-pack block of flats. I don’t know what the “B” stood for, but it sometimes seemed it stood for “Burning” because so many went up in flames.

Ever since, elected officials announce they’re “saving the old Queensland houses” — but it never stops.

Telling it how it was: they’ve been saving all the old Queensland houses … until there are none left.

In 1971 The Australian in Sydney hired me, aged 30, saying: “You’ve been a foreign correspondent in a lot of bizarre, strange, weird places around the world … so we want you to be our foreign correspondent in Queensland.”

Like everyone down south, The Australian’s editors couldn’t understand why Queensland saw things differently from the rest of the country: despite the fact that the sun, the wind, and the rain are different up here.

So they asked me to travel throughout the state interviewing people to write a series of articles on: “Why Queensland Is Different”.

To confirm all their prejudices I called my series … “The Difference between a Queenslander”!

But they didn’t get the joke.

My last stop was the City of Ipswich.

It was 38 degrees, the middle of summer. I stood in the main street asking women with prams, screaming hot babies, and railway fettlers: WHY?

Why are we so different?

Getting nothing, I stopped an old curmudgeon in a felt hat but – in answer to my question – he asked me one.

“Haven’t you done anything interesting in your life?”

A bit annoyed, I told him I’d written articles in Peking, Djakarta, West Papua, Singapore, London, Hong Kong, Danang, Saigon…

I thought I had the old codger. But no!

“Well,” he said, “if you’ve done all that … then why are you standing on a street corner in Ipswich on the hottest day of the year asking stupid questions?”

I said: “You’re right” and drove back to the office in Fortitude Valley where I wrote about the little things that made Queensland different: statistically we had bigger feet, for one thing.

National shoe store chains observed this: attributed to the fact that most Queensland schoolchildren “wear bare feet”, and adults wear thongs.

You might think a thong isn’t much evidence to go on, but archaeologists find a little thing like an Etruscan vase and learn about an entire society from it. They find a shard of pottery that tells them there were early humans who worshipped a woman.

It’s the same with our little shards of history.

Little things say much more than you might think.

In Peking in 1965 a Communist official warned me: “a vase of flowers on a table is a political statement”.

I guess like George Orwell’s aspidistra.

One thing that stands out from all the letters and emails I receive about my books and stories is that readers tend to respond most passionately to the little things.

I’ll tell you just how little.

In 1990 I got a letter from the owner of Chocolate Photos in New York, who had just read Over the Top with Jim. He wrote:

… the memory of the water running down the gutter and putting a paper boat into it devastated me.

I have been away from Brisbane 30-odd years … Your book has inspired me to go back to my memories.

In 2004, Brian Bacon, of Oxford Leadership Academy in the UK (the brother of the Brisbane art dealer Philip Bacon) wrote:

I’m an Annerley Junction Old Boy who has been living abroad — London, Stockholm, Geneva, Mexico City, Hong Kong and Chicago — for 15 years.

I picked up your Working for Rupert to kill a few hours on the Sydney–Bangkok sector and cried with delight the whole time … much as I did with Over the Top with Jim.

You’ll never know how much it means to people like me to reconnect with our roots.

A few months ago I was flying Chicago–New York in the McDonald’s company jet with fellow Aussie CEO of McDonald’s, Charlie Bell. We were watching the film Ned Kelly… I had tears rolling down my cheeks as I listened to the sounds of the Aussie bush.

I couldn’t stop sobbing.

Charlie was also wet-cheeked and he looked at me and said “Mate, what are we doing?”

My father Fred was brought up in an orphanage in Western Australia … and opened the Lunns for Buns cakeshop at Annerley Junction in working-class south Brisbane.

After Over the Top with Jim came out, I got a letter from a Dr Ray Bailey who said he used to organize picnics in Brisbane for orphans and kids in institutions. He wrote:

I remember approaching the proprietor of a cake shop at Annerley Junction seeking a donation of goodies for the children. I was told to come back at closing time when I could have anything that was left unsold.

He then told me that, if there was nothing left, it would mean that he had had such a good day that he would then be pleased to bake something specially: “How many kids did you say?”

We not only need to hold on to this past – these little shards of history – but we also need eyewitnesses to record what actually happened.

In West Papua (once Dutch New Guinea) in 1969 the United Nations, no less, oversaw an “Act of Free Choice” for the 800,000 Papuans.

Did they wish to become part of Indonesia?

In fact, no “Free Choice” actually occurred … but the little things I kept from there still tell the true story today.

Like the blood-soaked letter hidden in a conch shell begging me (and the only other reporter there, Dutchman Otto Kyuk) to tell the world that Papuans who spoke out were being killed.

There would be no One Man One Vote; no such thing as a secret ballot.

In Vietnam in 1967 the US military criticised reporters for looking at “pin-pricks” of the War … saying the Generals were seeing “the Big Picture”.

It turned out the “the little pin pricks” were right.

As my friend, reporter Pham Ngoc Dinh, said: “America not know who is enemy, who is friend.”

TIME Magazine was in the office next door to ours in Saigon.

Dinh later found out that TIME Magazine staff reporter, Pham Xuan An, was, at the same time, all along a Viet Cong Colonel (promoted to Major-General after the Fall of Saigon and named: “Viet Cong Hero in the South”).

This was ironic because TIME reporters would complain to me about the memos they kept getting from Head Office in New York which said:

“If you’re not going to write victories, then we’ll write them for you.”

TIME Magazine desperately wanted the War won, but – by having a Viet Cong Colonel for 10 years interviewing all the high-ranking American officers about their future manoeuvres – TIME was complicit in the defeat.

While working for Rupert Murdoch for 17 years – including writing Rupert’s own Chief Executive’s Review for him in his 1987 Annual Report – I kept everything.

And I’ve continued to do so … so that future researchers will be able to assess more accurately this Australian who became one of the most powerful humans on the planet.

There are many items I didn’t have when I wrote my Working for Rupert book. Like the following little things which I received 11 years later:

Rupert started The Australian in 1964. Every day for months he put down in writing a one-page typed critique on that day’s paper … and then pinned it up on the editorial noticeboard for all to see.

These pages show what was important to Rupert when he was a 33-year-old creating his own national newspaper from the ground up.

As an example, the notice he pinned up on Feb 10 1965:

“For reasons beyond me, cricket is coming back very strongly as a major sport…”

Or how about this on Feb 23:

“A very disappointing paper today.

“From a quick read, there are 35 mistakes!”

Rupert listed bad punctuation, mixed tenses, six people in a photo but only five names…

“The block-lines are sloppy” he wrote, “people in pictures should be named from left to right! [Tell them that now!]

“Artists didn’t clean up the main picture: NO EXCUSE” … misplaced apostrophes, misspelt names, incorrect capitalization…

At the end Rupert added:

“And I haven’t even read the paper carefully … yet.”

Rupert obviously knew little things created a successful newspaper.

The first time I heard about the importance of “little things” was when Jan Power gave a speech. In her day Jan Power was actor Bille Brown’s landlady – and also Brisbane’s cultural commentator.

Jan quoted JB Priestly, the famous English writer, who said:

“If I had my time again, I would write about the small things in life …

“There are wars all over the planet, but we have no control over them, so it is the very small things – and the importance we place on them – that is of greater interest to all the people on the planet.

“What intrigues us is this microscope placed on our personal adventures which makes us what we are … shapes our lives … and makes us remembered by those around us.”

Then Jan Power added:

“This is the Hugh Lunn system.

“He remembers the singlet he wore on the Gold Coast; the milkshakes at the Bikini Bar in Surfers; the heart-shaped sponge-cake his father baked every day and put in the shop window, saying “this’ll make some fella easy to love tonight”.

And, how Fred would say: “you can always tell a Queenslander … he’ll be carrying a pound of rainbow cake under his arm.”

Jan ended: “Hugh looks into the tiny details of our lives; how small it doesn’t matter.”

David Mackintosh illustrations © profuselyillustrated.com

I recall when the "Courier Mail" bought the "Telegraph". My old man commented, "That might upgrade their grammar and spelling." Nope, the CM went down. Then there was the "Truth". Had a mate working for a loan company. His job, find out why monthly payments hadn't been made. His comment after reading their article, "Well, they spelled my name right."

Must admit, got most of my 'news' in the Carlton Theaterette, and later the Vogue. (Before television.)

Another superb piece Hugh ..loved Rupert Murdoch's comments on the daily paper. I don't read newspapers much these days, but when I do can almost guarantee there will be errors on every page...must drive Rupert nuts !!