An Unusual Friendship

It’s 50 years this month since the Whitlam government recognised China.

When I returned home to Brisbane in 1971, aged 29, after seven years overseas I was surprised that – although I’d worked as a foreign correspondent in Beijing, Hong Kong, London, Saigon, Singapore and Djakarta – The Courier-Mail wouldn’t give me a job.

“Unfortunately for you,” they said, “a couple of bright young men from Sydney have applied.”

The only work I could get was as a casual reporter for the ABC at Toowong where the afternoon tea came in the best and cleanest crockery I’d encountered anywhere in the world. But, very very strangely, they had no Library.

For a few months I wrote stories and did interviews for TV and radio news … but always with that nagging pressure which all casual workers endure.

Every story I wrote could be my last.

In May 1971 the chief-of-staff called me in and said he was giving me a difficult assignment: “Go up to the Sunshine Coast with a crew and interview the Federal Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam: “If he likes you he’ll call you ‘Comrade’, but he’s on holidays so he won’t be happy to see you: he can be a right irascible bastard.”

Gough had recently announced that he would make an official visit to forbidden “Communist Red China” to meet China’s Premier Zhou Enlai. This had predictably sparked fierce criticism from conservative parties – but, more importantly, from within his own Labor Party.

The visit was becoming a touchy subject: “It’s blowing up to be a big story,” the chief-of-staff said.

Having been in China as a freelancer, writing stories from Canton and Beijing six years earlier (in May 1965) I could understand the controversy.

Even in 1971 Australia still did not recognise the communist government which had taken over China in 1949. Instead, we recognised the small island of Formosa (now Taiwan) off the coast as the real China … which was rather like China insisting on recognising Tasmania but not mainland Australia. Or Hawaii instead of the United States.

So for most Australians from the “better dead than Red” era, Gough was going off to deal with the dreaded enemy. As many saw it, this 54-year-old upstart Sydney lawyer was trying to run government foreign policy from opposition. Not only that, he was taking a party of six top Australian journalists with him to publicise what he was up to.

Gough Whitlam was breaking all the rules after 22 years of non-stop conservative unchanging government in Australia.

Off to See the Whitlam

The cameraman, the sound man and I jumped in an ABC station wagon at Coronation Drive, Toowong, and headed up the Bruce Highway for the Sunshine Coast ... our destination a several-storey motel across the road from the beach.

During the Vietnam War, I had witnessed dozens of gung-ho American TV crews in action, literally running into the midst of battles to get a story before the fighting stopped. But when we pulled up in our station wagon outside the motel and I said “Ok, in we go fellas” … neither of my two ABC colleagues moved.

“No, no, no,” said the cameraman, smiling. “I’m not going in there: Gough’s only going to tell us to piss off.”

“But we’re here to get a story. It’s getting bigger every day.”

“Well, you go in then. If you can get Whitlam to agree to talk on camera then we’ll unload all the gear out of the back of the car.”

I wasn’t fearful at all about going in: I knew from experience that politicians – particularly opposition politicians (since “governments make news; oppositions give only views”) – love to get their faces on TV.

“That last infirmity of noble minds,” Milton called it.

Plus, unknown to the cameraman, I had something up my sleeve: Gough knew my big brother Jack very well. In fact, I think just about everyone in Queensland knew Jack because he’d been a reporter on the state’s only morning paper for 14 years. I relied on Jack’s good standing to get interviews.

My Norwegian girlfriend, who had come to Australia with me, would introduce herself as: “I’m Jack Lunn’s brother’s girlfriend”. And she wasn’t even joking.

Touring with Gough

Jack and Gough were on first name terms because ten years earlier – back in 1961 – as a 22-year-old newly-married Courier-Mail reporter, Jack had toured more than 2,000 miles through Queensland over rutted 1950s roads with Whitlam … who was then Labor’s Deputy Opposition Leader. (This was at a time when an ALP Queensland federal member said: “I never drive between Rockhampton and Mackay without a loaded shotgun on the seat.”)

Whitlam had been delegated the unenviable job of spearheading the Labor Party’s 1961 federal election campaign in anti-Labor Queensland where the party held only three of 18 seats. But Gough’s tour was to prove so successful that in that December election Labor won eight more seats and almost ended the Sir Robert Menzies conservative era. This ensured Gough would eventually lead the Labor Party.

Whitlam’s one-man-one-car 1961 election blitz saw Jack cooped up in a V8 white Ford Customline with a commonwealth driver, Gough, and (for a large part of the trip) Gough’s personal secretary John Menadue. They were headed for Cairns 1,000 miles north, stopping and greeting voters at all points along the way.

First stop was Caboolture just 30 miles north of Brisbane at the famous Butter Factory to meet the workers. The manager offered Gough a taste of a local cheese “Bjelke Blue” – named after a little known conservative Queensland backbencher Joh Bjelke-Petersen, a peanut farmer of Danish ancestry. It was a combination of Danish blue cheese and peanuts. Gough took a dramatic gob-full in front of the workers and then handed the rest back, declaring in his distinctive breathy voice: “I don’t think the coalition will last.”

That night they stayed in Gympie after a Gough rally and next day pushed north. Each night Gough would stop so Jack could find a phone in a public bar somewhere to phone in a story. Being newly-married, Jack was missing his young wife Lyn and would get out more coins to ring home.

Each time when Jack got back in the Customline, Gough would say: “Comrade, how’s the little bride?”

North of Townsville, heading for Cairns and running late, around Innisfail on an eroded section of the Bruce Highway the Customline skidded violently sideways off the furrowed road, blowing two tyres and – with no seat belts in those days – tossing the passengers even closer together than they had already become.

They’d been a week on the road and they hadn’t yet reached Cairns: so, with only one spare tyre, they flagged down a passing car to go for help. Gough, old enough to be Jack’s father, sat with him on the side of the road for a few hours waiting. As was becoming the norm, Gough quoted the Greek and Roman classics, particularly Cicero, while Jack entertained with his penetrating knowledge of Shakespeare and Tennyson and Coleridge and Wordsworth…

When Gough remarked that the positive reception he was getting gave hope for a long-awaited ALP victory in the coming federal election, Jack quoted King Arthur’s words as he was dying (in a Tennyson poem):

The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And God fulfills Himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.

“I can thank Doc Campbell [our English teacher at St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace] for my relationship with Gough,” Jack told me. “If Doc hadn’t made us learn four new lines of poetry or Shakespeare every night I wouldn’t have been in the hunt.”

From Cairns they headed inland through the old gold-mining town of Charters Towers, and then more than 300 miles south down through the guts of Queensland to Emerald: and still they were only a third of the way home.

What a moment when – after two weeks of bad roads – the worse-for-wear Customline limped into the small railway city of Ipswich just west of Brisbane for the final rally. When Jack said Lyn was visiting her family home in Brisbane Street, Ipswich, Gough ordered the driver “head straight for that house”. Jack and Lyn were re-united … while Gough chatted to Lyn’s mother, Molly, on the front verandah.

A Queensland policeman in uniform arrived at the house to welcome the touring party. The policeman was the Labor Party candidate for the seat, Bill Hayden, who (after studying economics at night at the University of Queensland) would 14 years later be named by Gough as his Treasurer.

Gough Gets Angry

Full of confidence, and in my best Singapore tailor-made cream suit, I entered the Boolarong Motel foyer in May 1971 looking forward to meeting my older brother’s travelling comrade.

I asked the man in shorts at reception: “Have you got a Mr Gough Whitlam staying here?”

“You’re a bloody reporter aren’t you?” he said. “I can tell you bastards a mile off.”

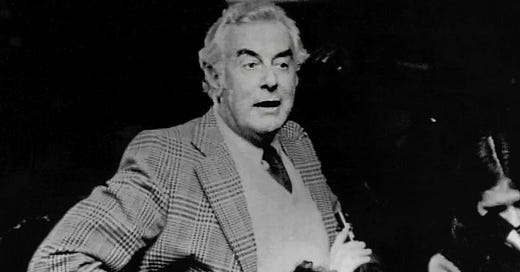

I was fashioning a reply when – bouncing down the stairs at a hundred miles an hour – came the Opposition Leader himself carrying a piece of paper. I’d seen Whitlam in the media but had never met him.

Reporters do what they call “button-hole” people, so I leapt in front of Gough before he could escape and was surprised how tall he was: “Mr Whitlam … I’m Hugh Lunn, from the ABC in Brisbane, and I’ve been sent up here to interview you about your upcoming trip to China to meet Premier Zhou Enlai…” (I was actually dying to tell him I’d beaten him into China by 6 years, but thought better of it.)

To my surprise, Gough became angry.

“I’m up here on holiday!” he said loudly. “How much did it cost the ABC to send you and a crew up here to interview me? Who was it that sent you? The ABC will hear about this – it’s always complaining about a lack of funds and now they’re wasting money like this.” And my brother’s friend brushed past me.

Obviously Gough couldn’t see the family resemblance.

I followed him sheepishly out onto the street where the cameraman and soundman were leaning on the station wagon nodding “I told you so” and laughing. They knew that a man such as Gough didn’t care whether he was on TV or not. Whereas I was accustomed to politicians around the world wanting to ingratiate themselves with reporters.

I’d interviewed Richard Nixon, Vice President Spiro Agnew, President Marcos, President Thieu, Premier Nguyen Cao Ky, President Suharto, Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik…

Whereas this Gough Whitlam was different. But now, so was Australia.

The following year, 1972, Gough’s eloquence, and some would say his arrogance, saw him sweep to power as Prime Minister of Australia.

The next time I saw Gough up close was when he arrived in, of all places, the small bayside Brisbane suburb of Sandgate where you have to drive around a small lake to get there.

I was there as a reporter for The Australian. The party faithful were waiting in the hall to see their new Prime Minister and the speech writer handed Gough his speech … which Gough threw into a waste paper bin with a flourish before leaning back against the wall, beer in hand, and addressed the true believers in his Whitlam way: “It’s so nice to be on the other side of the pond.”

The hall erupted.

A few months later I cadged a lift on the state government plane being flown to Canberra by now Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen and his pilot Beryl Young for the Premiers’ Conference chaired by Prime Minister Whitlam. It was Bjelke-Petersen’s first visit to Canberra under a Labor government and on the plane Joh said: “Gough Whitlam has so much charm that I have to be careful not to be taken in by him.”

Gough greeted the Queensland party as I stood back taking notes. He seemed amused by Joh’s group. One of the Queenslanders was Sir Charles Barton whom Joh introduced to Gough saying, “and this is our State Co-ordinator-General”. As Gough shook Barton’s hand he remarked, “State Co-ordinator-General! What a wonderful title.” Turning to Joh he added: “Co-ordinator-General! I must get myself one of those!”

Whitlam asked Joh to sit down, motioning to the chair on his right, saying: “I would not wish to put you, Premier, in the wrong position.”

After the Premiers’ Conference, Gough invited all the premiers to The Lodge (his official home) for a drink and turned specifically to Joh: “And that includes pineapple juice for you Joh, and me.” Bjelke-Petersen declined, telling Whitlam he had another appointment. It transpired the other appointment was that Joh wanted me to write where Queensland tax money ended up: so he took me in his chauffeur-driven car around Canberra pointing out the smooth black ribbon roads and the huge mansions. He seemed to know where they all were.

“Jack, Jack, Jack!”

It turned out that things were not going well for Gough in government as his cabinet ministers tumbled over themselves to get into trouble, and the media increasingly criticised his policies for “going too far”. But Whitlam was not one to back down and – though it was a great line – I saw him unnecessarily frighten a dinner of conservative businessmen in Brisbane by saying from the podium: “When I look at the powers available to me as Prime Minister, I stand, like Robert Clive, astounded at my own moderation.”

My brother Jack and I often covered the same events for our different newspapers.

One of these was a 1974 Queensland mining industry dinner in Brisbane addressed by Gough. As I sat at a table with a dozen mining people, none had a good word to say about him. But, after Gough spoke, the woman opposite said: “Billy Snedden [the Liberal Opposition Leader] is going to have to grow five inches to get my vote now.”

Whitlam was seated with the official party on a stage above the many, many rows of tables. Jack stood up to phone through his story and made his way behind the hundreds to the exit. Suddenly Gough rose up and began waving and shouting across all the heads: “Jack. Jack. Jack…!” and everyone wondered what the hell was going on. Jack later explained: “Gough just wanted to ask me how Lyn and the kids are doing.”

Camping Out in Sydney

Jack and Gough had stayed in touch since that epic 1961 car trek through Queensland.

Gough had said “if you’re ever in Sydney come and see me”. So the next year, in 1962, Jack and Lyn headed south on a camping holiday in their Wolseley 1500.

The Lunn family had always holidayed in tents, so Jack packed the family 9x7-foot lean-to in the boot and he and Lyn set up camp in Sydney’s Narrabeen camping ground on the glorious northern beaches. The camp only had an outdoor cold water shower with walls … but no roof.

Gough invited them to lunch with him at a restaurant in Martin Place. Always prepared and effortlessly fashionable, Lyn had packed a lovely royal blue dress with white spots.

“And where are you staying in Sydney?” Whitlam asked the young couple.

Jack was about to say they were staying in a tent in a camping ground when Lyn jumped in: “Oh, we’re staying on the North Shore, Gough.”

The friendship didn’t end there. A few years later when Gough was in Brisbane, he invited them over to Kangaroo Point Lodge for breakfast – and was so relaxed that he greeted them while wearing a pair of shortie pyjamas.

Dinner with Gough

Gough Whitlam had won two national elections in three years by 1975 but it wasn’t enough. Everyone was criticising him for being consumed by the classics and not taking an interest in economic affairs.

And that was true.

Brisbane reporter Quentin Dempster told me that he was in a car travelling to Rockhampton with Whitlam sitting in the front seat and Bill Hayden in the back. The fidgety Hayden was reading out from a thick pile of papers various facts Gough should know about this important central Queensland city: but Gough wasn’t paying attention.

Finally, Hayden got excited and shouted above the noise of the car: “Gough! Gough! Listen to this! It says here that there are more beef cattle within 200 miles of Rockhampton than anywhere else in the world!”

Whitlam turned his head around and slowly said: “Faaaaark!”

After being sacked by the Queen’s representative, the Governor-General, Whitlam was forced to a third election in three years (as if three times proves it) and finally lost. But instead of taking his bat and going home as expected, he stayed on as Opposition Leader.

I visited Canberra in 1977 and dropped in on my local member, former Queensland Liberal president, John Moore, a very talented tennis player.

John’s desk was covered in a huge pile of junk mail and he said: “I’ll show you what’s going on down here” and he swept the lot into a rubbish bin with a dramatic sweep of one arm. Then he unexpectedly threw a directory list of all the members of parliament across the desk and said: “Who would you like to have dinner with tonight?”

I looked down the long list, including Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, and, although I was dealing with a Liberal, said: “The only one I would be interested in having dinner with is Gough Whitlam.”

Moore picked up his phone and said: “Gough, I’ve got Hugh Lunn in my office and he says you’re the only member he would like to have dinner with tonight.”

John Moore couldn’t get a pairing, so now that I was “Jack Lunn’s brother” I had a one-on-one chat with Gough who asked about Jack and Lyn and even knew the names of their three children – and then told me what a great bloke John Moore was. Gough was best friends with another Queensland Liberal MP, Jim Killen, who was almost as good a speaker as Whitlam himself. I concluded that politics in Canberra is a funny business … depending as much on personal friendships as on party loyalties. Lord knows, Gough ended up close friends with Malcolm Fraser: the Liberal who turfed him out with the aid of the Governor-General.

I asked Gough that night about his sacking, saying that, although he personally ensured Australia recognised China and extricated Australia from the Vietnam War while terminating military conscription … at the same time as pushing through no-fault divorce … maybe, just maybe, he would have been smarter not to go breaking all the rules at once.

“As George Orwell wrote,” Gough said, ‘the weak in a world governed by the strong must break the rules, or perish.”

Imperious Gough

While successfully introducing such longed-for policies, Gough’s personality did not help his cause by laying himself open to accusations of being imperious, haughty, and the oft-quoted “too smart by half”.

At a Brisbane press club lunch before the 1974 election Gough criticised Bjelke-Petersen for his many biting criticisms of the Whitlam government. But instead of saying Joh’s statements were being put in his mouth by his brilliant press officer Allen Callaghan, Gough made a Biblical reference that meant a lot only to him: “I suppose you can see the hand of Jacob in the paw of Esau.”

Many times people didn’t realise that Gough was speaking with tongue firmly in cheek.

The popular ALP Senator Ron McAuliffe, also president of the Queensland Rugby League, told me that he arranged for Prime Minister Whitlam to greet the players in the centre of an over-flowing Lang Park in Brisbane before kick-off in an Australia v. New Zealand rugby league Test match.

But when Gough and Ron reached the centre and the Prime Minister’s presence was announced, the crowd began a crescendo of boos and catcalls. “It was so bad I had to get Gough out of there quickly,” the loveable Ron said, “so I ushered him straight to the sideline. When we got there, Gough turned to me and said: ‘Ron, had I known how unpopular you were up here I would never have gone out there with you’.”

Your Excellency

A decade after losing the Prime Ministership, Gough launched his new book at the National Press Club in November 1985 and I was sent down to Canberra to cover the event for The Australian.

The Press Club was packed out with an audience that included ambassadors from scores of countries around the world – now, of course, including China. Ambassadors are so high-ranking that protocol demands they be addressed as “your excellency”.

Gough brought the house down when he stood up and began his speech: “Fellow Excellencies…”

Years later . . .

With Jack now Editor-in-Chief of The Courier-Mail and Sunday Mail, he and Lyn are standing talking to Whitlam before a celebratory dinner at the Hilton in Brisbane. Gough has just opened a huge exhibition of French paintings at the Queensland Art Gallery.

An official, anxious for proceedings to start, urges Gough to take his seat.

Gough ignores him completely and keeps talking to the Lunns.

Ten minutes later, the official returns. He tugs at Gough’s sleeve: “Mr Whitlam, Mr Whitlam, proceedings are starting now!”

Gough pulls his arm away without a glance and continues to chat about old times.

Finally, the Curator of the French exhibition arrives: “Mr Whitlam, I have to inform you that you are on Table One!”

Gough turns unhurriedly towards him, saying: “Naturally”.

Thanks for confirming the shotgun story Bob. I'm sure people in Syd-Melb-Canberra will think I'm making things up.

Happy New Year,

Hugh

Yes Joan, there are no Whitlams or Killens around today -- and maybe there won't be again.