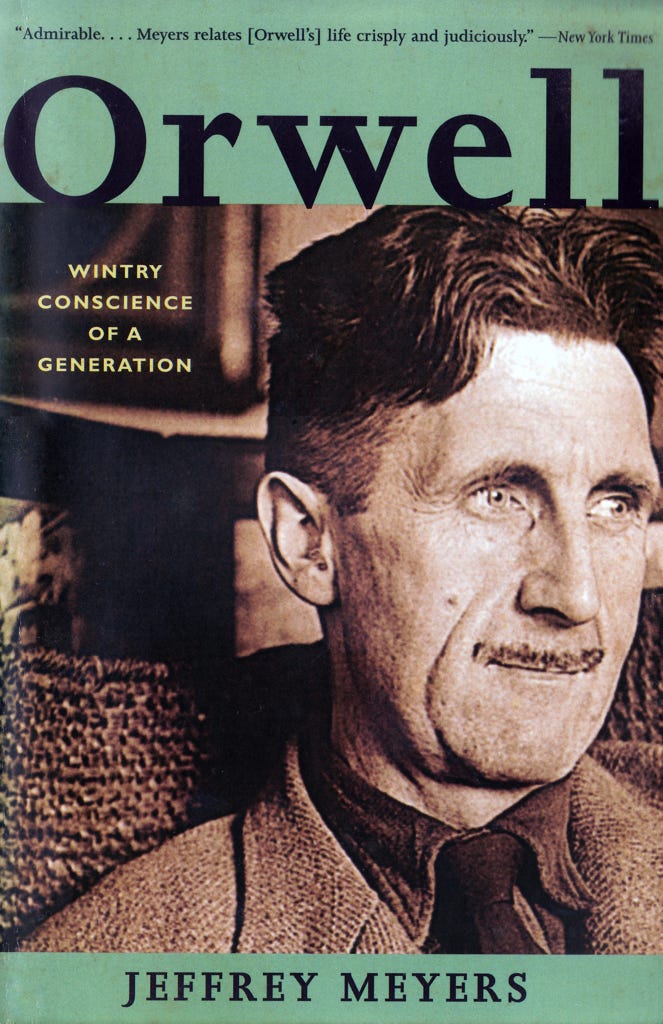

My favourite writer has been, and will always be, George Orwell: because of his clarity.

As he himself wrote, he aimed to make his writing “as clear as a pane of glass”.

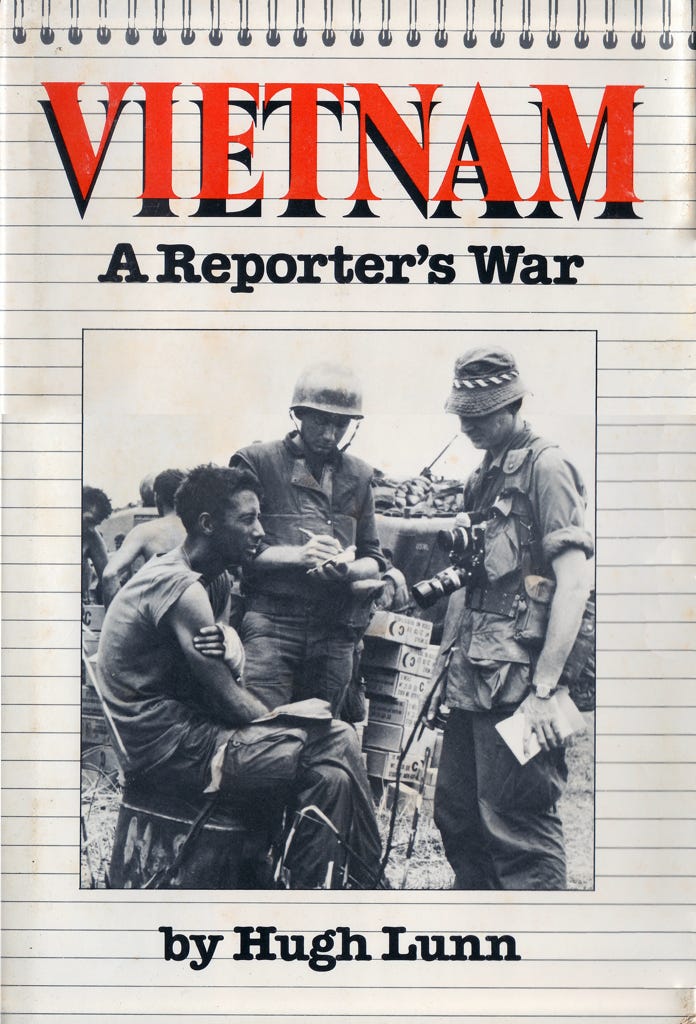

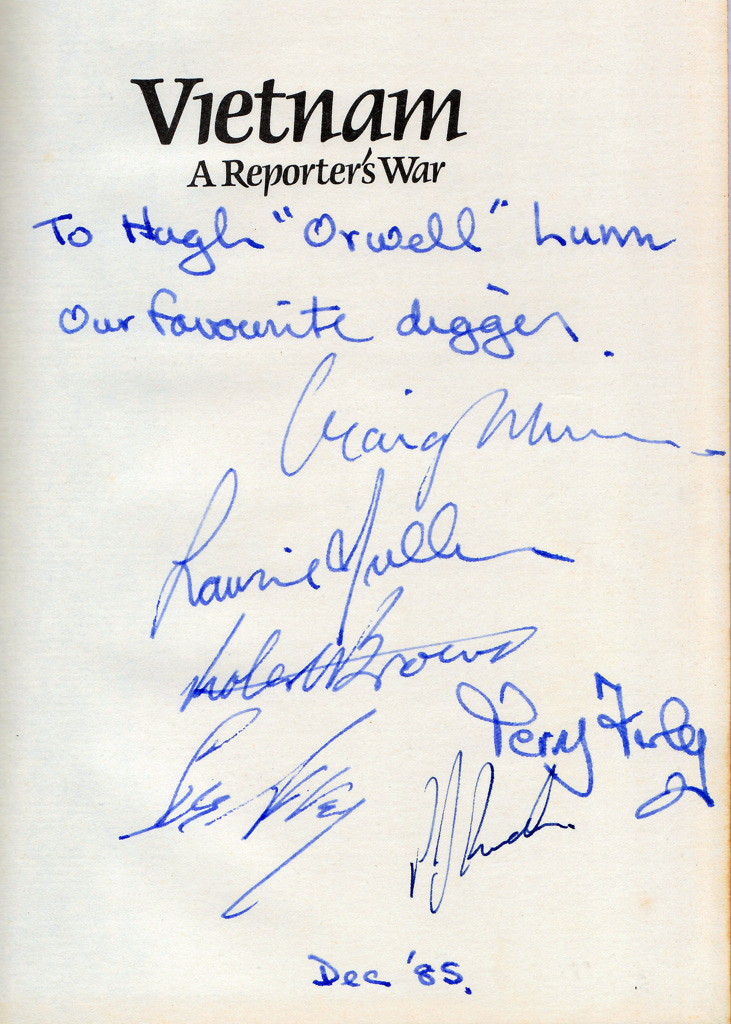

I turned to Orwell many years ago when I wanted to get my first book VIETNAM: A Reporter’s War published.

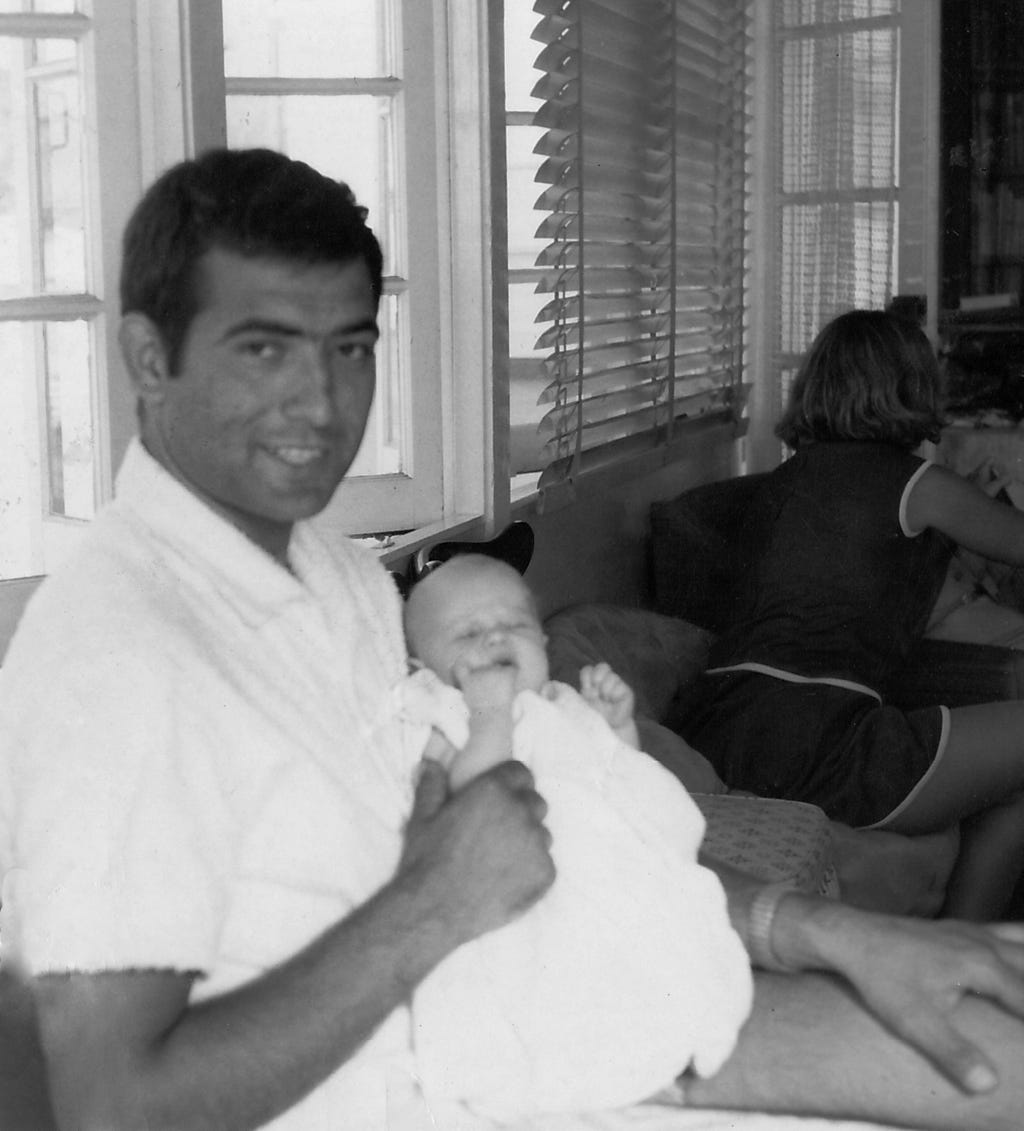

Home on leave from Reuters as a 27-year-old in 1968, I complained to my old classmate Jim Egoroff that I kept meeting people in Brisbane who felt they knew all about that War.

As Orwell wrote: “the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled”.

I told Jim that I had seen so much “I could write a book about it”.

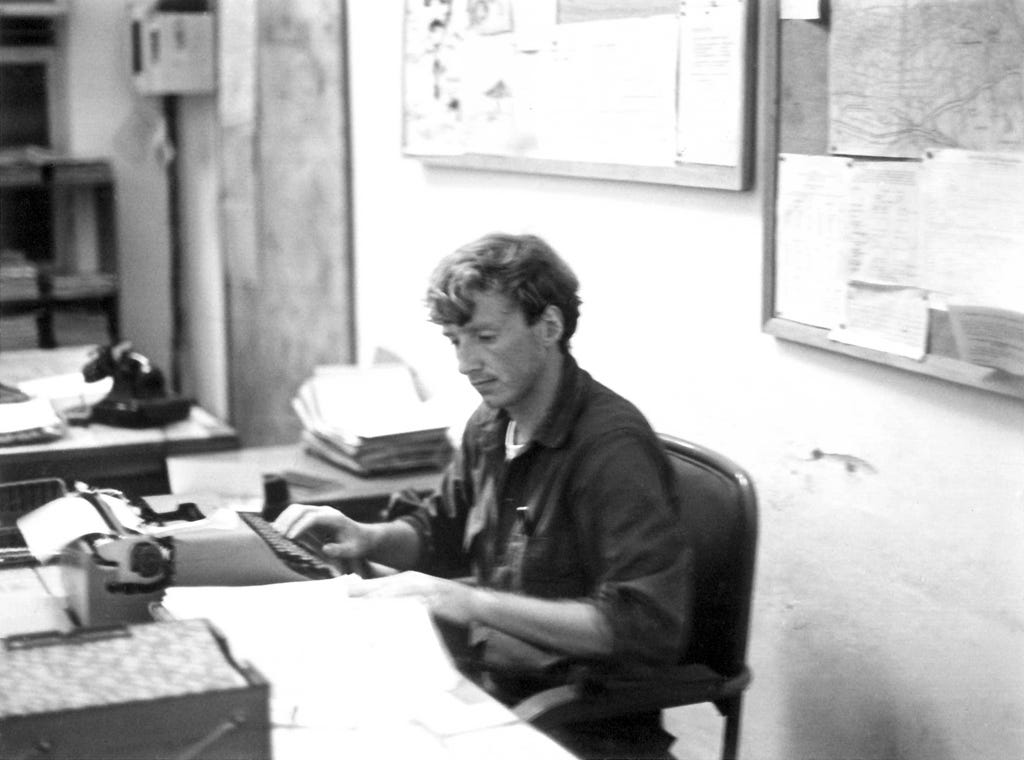

Taking me literally, the Russian turns up driving a utility and unloads a desk, a chair, a typewriter, carbon paper, white-out, spare ribbons, and a ream of typing paper.

“You bastard boy Lunn, you said you could write a book: write it!”

I’d never written a book before, but I bashed out a short manuscript (making six carbon copies). The facts, the spelling, the names, the battles, were all correct … but it was such a mishmash that six publishers out of six rejected it.

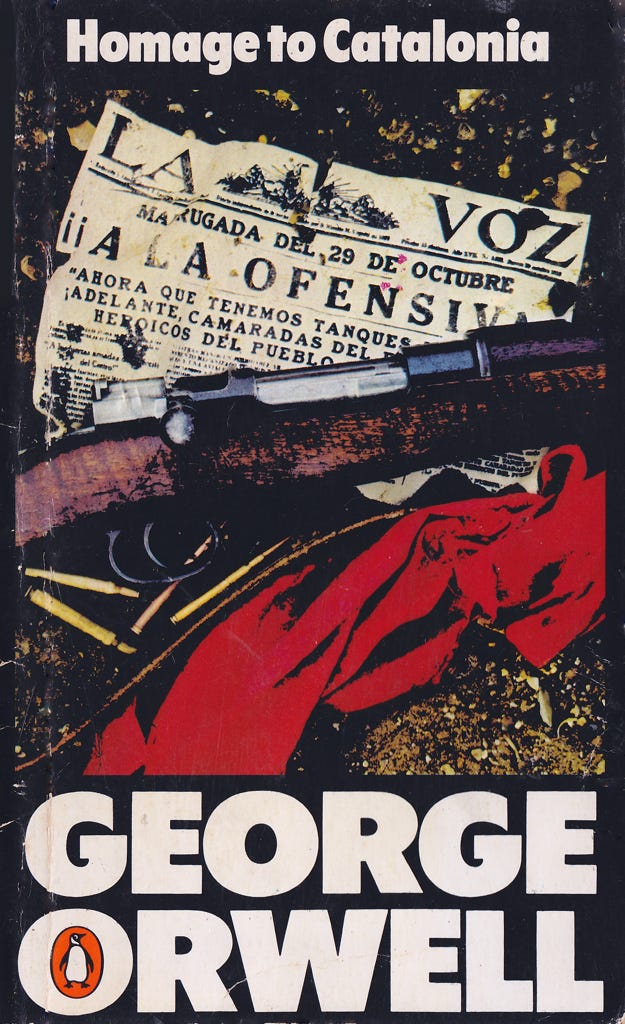

Then I read Orwell’s memoir of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War exactly 30 years earlier, Homage to Catalonia.

I took to heart Orwell’s warning that war books written from a political angle are “shockingly dull” because “they tell you what to think”. Whereas great war books such as A Farewell to Arms and All Quiet on the Western Front, were written “not by propagandists, but by victims”.

That was definitely me.

Reading Orwell I could see that you didn’t have to have the world’s greatest story. You just had to type out truthfully what happened to you … so that people who weren’t there would feel what it was like.

Written in your own sincere voice.

However, Orwell warned that adopting such a straight voice required the author to reveal much more of himself than he might desire.

Or as Orwell put it:

An autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.

A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, because every life viewed from the inside would be a series of defeats.

So – 17 years after my first attempt – I pulled out the sixth carbon copy of that aging manuscript and rewrote it … this time revealing just how frightened I’d been when bombed, when shot at, and when isolated.

Then there was the longest night of my war.

With 200 Marines I was creeping through the rice paddies in the dark under fire.

We were in the Hiep Duc Valley which the Americans had declared “a Free Fire Zone” — where everyone was presumed an enemy.

In the original manuscript I recorded the details of the battle: but now (Orwell-like) I slowed down the writing to describe what was around us. Just like him, I speculated about the peasants who normally farmed the rice paddies... and what they might think now.

Could they hear the screams of the horribly wounded Marines?

As Orwell would have demanded, I also detailed the terrible miscalculation I made on the night of the biggest story of the entire15-year Vietnam War.

I was having a shower at my English girlfriend’s flat in the Saigon suburbs when – for the first time in history – the Viet Cong invaded Saigon.

While I was towelling down, the mortars and the rockets started landing and VC guerillas stormed the Presidential Palace and breached the walls of Pentagon East (the American Embassy).

This new manuscript found a publisher, won an award, was set in Australian high schools in two states, was twice published in New York, and is still in print today.

I thought I’d got away with my Orwell impersonation … until famous Sydney screenwriter Moya Wood sent a long hand-written letter to say how much my Vietnam book reminded her of Homage to Catalonia.

The book’s first publisher, University of Queensland Press (UQP), presented me with a signed hardback leather-bound edition.

In Orwell’s essay on his early school years Such, Such Were the Joys he said he aimed to “mock the myth of childhood joy unbounded”.

As he truly wrote: “Childhood has its pathetic side and also its nightmare side. A child lives a lot of its time in a terrifying world.”

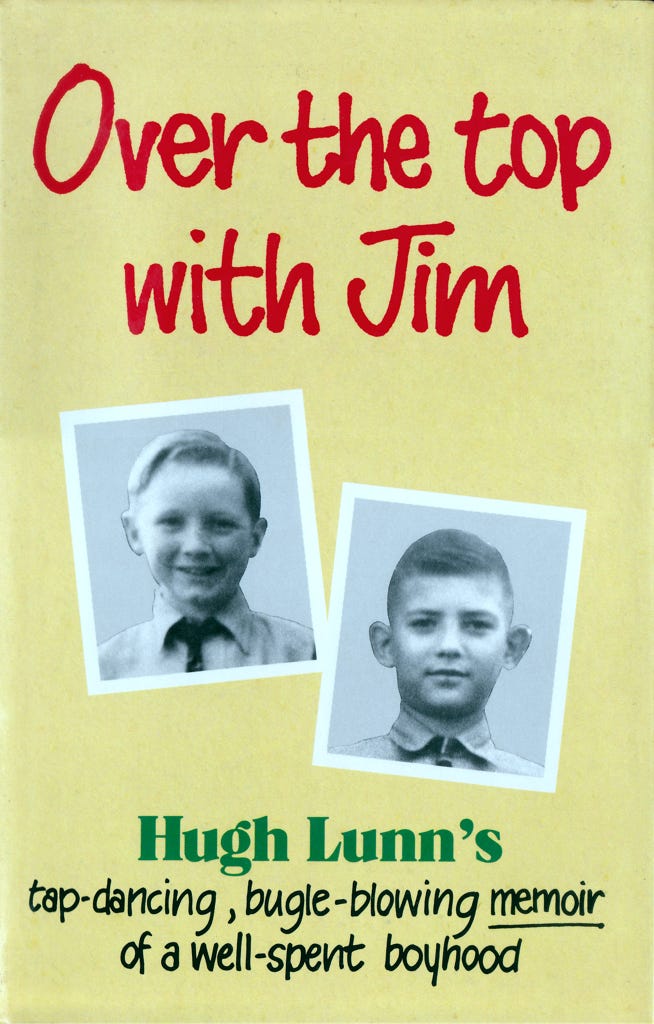

I thought the same, and so when it came to writing my childhood memoir three years after the Vietnam book came out, the first thing I typed was a title: A Child’s War.

This revealed my intention … to show that childhood was not the happy, innocent time everyone said. (But when it was eventually published readers said “what a happy, innocent childhood”.)

Orwell praised Henry Miller and James Joyce for their “willingness to mention the inane, squalid facts of everyday life”, so I marched fearlessly into telling the truth no matter how disgraceful: worms and all.

How, when I started school at Mary Immaculate Convent in Brisbane in 1945, I couldn’t write the figure 2: I kept swinging my slate pencil around to the left instead of to the right.

How I couldn’t pronounce the word “three” and always ended up saying “tree”.

How I was jealous of my perfect blonde little sister Gay who, in every situation, was always the centre of attention.

Plus, I could never match Big Brother Jackie.

Long division and analysing sentences were a mystery … so much so that Sister Vincent refused to nominate me for the State Scholarship Public Examination: the exam to decide which students were smart enough to go on to secondary school.

“I’ve never had a failure in State Scholarship,” Sister Vincent explained when I slumped in front of her.

She didn’t want me ruining her unblemished record.

So I had to nominate myself, aged 13.

Of course, I did pass 1954 State Scholarship and go onto secondary school … otherwise you wouldn’t have this story to read, or my books. But Orwell would have insisted I reveal that I passed by one mark out of 400.

Passing English was compulsory … even if, like me, you didn’t understand how to parse words.

It was pre-decimal days, so the English exam was marked out of 150.

I scored 76.

No wonder then that — when the book was published as Over the Top with Jim in 1989 — a former Prefect from my high school asked: “Were you depressed when you wrote that book?” And a reviewer in a South Australian teachers’ magazine wrote: “Hugh Lunn was in need of remedial teaching”.

They had missed George Orwell’s point: people aren’t interested in hearing others praising themselves – they hear and see that every day of the week.

Orwell also criticised writers who tell you what you ought to feel … instead of making you feel it.

Bearing this in mind, I didn’t write “Jim Egoroff was tough”. Instead, I told how he came to school one day with a black eye and, when I asked “Who gave you that black eye, Jim?” he replied:

Nobody gave it to me, Lunn, you bastard boy, I had to fight for it.

And that is how a Russian became the main character in my childhood story, something no other Australian memoir had.

Even though Jim wasn’t the main character in my real childhood.

Three different publishers warned me not to write a book on my childhood.

They said “books on Australian childhoods don’t sell”; “everyone writes a book about their childhood”; and “no one cares about your childhood”.

But Orwell admired any book “which opens up a new world not by revealing what is strange, but by revealing what is familiar”.

What if I could capture an Australia that had disappeared, but was still familiar?

So, when I sat down to write Over the Top with Jim, I made a list of what it was like to be a kid in Australia in the 1950s.

We worried about Protestants versus Catholics, Russian nuclear bombs and satellites, Chinese Communist expansion … so much so that 13-year-old schoolboys had to join the Army, the Air Force, or the Sea cadets.

We were taught how to fire a .303 rifle, an automatic Bren gun, a Vicker’s machine gun … and, in Jim’s case, how to fire mortar bombs off into the distance.

Even the nuns had warned us about the Red Peril (Russia) that would one day sweep down upon us with the Yellow Peril (Red China).

For a few weeks I struggled to start my book.

How to capture all of this?

Then it came to me.

To write truly – as Orwell demanded – I found I had to write the book in the child’s voice.

Jim, the 9-year-old Russian boy whose family has escaped Red China after Mao’s 1949 revolution, marches stiffly into my Convent class in his Russky military school uniform, smelling of garlic.

Only the child could say: “He had a funny name the like of which we Australians had never heard before: Dimitri Egoroff.”

And guess who was the unfortunate boy who had to sit next to this black-haired Russian with arms like a mud crab — and a wide scar down the middle of his nose?

The nun reassured me he was a “White” Russian.

Well, he didn’t look very white to this 9-year-old who asked guilelessly: What about the White Australia Policy where people were supposed to be white before they could get in?

So the child did his disgraceful duty.

“You Communist pig, Dima”, I sneered from behind him, shortening Dimitri because it was long, as was our custom … Convinced that he was too scared to answer I continued: “You Russian dog, Dima.”

Multi-culturalism had arrived in Australia … and I was resisting it.

Just as I was about to give the Russian another one, Egoroff turned around: “You Australian donkey,” he said, in English … “I rubber your ears! I rubber your ears!” and lunged his palms at both sides of my head.

It was torture, Japanese torture at its worst … If ever an example of Red Aggression was needed, this was it: the Cold War they talked about all the time in Dad’s cake shop was really starting to hot up.

What they said on the wireless all the time was so right: there was no place to hide from Communism!

George Orwell, who once wrote “wars are not won without fighting” would have cheered my act of revenge against the Russian.

I reached for my sharp lead pencil and stabbed him in the thigh.

As punishment, instead of being caned, I had to sit next to Egoroff in class every day for the rest of our time at the Convent, like his Guardian Angel … so that I could help him adapt to our Australian way of life.

I bet the nuns didn’t know that we would end up helping each other cheat.

As Orwell wrote in Such, Such Were the Joys (referring to canings), “I was in a world where it was not possible for me to be good”.

Facing huge class sizes, the nuns invariably got pupils to correct the work of the person sitting next to them. So Jim and I would leave spaces instead of wrong answers – so we could write in the correct answer before giving each other a big tick.

Mind you, we did have morals: we didn’t cheat to beat the other kids … just to make sure we got 3 out of 10 correct.

Any less than that, and we’d get the cane.

Any more, and they’d know we’d been cheating.

Thus did Jim and me end up lifelong friends … always endeavouring (though rarely succeeding) to correct each other’s mistakes before they happened.

George Orwell had trouble getting his early books published in London because of a shortage of paper caused by World War II.

So I didn’t panic when several publishers rejected my childhood memoir without wanting to read it ... despite Australia having plenty of paper in 1989.

Even UQP – which had already published four of my books – warned me against writing it. But, give Publishing Manager Dr Craig Munro his due, he said that, as a friend, he would be willing to cast an eye over the first three chapters.

I gave him the first 11 chapters on a floppy disk and next day he burst into my Taringa Queenslander saying “more Jim!”

Orwell once observed that there is no argument needed to defend a piece of writing: “it defends itself by surviving”.

Despite all those early publisher predictions, Over the Top with Jim is still in print today with HarperCollins: 35 years after it was first published.

Still, what would George Orwell have made of the book?

I suspect he would have strongly agreed with my decision to write it as the child.

After all, George once scribbled a note saying: “One cannot really be Catholic and grown up.”

Several people have mentioned Anna Funder's book Wifedom.

I read it two years ago and two things struck me:

1. she is a superior writer.

2.she does her best to ruin Orwell's reputation. Which in itself is fine -- but she draws hard conclusions from hearsay, something which would not be allowed in a court -- thus using the word "perhaps" a lot.

Ironic that she uses "Mrs Orwell" on the cover, which Eileen never did.

But then a book about "Ms O'Shaughnessy" would hardly attract worldwide attention.

I received a nice comment on this by email: "It’s astonishingly clear and informative and exciting to read like a confessional or an inside scoop."

Makes my heart glad. Hugh