At the age of 13, I was shanghaied into the Australian Army Cadet Corp a few days after arriving at secondary school in 1955.

I say “shanghaied”, because I was given no choice: the cadets were compulsory at St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace, Brisbane … unless you were medically unfit.

It was like I’d died and gone to Purgatory after nine years under the nuns at Mary Immaculate Convent, Annerley.

The only War back there was with the State School Kids.

Now, suddenly, I was in Grade 9 (sub-junior) on the other side of the city dressed up like a World War II soldier.

When we’d arrived at the Kelvin Grove Army Depot Q-Store, a soldier threw me a khaki uniform across the wide counter.

The trousers were way too big, so I complained: “These trousers say they’re for someone 5 foot 10 inches tall. I’m only 5 foot three.”

“You’re growing like a horse … Next!” he barked.

So I found myself in an ill-fitting khaki uniform, heavy black boots, a khaki army belt and gaiters, a .303 rifle … and a brown slouch hat with an upturned lefthand side.

(The upturned brim was so you didn’t knock your hat off with your rifle when you shouldered arms.)

Possibly because I was a Convent boy – and therefore assumed to have been cosseted – I was assigned to 9-Platoon.

I soon worked out that this infantry platoon was the bottom one in the whole school … there was no 10-Platoon. Above the infantry platoons there were others like Mortar, Machine-Gun, Intelligence, and Q-Store.

At least I only had to wear that shapeless uniform through Annerley and the city on Mondays when cadets trained after school.

In school, I’d been relegated to the C Class for the dumb, the foreign, and the unruly. Coincidentally, I’d also been picked in the bottom Rugby team … the ninth-best Under-15 team, the Is.

There was no Under-15 Js.

So, when I thought about it, the whole School was above me at this famous GPS Christian Brothers Catholic College – where, when not in khaki, we wore suits, ties, and broad-brimmed felt hats.

Looming over me were all the A-Class kids and the B-Class kids … plus eight Platoons of sub-juniors … and all the older cadets: including the Lance Corporals, the Corporals, the Sergeants, and the 15 Under Officers.

Under Officers were grade 12 schoolboys wearing Officer uniforms who had to be saluted at all times.

Above them were some of our teachers: Christian Brothers who wore military uniforms too: a Major, a Captain, and a couple of Lieutenants.

Of course, also above me were eight Under-15 Rugby teams.

And soon there were nine.

(I was dropped from the Under-15 Is after just one match.)

The schoolwork was much harder here too: as well as Physics and Chemistry and Shakespeare and Trigonometry (nothing to do with shooting your .303 I was told) we had to learn Latin … a language that went out with Roman soldiers.

No one in Annerley could speak Latin, so with no help at home I couldn’t pass any Latin exam: which meant “the cuts” from a thick, stitched, stained leather strap.

On both hands.

As the blows struck, I recited under my breath:

Latin is a dead language

Dead as dead can be;

It killed off all the Romans ...

And now it’s killing me!

Not only was I in trouble with the teachers, but during that first winter of 1955 I got into big strife with the Army.

It happened on the annual 10-day training camp where we lived in tents out in the bush miles from anywhere at a place called Greenbank.

We were only issued five blankets each – plus a hessian bag we were told to fill with straw, for a mattress.

So, even though there were four boys to a tent, we all froze.

In the morning, we had to make our “bed” in a certain complicated way and clean the tent. Then all brass had to be cleaned and polished spotless despite the dusty surrounds.

A team of Under Officers inspected each tent and awarded marks.

Being an owl, not a fowl, I could never get everything done in time for inspection and ended up having to run around one of the dirt parade grounds carrying my .303 rifle above my head as punishment.

With 325 cadets each in charge of his own World War I rifle, we were told to hide the bolt in our tent so no thief could get away with a usable .303.

We were taught how to load the magazine with seven bullets. It could fire only one shot at a time, but this was justified by the Army saying: “The only good shot is an aimed one”.

We were shown how to clean the rifled barrel (which spun the bullet for accuracy and distance) with oil, using the felt-ended pull-through kept in the butt.

Things really went downhill the day we marched miles to the rifle range carrying our heavy .303s.

We lined up in groups of 10 behind the shooting mound and, being in 9-Platoon, I was in the last group … just like in the queues for meals.

On the mound, a regular Army soldier paraded around behind us waving a baton shouting: “REMEMBER! YOU’LL ALL BE FIGHTING FOR THIS LAND YOU’RE STANDING ON IN A COUPLE OF YEARS!”

If you turned around to look at him, he’d shout: “DON’T TURN AROUND! It’s a good way to shoot half-a-dozen of your mates!”

Then he shouted “LIMBER UP!” – which in Army language meant: jump forward to the ground with your rifle landing on the sandbag in front and point it towards the targets 300 yards away.

You scored if you hit the black bullseye or an “inner” – the next circle out.

Though I was only 13, this was the part I was looking forward to.

My big brother Jackie and I – in addition to our knife-throwing and bow and arrow skills – shared a Daisy Air Rifle at home and were good shots. But just as I lined up the two sights with the bullseye and squeezed “first pressure” on the .303 trigger, the boy next to me fired.

Hot oil hit me in the face. My ears rang. It was like a bomb had gone off.

I did get two large shiny bullets into the distant target, but, when I pulled the trigger for a third shot … nothing happened!

Grandpa Duncan had told us how his gun had once exploded in his face down in the Numinbah Valley behind the Gold Coast … so I hoicked my .303 over the front of the mound, down into the scrub.

Although I was only protecting everyone from an explosion, the Army regular had a fit.

He stopped all firing and ordered me off the mound and off the rifle range … I had to march back to base alone without being given a chance to show I could shoot straight.

The whole world had arrived on top of me: and it didn’t like me.

There seemed to be no way out from underneath.

No one could help me here.

My big brother Jackie wasn’t in the cadets because he’d had rheumatic fever; my father Fred was busy making pies in his cake shop to pay our school fees; and my mother Olive would never accept any sentence that contained the phrase “I can’t”.

Every time I used it, Olive would respond:

I can’t is a mean little coward

A boy that is half a man;

Set on him a wee little doggie

For the world knows, and honours, “I can”.

On the second day at cadet camp, I noticed that one small group of boys led a rather pleasant, sheltered life.

These cadets were allowed to stand out from the crowd, and held meetings in their own large tent.

They didn’t carry rifles.

Instead, they were armed with shiny musical instruments – trumpets, cornets, bugles, a trombone … and kettle drums, tenor drums, and a huge base drum.

That’s why they needed the big tent.

And what’s more … they weren’t slouching around in ugly oversize uniforms. They wore glamorous white webbing and gaiters, white epaulettes … one bicep decorated with a cute little brass bugle or a drum; the other a green felt-backed lyre.

Plus they wore a red-and-black sash diagonally across the chest.

Imagine marching through town and Annerley Junction and sitting in the C Class dressed like that!

So I determined to join the boys in the Band.

The only trouble was, I couldn’t drum or play a trumpet.

The only musical instrument at Mary Immaculate Convent had been a piano.

Gathering up all my courage, I stepped into the circus tent and approached the Sergeant in charge of the Band … a handsome older boy with a tanned face, perfect bright white teeth, and three stripes on his arm.

I had noticed that – while we all looked scruffy and unslept – he was always clean and pressed … as if he’d just stepped out of a dry-cleaning shop.

His name was Brian Buggy.

Sergeant Buggy, who was a swimming champion, had no reason to bother with a 9-Platoon private wearing a uniform made for someone else. But, for the first time in high school, someone gave me a civil reception.

He called me “Hugh” and invited me to sit down.

Straight away I was heartened. He seemed to open up possibilities … life was not going to be bad all the time.

When I said I’d like to join his band as a trumpeter, he asked how long I’d been playing.

Err… not yet, I said.

Had I approached the Major, or my Under Officer, or my Platoon Sergeant to tell them?

They wouldn’t take any notice of me if I did.

Why did I want to join?

Because I thought I’d be a good trumpeter: it was what I wanted to do. I liked the sound the trumpet made and the shiny aesthetic look.

Sergeant Buggy could have kicked me out there and then, but he flashed his whites and explained that there were no spare trumpets or cornets available.

They’d all been allocated a year ago.

I must have slumped visibly because he then said:

“I’ll tell you what Hugh. We have three old brass bugles left over from before all the cornets arrived. If you’re that keen, I’ll lend you a bugle to practise on. The first thing a trumpeter needs to do is harden his lip so he can hit the high notes.”

Sergeant Buggy also explained that the movement of the tongue had to be spot-on to play the correct notes and create effects.

“To get your tongue trumpet-ready, Hugh, keep saying to yourself over and over, whenever you think of it … tick-a-tee, tick-a-tee, tick-a tee.

“And when you can play Come to the Cookhouse Door Boys on that bugle, I promise I’ll have another look at you.”

I hit the ground running with that old brass bugle – though, when I did blow Come to the Cookhouse Door Boys , I accidentally sent 325 Terrace cadets rushing off the parade ground under the nose of the Major for an early lunch.

So I had to clean the latrines.

Sergeant Buggy came to see me: “The positive thing, Hugh, is, that everyone recognised which tune you were playing. Well done!”

To avoid getting into trouble again, he suggested I practise quietly by taking the mouthpiece out of the bugle and blowing it … that way no one would hear me.

“When you’re good enough you can play a tune just on the mouthpiece,” Buggy said, and he removed my mouthpiece – which fitted neatly into the palm of his right hand – and played a tune.

Then he showed how you could play the bugle softly by stuffing your free hand in the end to muffle the sound.

It turned out that Sergeant Buggy had created this special Band by cajoling the Brothers – who lived a vow of poverty – into buying cornets to replace all the old bugles.

He wanted the cornets to take the piercing edge off the several trumpets and thus provide a warmer overall sound.

As the Terrace Magazine proudly boasted at the end of that year: “The Band has been equipped with cornets which have greatly added to the appeal. A varied repertoire of marching tunes has thus been accomplished in a short time, due to the untiring zeal of Sergeant Brian Buggy.”

Terrace had thus formed the only all-cornet/trumpet cadet band in Brisbane.

Other schools now asked Buggy’s Band to play for them on their special occasions.

Most schools had all-bugle bands, but a bugle can only play five notes. So their bands could only play “calls” like The Last Post, Reville (to wake everyone at dawn), and the Intro to “Dog Faced Soldier”.

Whereas Brian Buggy’s Band could now play Dog Faced Soldier beginning to end: plus lots of other popular numbers like Waltzing Matilda, Toledo, Mocking Bird Hill, Carnival of Venice, Stars and Stripes, Colonel Bogey, It’s a Long Way to Tipperary, Pack Up Your Troubles, Bridge on the River Kwai…

Even very difficult hymns like Nearer My God to Thee.

Inside his tent, Sergeant Buggy would even lead his Band in Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood” and the poles would be rocking.

For “lights out” at the end of the day in camp at 9 pm, the usual single bugler wasn’t enough for Buggy. He would organize three Band members to position themselves at different places around the camp, and answer each other’s call.

In bed, in a tent, in the dark, in the bush, away from home and all that you held dear … it was both haunting and reassuring.

The College was justly proud of his Band.

But not proud enough to give Buggy money for plumes on the Band’s hats.

So Buggy told them what he really needed was a French Horn to add the final finishing touch.

He said that one French Horn – though notoriously difficult to play – would add “range and richness, and make the high notes sound majestic”.

The Brothers were unimpressed when they saw the price.

They’d spent enough already.

The Buggy fallback position was to squeeze yet another second-hand silver cornet (not a golden trumpet) out of them … and he told me I was in!

The only trouble was that playing a bugle was pretty easy compared with a cornet.

There are no valves on top of a bugle to be pushed down – all the sound comes from how you purse your lips. But with this cornet (just like a trumpet) there were three valves which, when pushed down, changed the pitch to hit different notes.

Three valves might not sound like many – but each note required a totally different combination.

You could push none of the valves down and play it like a bugle, or just the first one, or just the second, or just the third … or all three at once.

Or you could combine one with two, or one with three, or two with three.

Thus to play any particular song you had to know in what order to press the various valve combinations … while all the time creating the pitch with how tightly or loosely you held your lips.

If you could whistle a tune you were right.

Brian Buggy’s genius was that he had quickly realised that very, very few boys could read music and march at the same time. Or even read music.

So he created a special easy way to get a big band together quickly.

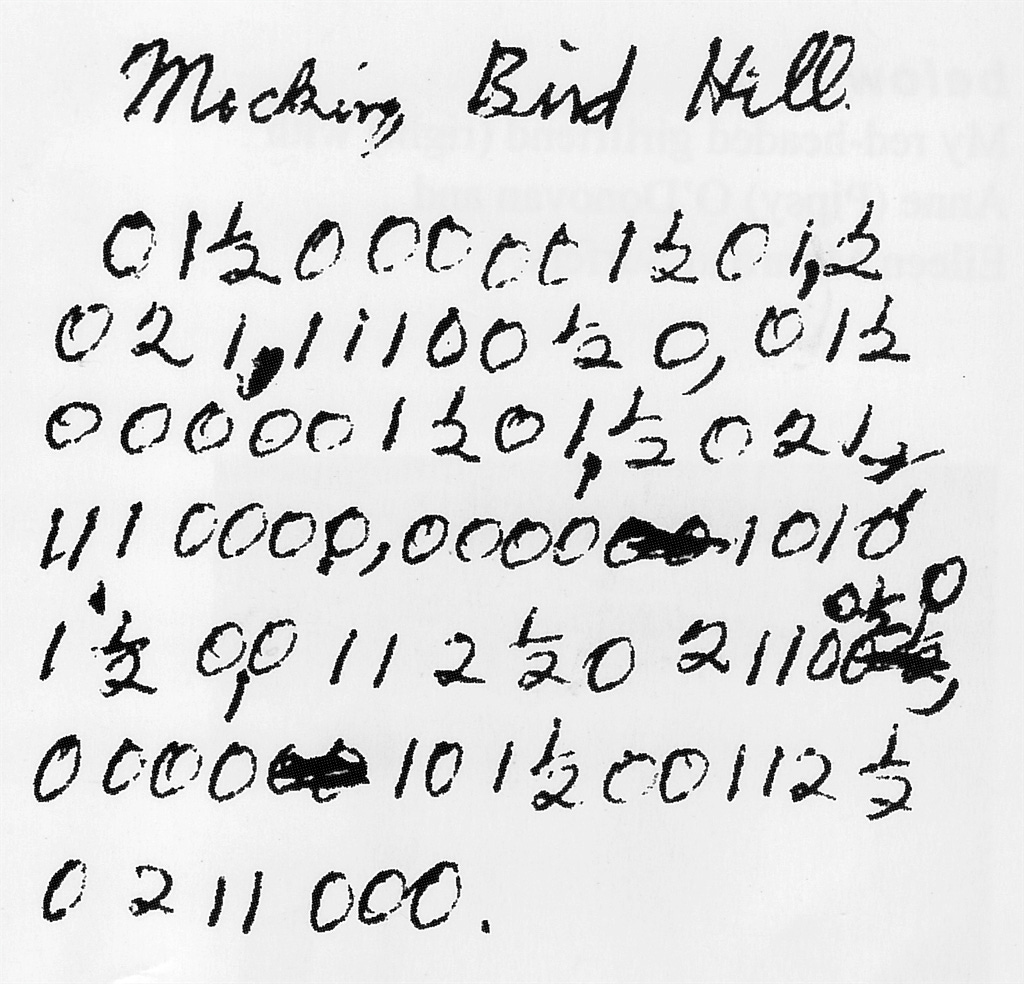

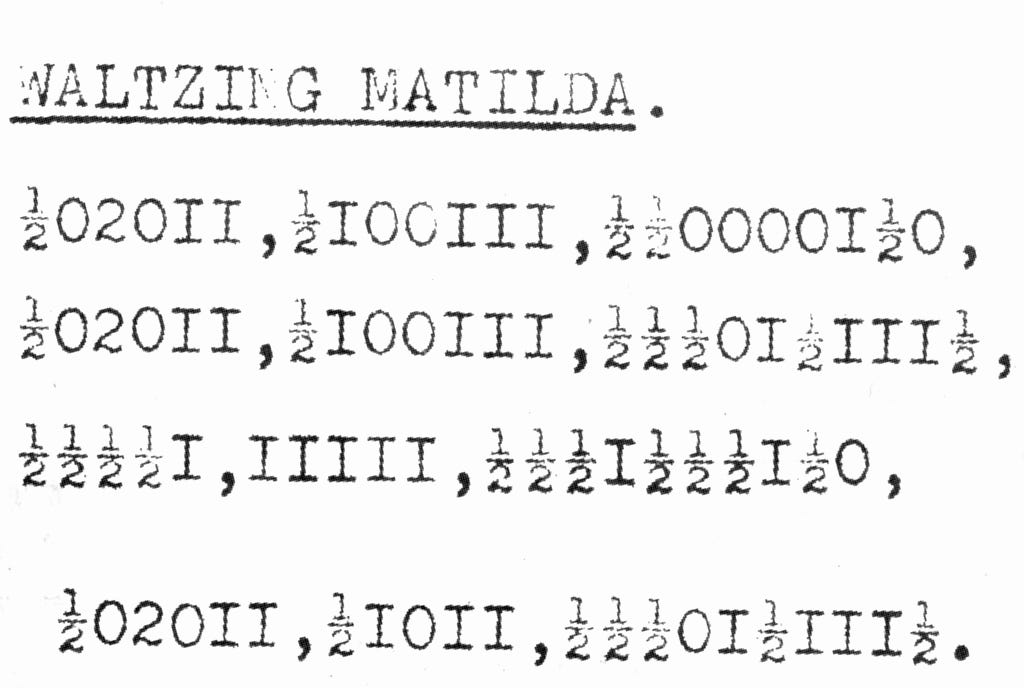

Instead of sheets of music covered in crotchets and quavers. demi-semi quavers, sharps and flats … Buggy typed out the valve fingering for each note in a song.

I guess it was really music by numbers: but it worked.

For example: to play Stars and Stripes you put a typed or hand-written card in the clasp above the trumpet that read:

You knew the tune in your head … so away you went! (You couldn’t get 2/3 on a typewriter so Buggy used ¾ instead.)

He dictated the numbers for Mockingbird Hill and I wrote them down:

To enhance the performance of Waltzing Matilda, he divided the brass into two sections – one played the actual tune while the other played something different, much lower, but which harmonized.

I was put in the harmony section, but found it difficult to play a tune seemingly unrelated while the trumpets behind me were blaring out such a well-known song.

But it sounded great.

On Anzac Day 1956 the entire Terrace Cadet Unit marched through the centre of Brisbane in columns of six – led by our Band! From the Botanic Gardens, and down Elizabeth Street past the Irish Club to St Stephen’s Cathedral.

As I blew Waltzing Matilda like never before, for the first time I experienced the euphoria of being a small part of something beautiful in our city.

I had been lifted out of Purgatory.

We were asked to perform Nearer My God to Thee for a Protestant school Cadet Corp that was camped at Greenbank, so Buggy said it had to be perfect.

The trouble was it contained “High C” and most couldn’t hit such a high note. So he instructed only three of us to blow that note. “Otherwise, we’ll sound like a chook being choked,” he said.

In most schools, the band leader was the Drum Major: which is why he wore four stripes!

The Drum Major strode out front, elaborately swinging a silver-topped mace around his head and using it to signal the Band when to start a new song.

But Sergeant Buggy was no show-off.

He was more interested in the music than starring out front. So he always marched as one of the trumpeters in the back row … even though he’d won the Amateur Hour on radio playing his trumpet.

(That was before TV when evening radio was incredibly popular.)

The Band was also the Field Ambulance and so Buggy taught us to rescue soldiers using the “fireman’s lift” and how to treat the wounded.

“Never give a soldier with a stomach wound a drink, no matter how thirsty he says he is,” is one I still remember.

If a thigh bone (femur) had been broken by a bullet, you applied a torniquet and strapped the soldier’s .303 rifle up the outside of their leg to hold it together.

It was called “a John Thomas splint”.

Sergeant Buggy also showed us the body’s various “pressure points” which, when pressed and held, stopped the artery blood flowing out. (If you didn’t they’d be dead within 20 minutes.)

On Parents’ Day (Sunday) mums and dads were invited to Greenbank to see what their precious boys had been learning.

One group of cadets fought another in a mock battle on an open field, firing blank bullets that only expelled cardboard.

Some cadets were instructed to fall down as though wounded or killed, and Band members rushed through the grass carrying stretchers while keeping our heads low.

Where are you hit?

AAAAH!!! In the leg! AAAAH!!!

We’ll stem the blood.

Then we bandaged him up, threw him on the stretcher, hoisted it onto our shoulders and struggled back through the parents who clapped and cheered.

(Fred didn’t applaud. He didn’t agree with any of it.)

Three years later, Brian Buggy passed Grade 12 and won a scholarship to the Queensland Symphony Orchestra – not just for the trumpet, but also for the violin.

Which was some sort of record.

At the age of 21, Buggy became Musical Director for J.C. Williamson Theatres where for 15 years he directed many of the great Musicals of the 1960s and ’70s: including My Fair Lady, Man of La Mancha and Fiddler on the Roof.

He toured them throughout Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

I felt proud to have known him when, in 1965, I read that Brian Buggy had been chosen to conduct the homecoming Australian tour by Joan Sutherland: at the time the most famous soprano in the world.

She was accompanied by a then unknown tenor, Luciano Pavarotti.

Buggy later took up the position of Head of Music at Knox Grammar School in Sydney where he stayed for 35 years doing what he did best.

When the memoir of my youth, Over the Top with Jim, reached Number 1 on the bestseller list for 1991, I was invited to Sydney to be interviewed on ABC morning radio by Andrew Olle.

So many Brisbane people rang in, that Olle said on air: “Everyone in Sydney must have gone to school in Brisbane!”

One who rang that programme was Sergeant Buggy from Knox Grammar to reminisce on air about our shared days in the Band.

He was now married with two children.

In 1998, Sergeant Buggy was awarded the Order of Australia Medal for his services to Music, particularly in Theatre.

At Knox, he was the driving force behind their student Musicals which uncovered and nurtured the talent of performers including Hugh Jackman, Georgie Parker, Hugo Weaving.

Plus scores of musicians now working in orchestras worldwide.

After leaving Knox in 2007 Brian became conductor for the Sydney Youth Orchestra Philharmonic for 14 years.

In tours across NSW, just as he had done when he was a 15-year-old at Terrace, Brian “wrote and arranged parts so that even beginner musicians could play a symphony in the orchestra”.

During COVID, he took the time to arrange Beethoven’s 5th for every instrument, including ukulele and guitar!

Last month, aged 84, Sergeant Buggy died.

Hugh Jackman revealed the news on Instagram with a picture of Buggy, saying:

"I want to pay tribute to Brian Buggy, OAM.

“He was in charge of music at Knox High School where he taught me, and literally thousands of students across the years, a deep love and joy for music.

"That love has stayed with me all my life.

“Brian’s lessons were filled with humour, and he effortlessly held a room in the palm of his hand. To Brian's family, I send my deepest condolences, immense respect, and unending gratitude."

Me too Hugh

.

As usual: some people send emails instead fo comments for all to enjoy.

I liked this one:

Best yet for memories . Thank you , you never run out of topics.

I have literally hundreds of stories I can tell -- so I'd better hurry up, as I'm 83.

Unlike our media, I like to be unpredictable so no one can guess what I might write about next.

And no politics, of course.

And for those worried about my bein dropped from the under-15 Is (the ninth best) I should add someone else sent a picture of me in the Gregory Terrace First XV where I ended up fullback.

You never know what ill happen in life.

Hugh

This is a truly heartwarming story. Hugh finding where you fit in the camp, and connecting with such a wonderful influence in Brian Buggy. May he rest in peace. Thanks for this wonderful story.