Ian Fleming – before he wrote the James Bond books – worked as a foreign correspondent for the London Newsagency Reuters at 85 Fleet Street.

So too did Freddy Forsyth before he penned The Day of the Jackal, The Odessa File, and The Dogs of War. Freddy left to write a novel in 1965: the year I arrived to work there.

So I can tell you that when it came to adventure, daring, and valor, neither of those famous journalist-authors (or even James Bond himself) came close to Reuters’ pugnacious Scottish war correspondent James Pringle.

When it came to war, Pringle was the real deal.

I worked with Pringle during the height of the Vietnam War for 13 months – sharing a small narrow office in Saigon (and even a Continental Hotel bedroom) with him.

Unlike most Reuter correspondents in the 1960s, young Jimmy Pringle didn’t graduate from Oxford or Cambridge.

Like George Orwell before him, he avoided University.

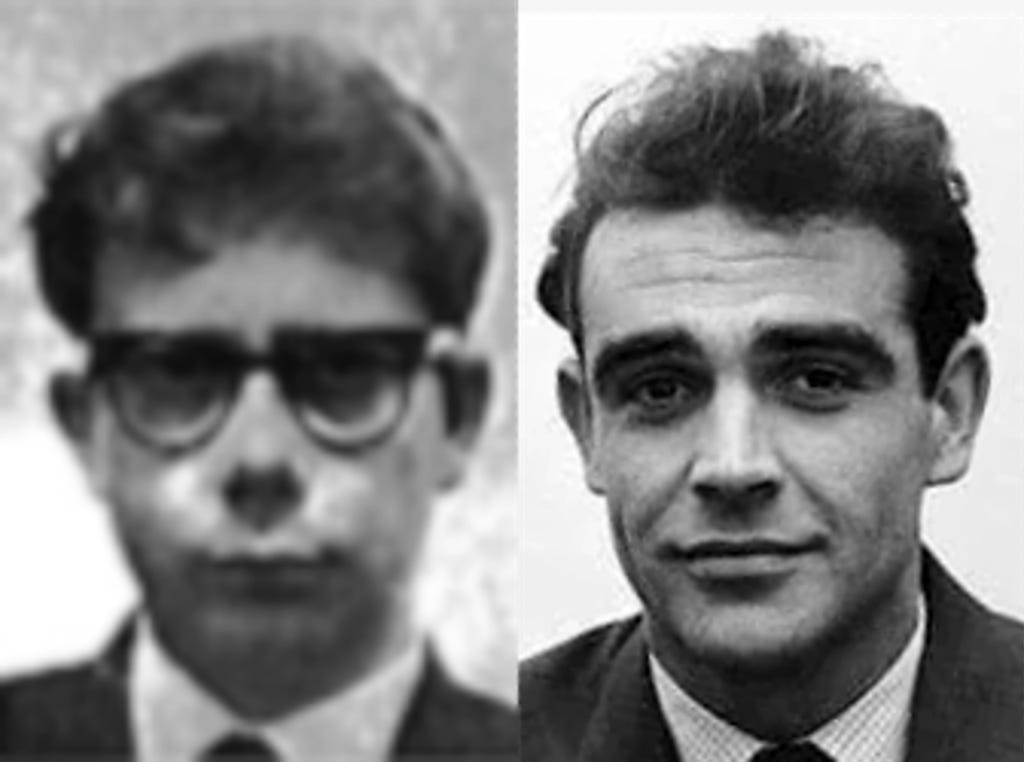

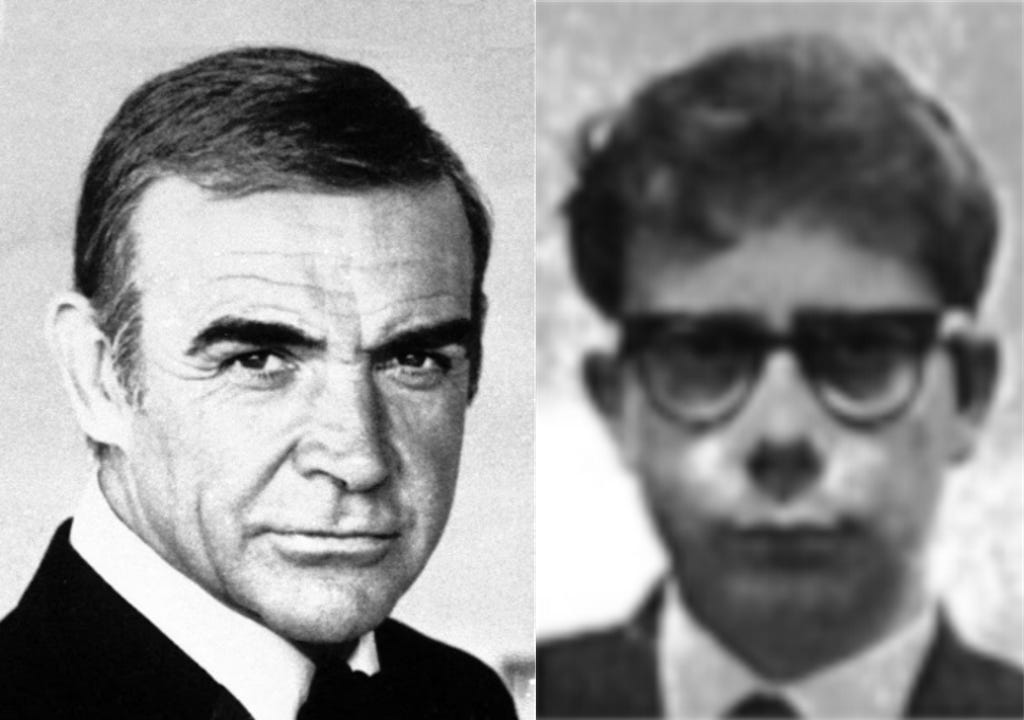

Following in Sean Connery’s footsteps, Jimmy Pringle was born and raised in Edinburgh, left school early, and went looking for adventure around the world.

007 and Pringle always refused to accept the status quo and so both supported the Scottish National Party (SNP) which demanded Scottish independence from the UK.

Jimmy Pringle was only 15 when he joined the SNP.

Also just like Connery, Pringle has always proudly introduced himself as a Scot, an eccentricity which may well have saved his life in Saigon, and later in Peking.

When the Viet Cong launched their Tet Offensive into the middle of Saigon after midnight in January 1968, Pringle was sleeping in the Reuter office.

Bullets started ricocheting off the footpath outside and one made a gaping hole in the brass Reuters sign at the front entrance.

The guerrillas were attacking the Presidential Palace to the left, and the American Embassy to the right … and battles raged throughout the capital for the first time in the war.

No one was safe, but it was important not to be seen as a protagonist.

So, at daybreak, Pringle produced a hand-written cardboard sign and hung it over the bullet-holed Reuters sign outside.

It didn’t say British Newsagency or UK Newsagency or English Newsagency.

Instead, it said in large letters: To Cach Lan – Vietnamese for Scotland.

Then in May1999, during NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, five US-guided bombs hit the People's Republic of China Embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese.

The US said it was accidental; China said it was “a barbarian act”.

In Peking, hundreds of Chinese demonstrators besieged the British Embassy and bombarded it with bricks, paint and stones – because Britain was a member of NATO.

James Pringle, as The Times correspondent, arrived on foot to cover the action, and the furious mob immediately surrounded him and asked aggressively if he was “an English running dog”.

Pringle replied: “No, I’m a Scottish running dog, aye.”

Not realising Scotland was part of Britain, the mob turned away and got on with trying to destroy the British Embassy.

Young Jimmy Pringle first made news when, as an Edinburgh teenager, he walked across the Sahara Desert by himself. Then he went to South America, taught himself Spanish, and freelanced as a journalist in Mexico.

After a stint on Scottish newspapers, Reuters grabbed him.

Normally, you have to work for Reuters for three years before being sent as a foreign correspondent, but, within a year, Pringle was covering the 1965 Civil War in the Dominican Republic, in the Caribbean.

The democratically-elected government had been over-thrown by the military, causing many to rebel.

They wanted democracy restored.

These rebels were labelled “communists” and so in June 1965 US President Johnson sent in the Marines and the 82nd Airborne to support the new military government.

After weeks of battle, a no-man’s-land developed between the two sides. So, during a lull in the fighting, Pringle and a UPI photographer decided to walk across no-man’s-land to the other side to interview the rebels.

They wanted both sides of the story. And they copped it from both sides.

Half-way across, the biggest battle of that insurrection suddenly broke out … leaving the two correspondents trapped in the middle.

Pringle and the photographer flattened themselves as low as they could go, while what seemed like World War III (if you were there) broke out all around.

Literally thousands of bullets whizzed inches above their heads from both sides.

Pringle would laugh ruefully when he told me this story in Saigon two years later, saying that – in the midst of it all – the American UPI photographer suddenly looked across at him and said:

“Well Jim, if we’re going, we’re certainly going in style!”

Casualties were listed as 6,000 rebels and 350 US troops.

Next, Pringle arrived in Haiti which was ruled by the ruthless and violent dictator, “President for Life” François Duvalier – known to all as “Papa Doc”.

Papa Doc was infamous for his “Death Squad” which indiscriminately tortured or killed his opponents.

Because of the danger, Pringle tried to get in and out of Haiti quietly and quickly … do a few quick interviews with the resistance, and slip out with the scoop.

Waiting at the airport for his flight out, Pringle finally relaxed: he had his story.

To pass the time, he tuned in to the rebel radio on his transistor … just in case he picked up some extra information at the last minute.

Suddenly the programme was interrupted for breaking news. Pringle lifted his transistor closer to his ear to hear what immense event was happening in Haiti.

“Good news comrades!” the newsreader announced.

“The fearless Reuters correspondent James Pringle is in Haiti to expose the horrors of the mad Papa Doc!”

Wars and rebellions seemed to break out everywhere Pringle went as a correspondent in turn for Reuters, The Times and then Newsweek.

He ended up in all the worst danger spots: Northern Ireland, Cuba, Vietnam, the Middle East, the Balkans, Cambodia, the Tamil Tiger war in Sri Lanka … and, as he himself put it, “the New York subway after midnight”.

Oh, and in June 1989 Pringle caught a bus to the Tiananmen Square massacre.

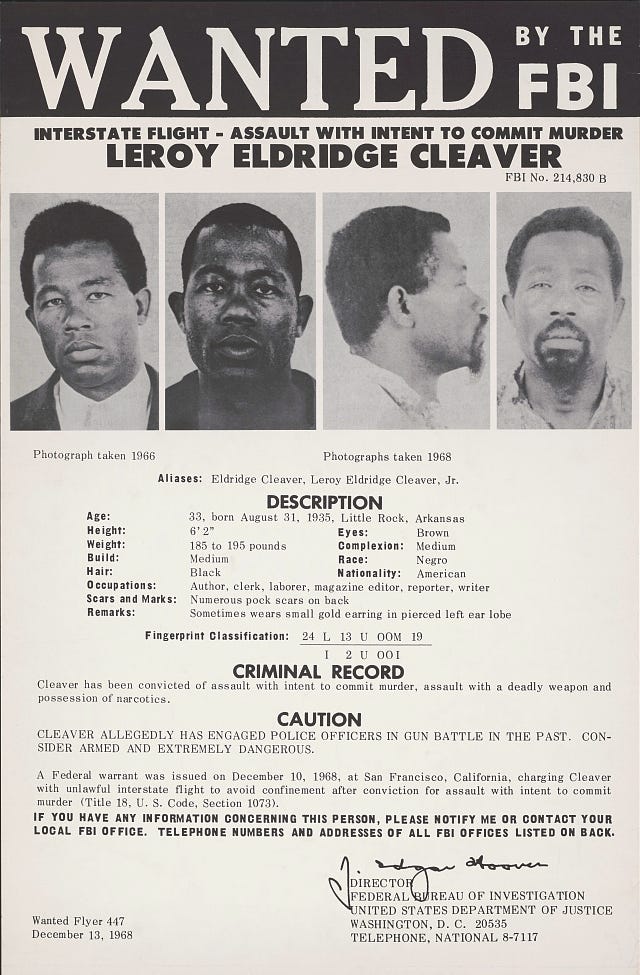

When the FBI couldn’t find fugitive Eldridge Cleaver, the feared American Black Panther leader, Pringle went looking for him.

The FBI had issued a “WANTED NOTICE” which said Cleaver had led an ambush with M-16s and shotguns in which two US police officers were wounded.

The FBI Notice urged “CAUTION” … saying Cleaver was “armed and extremely dangerous”.

But still, Pringle tracked down Cleaver to his hideout in a flat in Havana, Cuba.

He knocked on the door and waited; rather like the Avon Lady or a carpet salesman would.

Three enormous, heavily-armed Black Panther guards opened the door.

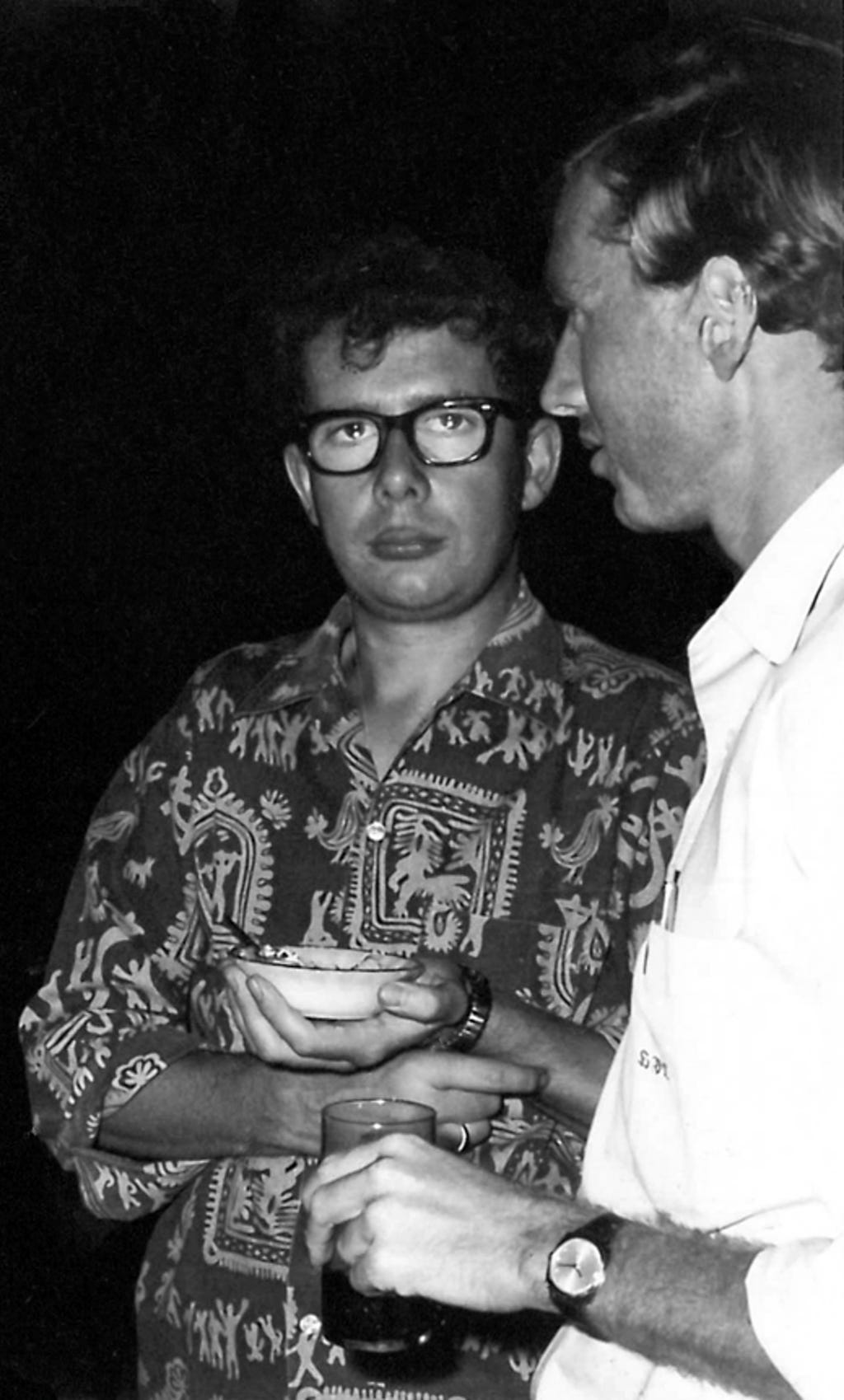

They looked down and saw a wavy-haired pale-skinned man of about 30 with rosy cheeks. He was shortish, thin-shouldered, armed only with a notebook and biro, and looked up at them through Coke-bottle glasses which made his blue eyes disconcertingly large.

Pringle introduced himself in his thick Scottish burr finishing with “aye”.

He worked for Reuters; he wanted an interview; and he wasn’t leaving until Cleaver spoke to him, aye.

Pringle’s interview made the front page of every major American newspaper, some headlines highlighting his revelation that Eldridge Cleaver, fugitive from justice, was in communist Cuba writing a book.

Thus Pringle was a legend in Reuters London office.

When Reuters announced in 1966 they were sending him to cover the Vietnam War, I asked the obvious question: Why Pringle again?

“Well, we’re certainly not bringing him back to London,” said the editor, “we don’t want war breaking out on Fleet Street!”

When I arrived in Vietnam a year later in February 1967 the one person I was looking forward to meeting was this James Pringle. I envisioned someone slightly bigger and more handsome than that other Scot, 007 Sean Connery.

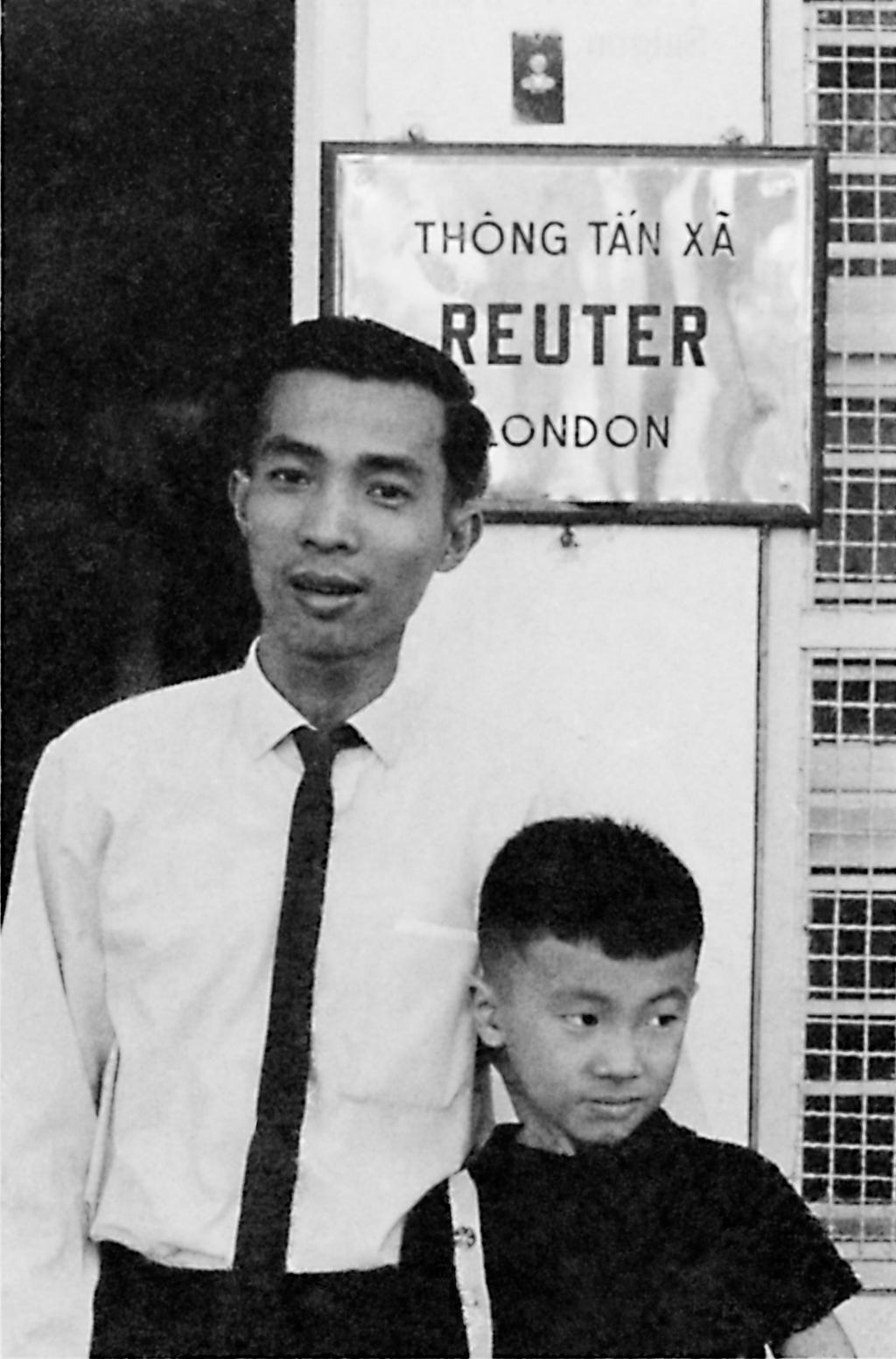

Walking into the very narrow Reuters office at 15 Han Thuyen Street, Saigon, I tried not to look surprised … surely this couldn’t be him?

I searched the soft peaches-and-cream smile for some clue that this was the intrepid James Pringle.

I noted, I thought, an almost deadly fix of those blue eyes magnified by the thick glass in his spectacles.

When he stuck out his hand I expected him to say “James … James Pringle”. Instead he said, with an exaggerated Scottish lilt: “Is that you Hugh?”

Over the next 13 months Pringle and I ended up in some dangerous situations … separately and together.

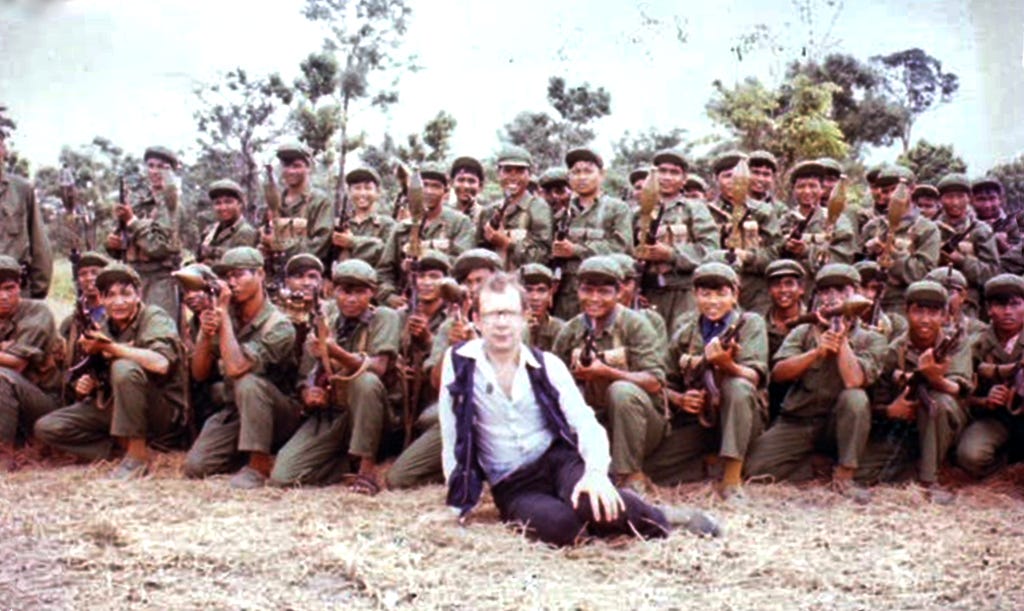

While most war correspondents who went out in the field wore American military uniform (so they wouldn’t be accidentally shot by American soldiers), Pringle had his own uniform: blue office trousers with a narrow black belt … and a Vietnamese camouflage jacket, a bit too tight, that he’d picked up inexpensively at a market.

When the US Marines were heading north to the Demilitarized Zone bordering North Vietnam in a column of tanks, Pringle wanted to see what was going on.

He’d heard they were evicting Vietnamese villagers from their homes and turning them into refugees.

You couldn’t go into this area in 1967 in less than Battalion strength.

So Pringle had no way of getting up there.

He stood on the side of the dirt road and held out a thumb. Eventually, a US tank stopped and Pringle explained he was a journalist trying to get to the DMZ.

Would they give him a lift?

“We can’t take a journalist,” the Yank tank commander said, “but tell us you’re a tourist and we’ll take you.”

So undercover Pringle got his story and told the world what was happening to Vietnamese villagers.

In Saigon every afternoon at five the Americans held a press conference giving their version of the war.

Because of the often bitter banter between the high-ranking military spokesmen up on stage trying to sell “victories” to a theatrette full of by now mostly cynical journalists, this became known as “the Five O’Clock Follies”.

Pringle’s pugnacity meant that he took on the briefers with questions such as:

“Why is it that you can tell us how many Viet Cong you killed this morning … but the news that you accidentally shot up a Vietnamese village was delayed two full days so that none of us could go and see for ourselves what happened, aye.”

One frustrated colonel, under intense questioning from Pringle from the front stalls, finally blurted out: “How are your friends in Peking, Pringle?”

Back in the office Pringle typed a letter to General William Westmoreland, commander of US forces in Vietnam, saying:

“Reuters has no friends in Peking. Our correspondent in Peking, Anthony Grey, is still under house arrest in his basement being ill-treated by the Red Guards who slaughtered his cat before his very eyes … and Reuters cannot get him out.”

(Grey was held in Peking for 27 months.)

A few days later that same American colonel, in full military dress and bristling with medals, marched through the front door into our office between the facing desks where our Vietnamese reporter Pham Ngoc Dinh and I sat opposite each other … until he reached Pringle sitting at the back.

There he saluted Pringle and spoke: “Mr Pringle I apologise most sincerely for my comment about Peking.”

The colonel saluted again, about faced, and marched back out before anyone could say anything.

Dinh’s already great admiration for Pringle tripled.

The Tet Offensive of January-February 1968 was the defining event of the Vietnam War. Before, everything was buildup and optimism. After, everything was recrimination and withdrawal.

Within a month President Johnson announced he would not stand for office again; and General Westmoreland was withdrawn after four years of hopefulness.

Tet was listed as the biggest story in the world for 1968 because the Viet Cong – said for years to be on their last legs – secretly entered Saigon in force and captured (briefly) “Pentagon East’: the white fortress American Embassy in the middle of Saigon.

Fighting in the city continued for weeks.

The US had some 10,000 intelligence men including CIA agents in Vietnam, yet they didn’t know the VC were in town until things started blowing up.

But strangely, Pringle and I knew they were coming. Our friend and fellow Reuters reporter Dinh had warned us.

Dinh had been tipped off by TIME Magazine staff reporter Pham Xuan An from next door. Only later did Dinh learn for sure that this Pham Xuan An was working for both sides.

While writing for TIME, An was also a Viet Cong Colonel.

After the Fall of Saigon seven years later, in 1975, Colonel An was promoted to Major-General and lauded with the title “Viet Cong hero in the South” for his inside revelations during the war.

It’s a long, long, detailed story told in my Vietnam book … but suffice to say that, when I finally reached the office at dawn the first day of Tet, Pringle looked up from furiously typing and said:

“It’s been terrible Hugh!” … and I realised just what was upon us.

I never expected to see Pringle exhausted and, if it were possible, scared.

The night before, with rockets landing and Viet Cong at the front door, Pringle hid under the stairs writing stories by hand to send to London.

So that morning James Pringle himself was shaken and stirred.

“Get down to the American Embassy Hugh, the Viet Cong have got it,” Pringle said.

As I reached the door, he added: “Watch out for the sniper across the road!”

That night, our incoming telex failed and the only way to check what had gone wrong was to somehow get to PTT (Post, Telegraph, and Telephone) HQ in Cholon (the Chinese quarter of Saigon) three miles away … where the street-to-street fighting was the worst.

The office VW came under fire and Pringle and Dinh were forced to jump out while the car was still moving and it rolled into a tree.

I knew nothing of this (no mobile phones in 1968) but, after several hours, I thought Dinh and Pringle were never coming back. I became convinced I was now covering the Tet Offensive all on my own.

Eventually the pair staggered in, covered in dirt … and without our VW.

Dinh was in tears: “Gunsmoke [his nickname for me] I cry and cry. The bullets go over my head.”

Acting out the scene, Dinh said: “I crawl behind a tank but Jim says ‘No they have rockets’. He crawls in one direction then another one, but each way there are bullets.

“One policeman waves us but a bullet goes through his hand. I try tell Jim something, but nothing comes out. I want tell him: ‘look after my wife and sons, and when they grow up not be journalists’.”

Dinh said that eventually Pringle saw a child wandering alone in the middle of the road and, under fire, ran and picked her up and carried her to safety.

Dinh followed and they made it to a house and knocked desperately on the front door.

But a Chinese woman in Vietnamese yelled “Go away! This is a communist house!”

She thought they were the Viet Cong and so wouldn’t let them in.

For the next two weeks Dinh and I slept on the floor above the office in Pringle’s single room.

After four days of guerrilla warfare throughout Saigon I was typing away when I looked out the door and saw Vietnamese Red Beret government troops stretched along the footpath outside.

Their task was to search central Saigon block-by-block and root out any VC.

One of them rested his M-79 grenade launcher on the roof of our recovered VW… aiming it through the upstairs window of the Reuter office.

They had just dragged out a Vietnamese telex operator from TIME Magazine next door because a rifle had been found near him. Today I wonder whether that rifle belonged to Pham Xuan An or even to the TIME cook who, Dinh later learned, had been hiding a VC leader in her servant’s shack out the back.

But the American military knew nothing of this.

The Red Berets sent three white-uniformed South Vietnamese policemen (known as White Mice) into our office to conduct a search while they stood outside ready for action.

As Dinh and I watched, the three policemen walked single file between our facing desks, their large silver pistols cocked and pointed at the floor 10 feet in front of them.

Pringle popped up from his Bureau Chief’s desk at the back and stepped forward. Holding his right hand up like a stop sign – his face a mask of determination – Pringle said: “And where do you think you’re going?”

Dinh started laughing and I told Pringle to wake up to himself and get out of their way!

But he turned and looked at me in surprise: “But Hugh, it might be censorship or something, aye.”

The pistols-drawn police explained they were searching for weapons and identity cards – so Pringle graciously allowed them to pass.

James Pringle during his career looked at war through the eyes of those who suffered most.

When the US military flew reporters to a battlefield in the Mekong Delta to show off a rare victory over the Viet Cong, every reporter wrote how many VC the US had killed: from memory, it was189.

Pringle wrote instead:

Viet Cong child soldiers lay like broken dolls along the banks of this canal today, and an American sergeant said: “If they’re old enough to pull a trigger they’re old enough to die”.

Like the hero in a Charles Dickens novel, James Pringle displayed quirks of character that could surprise his friends.

Despite fighting for Scotland’s independence all of their lives, Sean Connery came home to Edinburgh to accept a knighthood from the Queen in 2000 … and, in 2022, aged 85, Pringle went to St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, where he joined the queue to file past the coffin of Queen Elizabeth II.

Perhaps it was because the monarch’s coffin was draped in the Royal Standard of Scotland or perhaps because the Crown of Scotland was placed atop for the last time.

Or maybe, it was because Pringle had always advised me as a reporter: “You are allowed to observe what happened, aye”.

Postscript: James Pringle and his Cambodian wife Milly are retired and live in France.

Pringle and Dinh, the unforgettable hero and anti-hero. Makes me want to reread your memoir Vietnam: A Reporter’s War, along with that other classic, Dispatches by Michael Herr.

Absolutely loved this story Hugh, always fascinated how you weave history, humour and fact into such entertaining reads, thank you 😁