Journalists all around the world dream of one day writing a story that no one else has: a scoop.

But international scoops are as rare as typewriters.

In 1967, during the Vietnam War, the US Navy – perhaps because they’d been starved of attention for far too long – decided to launch a surprise naval raid on North Vietnam at the height of the war.

To ensure nobody back home missed their action, the Navy invited along Time Magazine, Newsweek, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Baltimore Sun and world wire services (news agencies) A.P., U.P.I., and Reuters.

As one of four Reuters war correspondents in Vietnam, I was assigned the job.

“Board one of three destroyers headed for the Gulf of Tonkin in the South China Sea and watch them bombard Communist North Vietnam.”

As we steamed north through waves a couple of metres high, I got to chat to the captain on the Bridge of the USS Ault. He sat in his captain’s high chair in the right-hand corner scanning the horizon through binoculars.

Conscious of my own hide, I wanted to know how thick the steel hull of an American destroyer was.

“Below the waterline, y’know, we are five-eighths of an inch thick,” the captain answered, “but above the waterline we’re three-eighths of an inch at the thickest part.”

He must have seen my face drop: I assumed a war boat would be protected by metal several inches thick.

“Weight stops a train, y’know,” he said. “The skin is kept thin to make a destroyer fast and able to manoeuvre out of the line of fire quickly. Which will come in handy when our convoy makes our runs along their coast. We’re shelling roads and bridges, y’know.”

How fast? I asked.

“The top speed of an American destroyer is a secret,” he answered abruptly, squinting at me as if I were a spy “but it’s over 35 miles per hour.” He lifted his binoculars and turned away, still scanning the horizon.

Had what we were doing been tried before?

“Yeah,” the captain replied. “We sent two destroyers up here three years ago in1964 … just before the war took off.

“When one of our destroyers, the USS Maddox, arrived in the Gulf of Tonkin three North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked – launching 20 torpedoes.

“Enemy aircraft were also sighted overhead, y’know.

“The Turner Joy, another destroyer, arrived in support; two days later it came under attack as well.

“Only a week later, Congress – in Washington, y’know – voted … it was almost unanimous … and the President – Johnson – was able, was authorized … and now we’ve got hundreds of thousands of troops here sorting out those Communists.”

(Now, the United States had more than half-a-million soldiers in Vietnam, or “in country” as the Americans said it.)

Are we expecting any torpedo boats? I asked.

“In war you must expect everything, y’know. War is utter boredom interspersed by moments of sheer terror. (This wasn’t a cliché in 1967.) But this time we have three destroyers, not two.”

Thank God then for the four eight-inch diameter guns – mounted on the front just below my line of sight – pointing menacingly towards the cloudless hot blue tropical sky: and, for good measure, two more eight-inch guns at the back.

“How far can those guns fire?” I asked the captain, searching for a story as we breezed choppily along for hours. (Destroyers, I found, were such narrow top-heavy ships that they tended to roll from side-to-side: unlike an aircraft carrier which rolls from back to front.)

“Eight miles.”

“Wow!” I said. “That’s a long way! So we’ll be staying safely away from the North Vietnamese while shelling them?”

“Yes, it is a long way,” the captain replied, as he again frustratedly lowered his ever-present binoculars, “but, y’know, their land-based guns fire 12 miles.”

What?

It didn’t take much mental arithmetic for me to work out that for four miles on our way in to attack – and for four miles on the way back – the Communists would be able to shell us … and we couldn’t fire back!

“Affirmative,” said the captain matter-of-factly, “it’s known as the five-minute critical zone.”

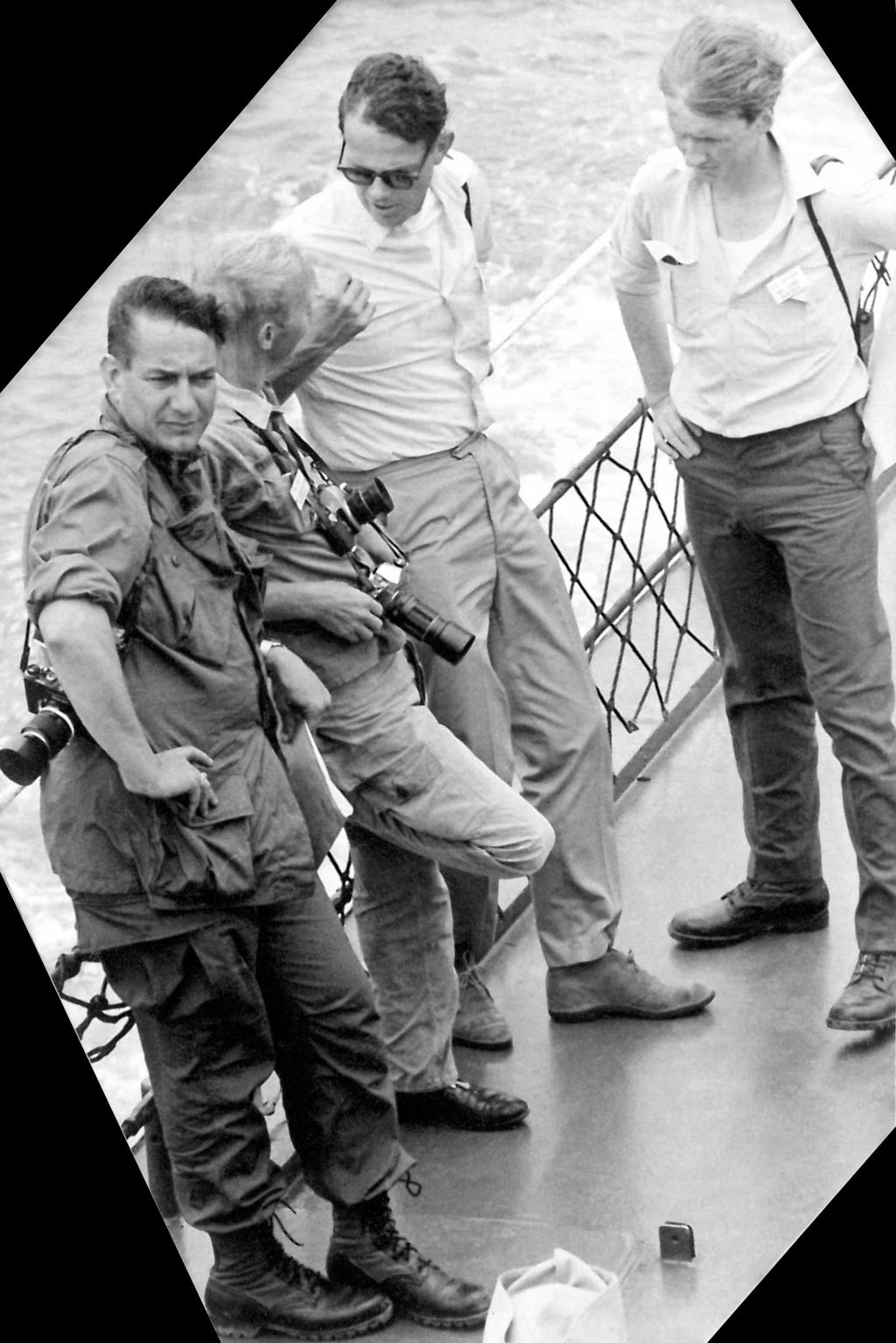

We were interrupted by two naval officers.

In readiness for the raid, I was to be moved with two other reporters from the USS Ault to one of the other destroyers: the USS Shelton.

No one said why, or how this decision was made, but the journalists were being dispersed to all three destroyers. (I suddenly realised that the US Navy thought it would be bad publicity if they lost all us reporters to one shell.)

But how were they going to move us?

They couldn’t pull into a harbour on the shores of North Vietnam. So I assumed they’d launch a life boat: but I hadn’t seen any on board. Or they’d pick us up by helicopter – but there were none of those way out here. Too far.

Perhaps, I decided, we’ll stop in the ocean and “come alongside” like in the old pirate movies.

But the rough seas would make that impossible to do safely.

As we steamed along out of sight of land at 30 knots, I noticed that the three destroyers were slowly moving ever closer together … as if lining up for a race.

When the Shelton and our Ault got within 50 yards of each other, I found out just how it was going to happen.

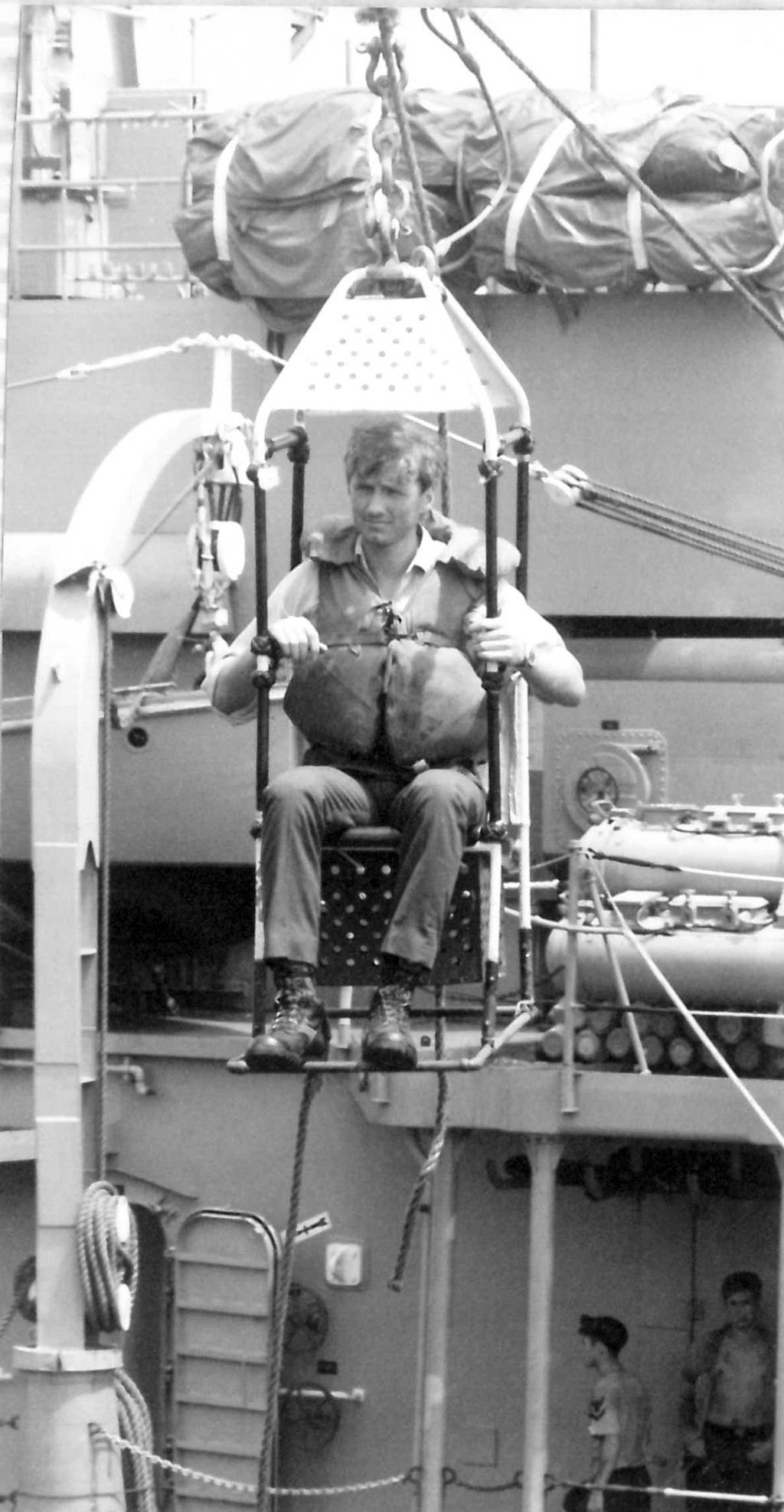

Two sailors strapped me into a large pumped-up life-jacket while a guide-rope was launched from our ship to the Shelton. The sailors then used this rope to haul a thick cable across the gap between the ships, and they brought out a high narrow chair.

It was called a “personnel basket” so I thought they would be moving some sailors to the other ship … until I was told to strap myself in and hold on tight.

The chair and me were then hoist up. That’s when I noticed the other reporters taking photographs of me. It made me faintly uneasy: as though I was going to be the story.

Sitting in the “basket” high above the deck – with journalists and sailors watching my feet dangling over the edge – I looked down. It was like being on the edge of a cliff above a bottomless pit … the only thing below was a churning ocean of unknowable depth.

As they set me off towards the Shelton, across the South China Sea, it felt like flying through the air until … I dropped suddenly and unexpectedly towards the swift, heaving, blue channel created between these two racing destroyers.

To bring me back up higher – away from that lurking, swaying, roiling, sucking deep – sailors on ropes pulled on my cable as though they were in a tug-of-war with nature, and I was simply the little white handkerchief loosely tied in the middle.

Uh-oh!

I was now moving higher than the decks of both ships! The cable above strained and tightened. Then I dropped again.

One of the ships must have rolled outwards.

I could now see that if these two destroyers didn’t stay exactly parallel I would be beneath the ocean while moving forward at 35 miles per hour. Or, the other alternative, crushed between two lurching steel hulls.

But – if these war ships moved too far apart – my lifeline, and my life, would be snapped by their irresistible power.

What was I doing out here above the ocean, by myself, anyway? Why hadn’t I stayed on my destroyer like most of the other journos?

Everyone back at Reuters in London, or at home in Brisbane, was going shopping, or out to see the latest movie – yet here I was in a place where nobody else could ever expect to end up: whipping through the air above an ocean on the end of a rope.

Nothing could save me if things went badly wrong. I was in the hands of others, and I didn’t like it.

Why had I always found my way into trouble ever since Primary School? Fighting State School Kids; a Russian classmate rubbing my ears just because I’d called him “a Communist pig” and stabbed him with a lead pencil; copping the lawyer canes of the nuns.

Punished by leather straps at secondary College; kicked out of Communist China two years before this moment; then held overnight in Russia by soldiers at a border railway station.

Only recently in London two thugs had threatened to break my arms at 4 a.m. in a Chelsea arcade. Now that doesn’t happen to many people.

And more recently ambushed, shot at, and mortar-bombed with the Marines when they went into the Hiep Duc Valley.

It's amazing what comes back to you when your end might be nigh.

Was it some fault in my character that made it too easy to find my way into trouble?

Or was I easily led?

When my boss at Reuters at 85 Fleet Street, London, had told me they were sending me out to Vietnam, he said: “We want you to sit on a hill and watch the battle and then report back to us.” But the job ended up nothing like that.

Nothing so simple.

Nothing like this.

The boss did arrange lunch for me in the Reuters canteen with a returned Vietnam war correspondent, Jonathan Fenby, who would fill me in on the details.

When I sat down ready to take notes on “reporting for war” with the cheerful young Englishman, he surprised me: “Hugh, do you like marmalade?”

Yes. Who doesn’t?

“Well,” Fenby said conspiratorially, “before you fly off to Saigon, get down to Harrods and buy a box of Cooper’s Oxford Marmalade – it’s the best there is! You just can’t get marmalade in Vietnam!”

None of these thoughts seemed able to sufficiently explain what I was doing strapped to a chair suspended above the ocean between two ships which were charging off to a battle.

I breathed again when I came back to earth on the deck of the USS Shelton: ready for war.

North Vietnam appeared as a thin line of blue hills half-hidden in a soft white mist.

Our three sleek grey destroyers closed on that coast, six guns apiece pointing towards the shore.

I was now on the Shelton’s Bridge looking through the glass front with my new captain and six of his crew: the only men allowed outside during the assault. The gunners were inside their swinging steel turrets and the rest of the crew sweated it out down below the water-line where at least the steel was thicker.

As we plunged doggedly west towards North Vietnam, the helmet and flak jacket I had been issued made me so top-heavy it was difficult to stand still and not sway around.

Only now – while searching the horizon for torpedo boats 15 miles from the fast-approaching North Vietnam coast – did I realise that sailors didn’t have it as easy as soldiers thought.

Nor could I help thinking that it seemed strange that these men who had never seen a Vietnamese were now intent on killing some.

We were almost in the five-minute critical zone.

“Captain, they’ve got a fix on us,” called a crewman on the Bridge.

Apparently a shore-based radar had picked up our presence when we were 13 miles out. There was an island to our left: “Captain, they’re trying to get a fix from the island.”

The captain said the North Vietnamese gunners had to get two separate fixes on our destroyers so they could bring accurate fire down upon us.

As we rocked and rolled to within their artillery range of 12 miles, the Bridge team did something I didn’t understand, in order to throw the Communist radar stations off.

The captain picked up his microphone:

“Now hear this! Now hear this! … We are now going in under the muzzles of enemy gunfire to attack an enemy bridge and highway. Good luck!” and he placed the microphone back in its tiny cradle.

We were following the Ault and the Collett as our sharp front plunged down and up through the waves throwing water high up over the Bridge glass.

The palms of my hands started to sweat involuntarily as I recalled that one direct hit in the right place would disable a destroyer … and I’d been told that that right place was the Bridge.

The Ault turned a sharp right … then the Collett … and then our Shelton: each with their guns all turned hard left towards the land.

Mustard-coloured smoke rings appeared above the guns of the Collett ahead as the attack began.

Suddenly it occurred to me that our destroyer would be last out of here.

I was now rocking visibly.

The four guns in front of me moved mesmerically as our ship’s computer kept adjusting the barrels to stay on target despite the lurching of the ship from the pitching ocean.

We were through the critical zone because the captain again reached for his microphone and said to the gunners “Fire when ready!”

There was a deafening blast and flames and our ship shook as if punched on the jaw.

“We’ve been hit!” I thought: but the tongues of flame were belching from the lips of our guns … followed by our very own clouds of mustard smoke.

Every seven seconds our guns fired again. I kept thinking of that poem we learned at school “Don John of Austria has loosed the cannonade!”

I wanted to make notes in my notepad but I was too unsteady.

“Enemy fire!” warned the Battle Planner on the Bridge, but I later found out that the report of a shell bursting nearby was wrong.

The captain handed me his binoculars so I could see where our shells were bursting.

Water on the shore was spraying high into the air. “Too short! too short!” called the captain to the gunners.

Each time our six guns fired, the ship seemed to roll to the side and I jumped because of the noise – even though I knew what was coming as I counted off the seconds.

It was now every eight seconds as the gunners loading the heavy shells tired.

White smoke burst in through my binoculars as white phosphorous shells (known as “willie peter”) burst among the trees beyond the beach. These were used so we could see where the shells were landing.

“Dead on!” called the captain.

Twice more we made runs along the North Vietnamese coast, firing all the way … and each time I felt more and more seasick.

As we withdrew successfully through the five-minute critical zone the captain announced over his loud speaker that a US plane circling above our target area reported back: “Direct hits! Targets destroyed!”

Some of the other journalists were unhappy that we had not been fired at, which would have given them a bigger story. However, the Navy revealed later that artillery shells had been fired from shore but had landed harmlessly in the seething ocean.

As soon as the raids were all over I removed my helmet and flak jacket and rushed down to the nearest toilet.

A Lieutenant Duncan – who had offered to lend me his typewriter – then helped me along to the ship’s medic.

The doctor examined me, produced an injection, and turned to Lieutenant Duncan and said: “Would you please leave the room for a moment, Lieutenant.”

Turning to me he said: “Drop your trousers and bend over” – and jabbed in his needle. “You’ll have a good sleep now, and wake up refreshed.”

I was distraught. I had yet to write my story and send it to Saigon.

When Lieutenant Duncan returned, I told him my problem. I was already starting to feel woozy.

So Lieutenant Duncan typed as I fought off sleep to dictate my story to him – in between vomiting into a bucket. As I drifted off, the trusty Lieutenant took my story to the radio operator to send straight to Saigon.

What I didn’t know was all of the other journalists on the three ships were welcomed to victory drinks in the Officers Dining Rooms before writing their stories.

As soon as Lieutenant Duncan had sent my story, a warning was issued that torpedo boats had been spotted heading our way, and all three ships went on complete radio silence.

So my Reuters story was the only one that was out there when San Diego’s biggest paper picked it up and splashed it right across the top of the front page.

My story suited the paper perfectly because San Diego was the world’s largest surface-ship naval base.

I had scored a seasick scoop.

And the time I scooped myself? You can read how I did that in A Four Day Truce.

That's a brilliant observation Peter: "once a scoop always a scoop".

You are definitely becoming a writer --- since you moved to the bush. Perhaps there is extra time for thought. That's what you need to think of original ways of putting things.

The word 'SUPERB' sums it up. An extraordinary story brilliantly told. Helga