I once knew a man who was the master of the one-liner. Not in London, or in Singapore, or even in Sydney – as you might expect.

It was Brisbane in the 1970s where that rare skill took him to the top of the Queensland banana tree.

But life likes to even things up.

In 1987, aged 47, he phoned me at home at 6 o’clock one morning to tell me the police had arrived to take him away to prison.

All he said was:

“The crucifixion will be a little early this year.”

We’d first met in 1971 when I returned home to Brisbane after seven years overseas.

Even though I’d worked for the London Daily Mirror, the London Sketch, and as a re-write man in London for Reuters and then as their correspondent in Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia … none of the Brisbane newspapers would give me a job.

Not even the paper where I’d done my cadetship, The Courier-Mail.

“Unfortunately for you, a couple of bright young men from Sydney have applied,” they said.

Though I had no experience in radio or TV, I applied for work at the ABC (the public broadcaster then known as the Australian Broadcasting Commission) where, luckily for me, their political roundsman had just resigned.

He had been offered the job as press secretary to the Queensland Premier: but first he had to serve out three months’ notice.

The ABC, of course, couldn’t have the Premier’s future PR man covering state politics … so he was put on the sub-editor’s table checking other reporters’ stories before broadcast on radio and TV.

I was hired as his replacement.

When I arrived at the ABC, I met him: a largish, self-educated man with deep-set blue eyes, thick black hair, long dark sideburns, and the heavy gait of a train driver who had to always keep one foot firmly on the floor.

The ABC’s Brisbane headquarters spread across a huge piece of land on the wide river.

Mystifyingly, they had chosen to build their offices almost on top of one of the city’s busiest roads (Coronation Drive) … with huge garages built out the back on the bank of the river.

These garages had magnificent city views looking east down the river.

Another weird thing.

The ABC newsroom was downstairs in the basement … and sure enough it finished a few metres under the Brisbane River three years later in 1974 when a HUGE story – in guise of a massive flood — arrived.

At 30, I was ten years older than most of the reporters in that newsroom … including young Andrew Olle who later became famous after he moved to Sydney. (The Andrew Olle Memorial Lecture is now the premier annual media event in Australia.)

The multiple news bosses were decades older than me and had their own large separate offices.

But here, unlike at a newspaper, there was no Library: all they kept for reference were yesterday’s stories. On the other hand, incongruously, there were dedicated typists for the newsroom. Plus no end of large, white, sparkling tea cups and saucers neatly laid out.

As there was no canteen – and the nearby shopping strip offered only a greasy fish-and-chip shop – when not working we sat or stood around the office drinking tea and chatting.

I found myself gravitating towards the jovial sub-editor whom I was replacing: I didn’t even know the name of the Premier, so, as the ABC’s brand new political roundsman, I needed to quickly absorb information.

Though he’d left school at 15, this bloke knew his onions.

He had been an ABC producer and director of radio and TV news bulletins and had worked as a journalist in the national capital, Canberra, for five years before returning home to Brisbane.

So I also sought his advice about writing for radio and TV.

His name was Allen Callaghan, and I liked the fact that, although he was two years older, he always referred to me as “Monsieur”.

I don’t know why he did this, but he did.

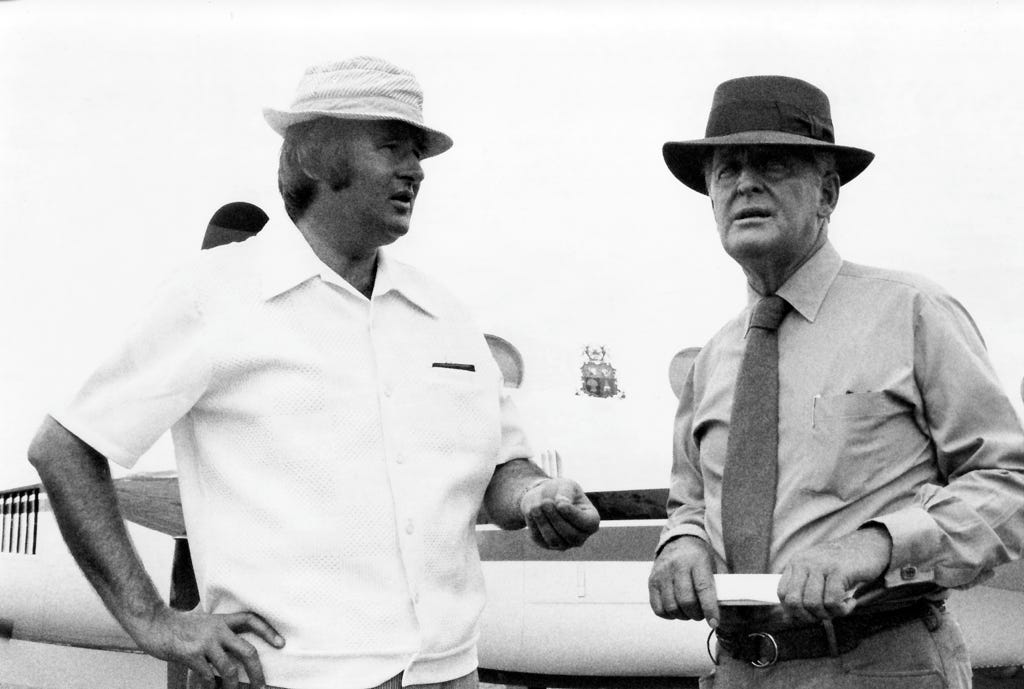

In my second week I was sent out to Brisbane Aerodrome with an ABC TV crew to interview the Prime Minister of Fiji who had just arrived.

This was done on the basis that I’d “worked overseas” – even though I’d never been anywhere near Fiji.

At the press conference in the VIP Room, none of the 20-year-olds from the three commercial TV stations wanted to go first, so I waved the large microphone in front of the Fijian PM for my first ever TV interview.

I only knew one thing about Fiji.

“Now, Mr Prime Minister, how is the problem going with the Indians in Fiji?”

He stared intently at me and replied: “What problem is that?”

I was stuck with the camera rolling, and stumbled and mumbled incoherently for the four minutes it took in those days for the film to run out.

Should have kept my day job.

TV reporting could not have been more different from newspapers where you could spend hours alone writing a report. Here, my indecision, my every frown, hesitation, and stammer was being captured for all time.

Back at the ABC, all the staff were invited to the theatrette to watch that piece of film; as a learning experience I guess, but it seemed to be more just for the laugh.

Afterwards, needing some reassurance, I asked Allen Callaghan what he thought my future now held and, squinting from under thick eyebrows, he replied in a heavy Nazi accent:

“Your finghernails vil grow Ha-gain.”

It was a pity when Callaghan’s knowledge and sense of humour left to take up the appointment with the man I now knew as Premier Johannes Bjelke-Petersen.

Before leaving, Allen Callaghan filled me in on the recent political landscape.

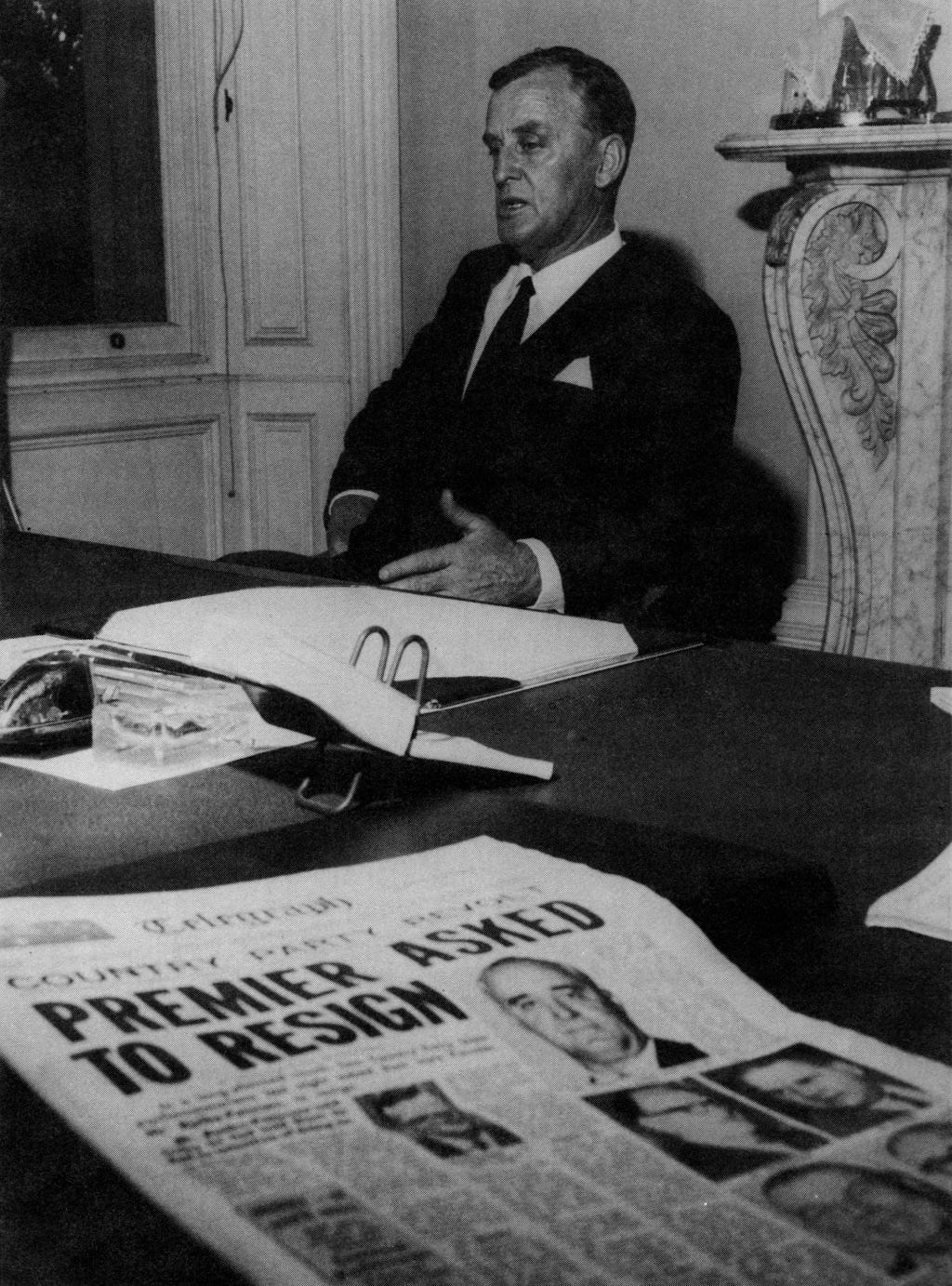

The inarticulate Premier’s own Country Party had tried to oust him because – as a non-drinking, non-gambling Lutheran lay preacher born in New Zealand – he was seen in the electorate as a peanut-growing puritanical wowser (a fanatical teetotaller).

Because he flew his own light plane out bush, some journalists christened him “the Flying Peanut”.

Premier Bjelke-Petersen had only survived that coup attempt by one vote – when he broke political convention and voted for himself.

Desperate to overcome their leader’s prudish image, the Country Party hired a national PR company … who sent him out to Doomben Racecourse to pose for photographs patting a racehorse named Kionda.

This from a man who earlier in his parliamentary career had not only spoken out against gambling, but had opposed the broadcasting of horse races on radio.

Callaghan had cut this photo out of the paper, pinned it up on the ABC staff noticeboard, and written underneath:

A new entry into the Political Stakes. Expediency, by Necessity, out of Politics. His previous entry, Principles, scratched at the barrier.

Asked about this, Allen Callaghan said Bjelke-Petersen should be his own man, or give politics away.

Callaghan told me that his ABC-TV interviews with the Premier would become so labored that he had to keep advising Bjelke-Petersen to give shorter answers.

“I told him that if he wanted to be a successful politician he had to stop talking like a lay preacher,” Callaghan said.

“Politics is all about headlines,” he told Bjelke-Petersen, “so you have to be short, sharp, clear, and uncomplicated … and never pretend you are what you’re not!”

When the Premier kept straying onto national politics, Callaghan came up with one of his best political one-liners: “Mr Premier … there are no votes south of Coolangatta.”

Once he got to know the Premier, Callaghan advised him not to put so much effort into long speeches in the House of Parliament: “You can say what you like in the House, Mr Premier, but if it doesn’t get out to the two million voters you’re wasting your breath.”

In the end, Bjelke-Petersen hired Allen Callaghan as his tactician and image restorer.

Thus did I end up with a job at the ABC.

Callaghan was a perfect fit for a Premier whose party received only 19% of the vote and had thus been under attack from all sides.

As an experienced and aggressive journalist, Callaghan was not in the tradition of the ornamental PR front man. Instead, he would use a swift deflating remark on reporters who maligned his boss – followed by a diplomatic smile, and a long lunch.

It quickly worked.

As Bjelke-Petersen’s fortunes turned around, Callaghan began to receive calls from journalists all over the country demanding answers.

“Vee shall hask the Kwestions,” Callaghan would say in his best Nazi accent.

When he picked up his phone anticipating yet another keen journalist, Callaghan would say: “Speak … it’s your 10 cents.”

Sydney and Melbourne journalists – expecting an apologist for Australia’s most rural and conservative leader – were surprised when sometimes, even before they spoke, he would say: “We deny everything!”

When a top journalist came up with a brilliant difficult question and waited smugly, Callaghan stayed quiet and then looked up and said: “What do you want? A medal?”

I asked him one day why he acted in this way … and if it was good for business.

He replied: “Old Chinese saying … When the Dragon smiles, he shows his teeth.”

Unlike his boss, Callaghan was a gregarious character who was at ease in the company of journalists, artists, and corporations.

While Joh read the Bible, Callaghan expanded his education by reading voraciously and widely.

From Churchill he said he learned “the art of the simple message”; from Gandhi “the moral influence”; from Machiavelli “the theory of politics”; from Marx that “politics is about people”.

Goebbels, he told me, was “the first to understand the use of radio for mass persuasion and its misuse for propaganda”.

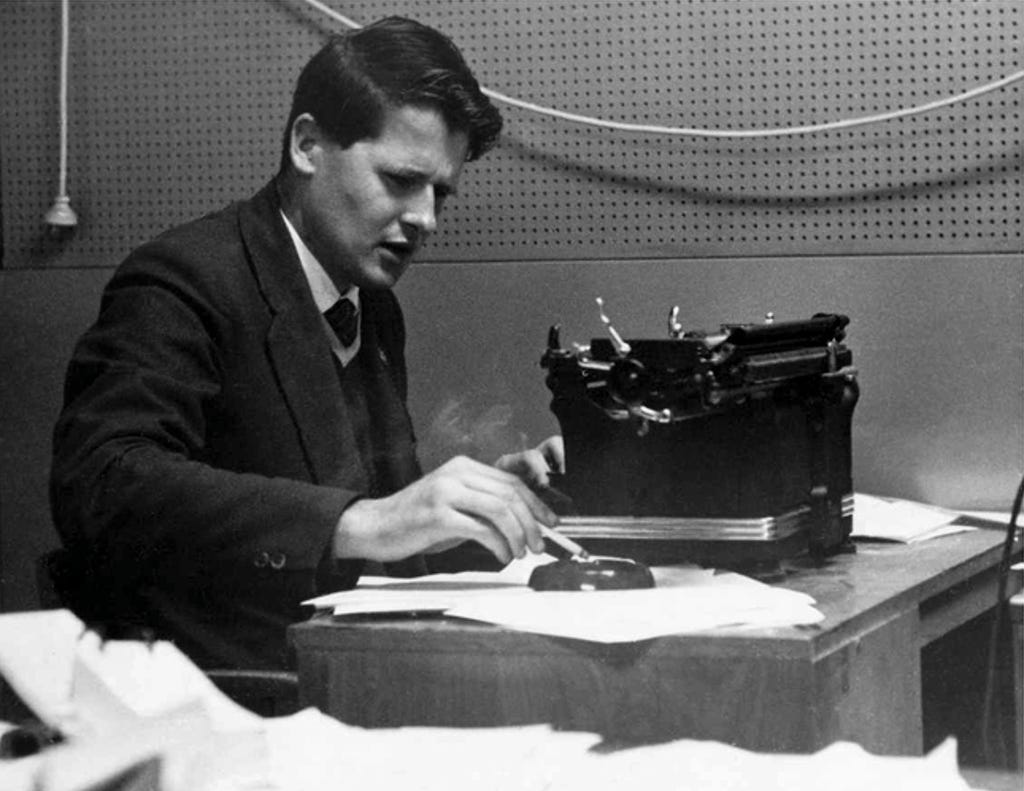

Callaghan also contrasted sharply in dress and style with the traditional Australian PR man.

A Sydney journalist noticed this and reported: “Bjelke-Petersen is surrounded by rangy six-foot Queenslanders in straight suits” – a description that fitted Callaghan as if tailor-made.

No leather jackets for Callaghan; no fashionable platform shoes; no flared trousers; no long hair.

Callaghan concentrated on flair and style at his typewriter … writing press releases and speeches for the Premier who soon became the most successful politician in Australia.

For a man with such a demanding job, Callaghan always seemed cheerful. And the happier he was, the more he would put on a jokey accent.

“Ah so, comrade” he would say, or “Vee have vays of dealing vis you”.

Some of his one-liners were outlandish, but as well as reflecting the views of the Premier’s Country Party they always contained a kernel of underlying truth.

When some Queenslanders wanted the state to secede from the Commonwealth of Australia, I knew it could never happen, but Allen replied: “Nothing secedes like success”.

When an interviewer asked him why the Bjelke-Petersen government was the most conservative by a country mile, Callaghan replied cutely, “Queensland bananas bend to the right”.

When Queensland’s lack of national parks made headlines, Allen told a journalist: “Did you hear our new national parks policy? … North of Cairns we start protecting people!”

He was fond of saying that everyone wanted crocodiles on Cape York protected … “until the crocs start surfing into the beach at Surfers Paradise”.

Three years after Callaghan joined him, the Bjelke-Petersen-led Coalition wiped out the opposition Labor Party with an Australian record swing to the government of 16.5%.

After that, the Labor Party started to see Callaghan as the Machiavelli of Queensland politics.

Labor Party leader Perc Tucker said the Premier was being “propped up by speechwriters and public relations men”.

Even the Labor Party’s Prime Minister of Australia, Gough Whitlam, acknowledged Callaghan’s influence – but in his own erudite way.

Whitlam told a 1974 press club lunch in Brisbane:

“I have, of course, some idea of just now coherent and articulate the Queensland Premier is … I suppose you see the hand of Jacob in the paw of Esau.”

We reporters all looked at each other in bewilderment. It took Allen Callaghan to explain the reference.

In the Bible, Esau and Jacob were the sons of Isaac.

Isaac, old and blind, planned to bless his older son, Esau, and leave him his kingdom. But – while Esau was away – Jacob pretended he was Esau and, to fool his father, covered the back of his hands with goat skin.

When Isaac asked if he were Esau, Jacob answered “yes”.

Isaac reached out and felt his hand to see if it was hairy … then declared:

The hands are the hands of Esau, but the voice is the voice of Jacob.

Whitlam was saying that Bjelke-Petersen was speaking with someone else’s voice – Allen Callaghan’s.

After that record-breaking election win, journalists from all over Australia began to take the Flying Peanut seriously.

And their editors all demanded interviews.

Particularly about the infamous Queensland gerrymander which kept the Premier in power and had become so blatant that it was known throughout Australia as “the Bjelkemander”.

In those days, Mike Willesee was the most famous interviewer in Australia via his national TV programme, and he was clearly not impressed with Bjelke-Petersen. However, TV needs controversial interviews to attract ratings … so his office kept ringing Callaghan trying to arrange one.

But Callaghan didn’t want the Premier exposed to a Willesee interrogation .

I was in Callaghan’s office when Willesee himself finally rang to ask about the gerrymander.

“It’s in the basement with the crocodiles,” Callaghan told him.

Talking over Willesee’s objections, Callaghan added: “We feed the gerrymander at 3 pm … if you’d like to be there.”

Callaghan knew that producers, reporters, and editors had to have stories that others didn’t. So – as controller of Bjelke-Petersen interviews – he was in a powerful bargaining position.

And, the more famous Bjelke-Petersen became, the better the tactic worked.

A political journalist who could not get an interview with a Premier or Prime Minister during major moments risked credibility, reputation, and job.

To reporters who “transgressed” after being granted access, Callaghan would half-jokingly promise to send them as “Press Attache to the lower Slobovian Embassy,” adding “Vee hav vayhs of dealing vith you.”

Callaghan told me his power grew from the fact that “Governments make news; Oppositions give views”.

Once, when he took a Sydney journalist to lunch, the man asked a question about the vast disparities in electorate numbers in Queensland.

Callaghan turned immediately to the waiter and said: “Separate cheques please, waiter”.

Journalists and political press secretaries end up in a symbiotic relationship – like a waltz – where they need each other to perform: but with opposite aims (one steps back with the right foot while the other steps forward with the left).

I occasionally felt the edge of Callaghan’s tongue: but, perhaps because of our time together at the ABC, only mildly.

One day, Callaghan told me he’d started out as a telegram boy after his family moved to Coolangatta from Brisbane, and, aged 15, then worked at a Gold Coast sand mine ... before getting a journalism cadetship on the Daily News in Murwillumbah.

I commented that sand-mining experience would be essential to get a job in the pro-mining Bjelke-Petersen government.

He replied: “Ven zee storm troopers come. Ven zay knock on your door, I vill tell zem to smile.”

It was Callaghan’s one-sided commitment to his boss that prevented us becoming what you might call friends: though we were necessarily in regular contact … for our own benefit.

For example, in 1980 Callaghan unexpectedly appeared at my front door for the first time. When I greeted him he didn’t say anything – just brushed me aside and walked straight through my house and sat down at my typewriter, inserted a piece of paper, and started typing.

Then, without saying a word, he left the way he came in.

He had typed:

Flo Bjelke-Petersen will head the Party’s Senate ticket at the next election.

I had a national scoop … the Premier’s wife would put the Bjelke-Petersen name at the top of the party’s Senate ticket thus taking a vital Senate seat off its Coalition Liberal partner.

And Callaghan had … let me know that it was his own brilliant idea.

As well as devising such political tactics, Callaghan also provided his boss with sharp retorts to use against political opponents ... “death adder unions – they strike first”; “when you go to the unemployment office, tell ’em Gough sent you”; “Help Tom Burns fight air pollution: give him a gag”.

When Prime Minister Whitlam went to Athens, Callaghan fed the Premier: “If he wants to inspect ruins he should come home and look at the economy.”

When Bjelke-Petersen was criticised for being a poor speaker, Callaghan retorted: “Fast smooth-talking is for toastmasters and confidence men”.

I saw their doubles partnership in action on a freezing windy pre-dawn morning on a Canberra airfield.

Because of fog, the Premier’s light aircraft had at the last minute been denied permission to take off, so we retreated into a one-room aero-club shed on the outskirts of the airport for warmth.

No one knew we were there.

A large black telephone on the mantel-piece rang, and the Premier, who always answered his own phone at home, picked it up with his usual: “Huh-huh-huh Hello? Joh Bjelke-Petersen speaking.”

I was seated talking to Callaghan when the Premier swung around in a panic, his hand over the mouthpiece. “Allen! It’s the Brisbane Telegraph! They want to know what I thought of the Federal Budget!”

Allen never even hesitated.

He looked up and said: “It’s a Sydney-Melbourne Budget, Chief.” The Telegraph had their headline. The Premier had his front page.

Still, Callaghan was careful to deny that the Premier needed him.

“I propose, he diagnoses,” he told me.

“I see myself as the sort of servant the Egyptian pharaohs used to have – a vizier rekhmire, the eyes and ears of the pharaohs. But the pharaohs were still the pharaohs.

“People see me as an evil genius directing the Premier. But if I dropped dead tomorrow he would continue to be successful. He just lacked experience facing the media. You can put silver eye shadow on, blow-wave their hair, but if the man doesn’t have the ability then nothing will save him.”

Some began to say Callaghan had become the most powerful figure in Queensland, while he modestly claimed to be “a humble mechanic”.

But such men are often also engineers.

“I’m just the mechanic in the pits, but Joh is the man who has to get out there and race. He is the Fangio.”

In 1980 I was surprised to hear the news that Allen had left the Premier’s side: he told me later: “Old Chinese saying: Absolute power lasts only 10 years.”

But Callaghan was extremely well rewarded by Bjelke-Petersen for his efforts: the Premier appointed him permanent head of the Queensland Department of Tourism, National Parks, Sport, and the Arts.

It would be an understatement to say this put a lot of public service noses out of joint: to see the father of six, the former Gold Coast telegram boy who’d left school at 15, make it to the very top without even doing a public service exam.

Because of his closeness to the Premier – and the unusual manner in which he had leap-frogged the top civil servants – he became the most sought-after permanent head in the state … and also the most watched.

In 1986, Allen Callaghan was charged with misappropriating government money: including bills for meals, for clothes, and for jewellery.

He invited my wife and me to his Toowong verandah for a Sunday lunch where I fully expected he would say the charges were all trumped up.

But those deep-set blue eyes squinted even more than usual as he said: “If you make a mistake you have to pay for it. I will use my time productively in jail. I will suffer. It’s not going to be easy.”

As we were leaving, Allen whispered to my wife Helen: “Don’t allow Hugh to get too big-headed”.

In court he pleaded guilty to misappropriating $43,574 from the State Film Corporation and was sentenced to four years in the clink.

Suddenly he’d lost his job, his position, his house, his reputation … and his freedom.

So when he rang at 6 am that 1987 morning and said “the crucifixion will be a little early this year” I concluded he felt his meteoric rise to the top had made him a marked man.

As The Courier-Mail’s long-time political writer Peter Trundle wrote of Callaghan’s court appearance:

“His ideas changed the state … the Premier’s voice and his were one and the same … to many public servants Callaghan’s wishes were commands.”

Allen wrote me a couple of hand-written stamped letters from jail over the next two years before he was released.

At first he’d been worried that his connection with the adored and reviled Bjelke-Petersen would see him bashed in the shower by some of the large weight-lifting tattooed inmates.

But when they realised Callaghan could churn out on his typewriter very persuasive applications for parole, they queued up at his cell.

There are terrifyingly awful aspects to being locked up which we outsiders never think of and that never make it into films.

After his fall from grace – and before being carted off to prison – Callaghan and his second wife, Judith, had rented an old oiled-timber railway workers cottage on the Ipswich line next to a station.

While he was in jail – even though their neighbour kept a close watch on the house – it was broken into 13 times!

Once, the thief took Allen’s suits.

Another time, some kitchen saucepans.

Judith, a severe asthmatic, was rightly frightened and Allen regretted that he couldn’t help her.

Eventually, police arrested the helpful neighbour who had helped alright: helped himself to items to sell at markets.

When Callaghan got out at the age of 49, he told me that – despite his proven PR record – he couldn’t get a job using that talent.

Meanwhile he and Judith split up.

Rejected by numerous large companies, he eventually became State Manager for the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA).

A “Nasho” himself, Callaghan became active in the National Servicemen's Association where he served as Secretary for the Brisbane East Branch, Editor of the Nasho News, and National Media Officer.

(The “Nashos” is a co-operative representing the 280,000 18 and 20-year-old men who were conscripted for military service between 1951 and 1972. Of these, 212 were killed on active service in Borneo and Vietnam.)

Thus every year Allen did TV commentary for the Brisbane ANZAC Day Parade.

Callaghan’s skills played an important role in the awarding of the Anniversary of National Service 1951-1972 Medal and the National Service Memorial at the Australian War Memorial.

Allen Callaghan died three years ago – on 3 January, 2022 – but although I’m a keen follower of the media, I only heard the news a few months ago – from my brother-in-law – that Allen hadn’t appeared at the annual Parade.

He did once warn me:

“Monsieur, our good deeds are written on water”.

A good comment on the Callaghan story from an editor in London:

"Allen Callaghan - a rare talent who would have made a fortune in Hollywood or Washington DC but who, as a Queenslander down to his bootstraps, would no doubt have considered that a sellout. Hugh brings out that side of his character brilliantly and I loved the gags especially the one about feeding the gerrymander. "

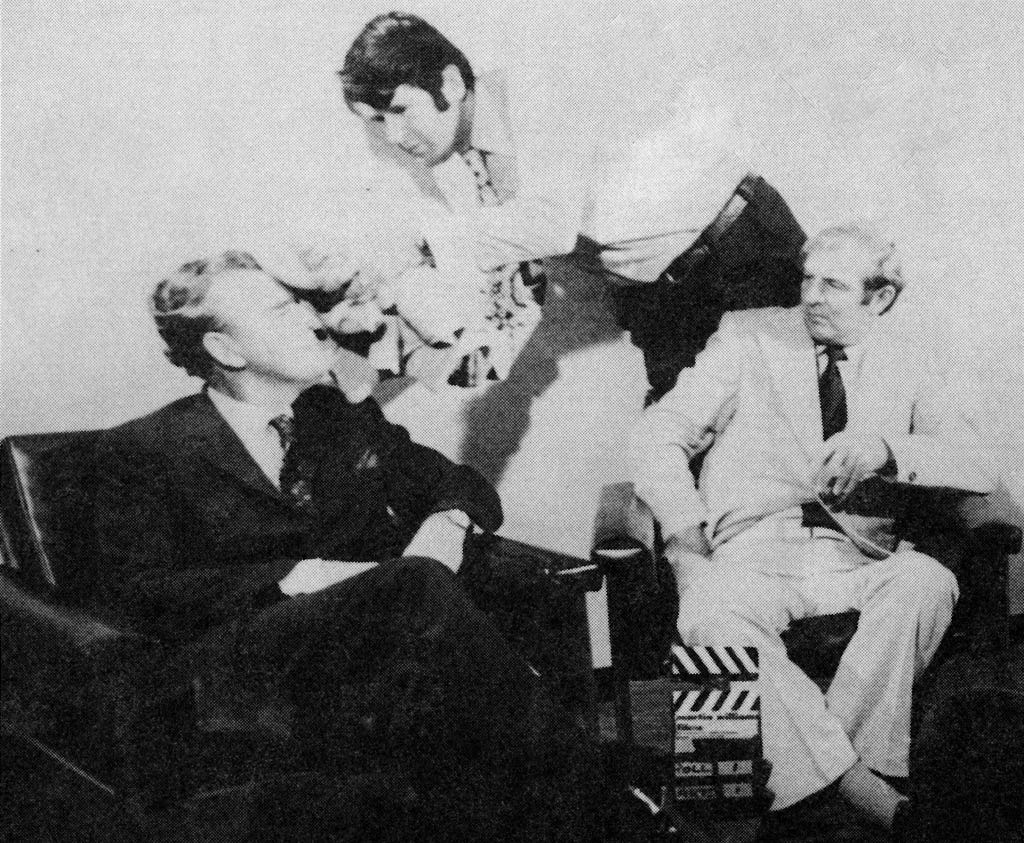

This is a very nice piece thanks Hugh. I see you put to use a couple of the pictures of Dad that I used in his Courier Mail Tribute. I've also pinched the one in your post of you and Dad that I hadn't seen before. All the best, Dianne Callaghan.