The first time I saw him, he was sitting by himself in the crowded Palms Café in the foyer of the overly ornate Regent Theatre in the centre of Brisbane.

It was the 1950s so he was delicately using an elongated teaspoon to stir the ice cream into his Sarsaparilla Spider.

Although only 17, he already had the solid build and tanned muscles of an adult. This – together with his large round Chinese-Mongolian face and thick head of jet black hair swept straight back – made him look fierce.

Like an ancient warrior.

Which was appropriate, since he came from the tropical jungle town of Innisfail at the junction of the crocodile-infested North and South Johnstone Rivers — 1,000 miles to the north.

Because of his unusual name – Billy Lee Long – and the fact he was fourth-generation Chinese Australian, I was expecting him to be a bit different.

But nowhere near as unconventional as he turned out.

Billy Lee Long was my mate Kenny Fletcher’s best tennis pal: that’s why Fletch had brought me into town to meet him. I thought I’d never see Billy again but – as it transpired – we three were to remain friends for the rest of our lives: interconnecting at nearly every turn, sometimes many years apart.

Australian Davis Cup Coach Harry Hopman was hugely successful in the 1960s because in the 1950s he drag-netted Australia for athletic young tennis players and put them in his Harry Hopman Tennis Squads.

Billy was in Brisbane as part of the Squad: Hopman, from 2,000 miles away in Melbourne, had heard of his athleticism.

In that same group of teenagers was a red-headed boy who to me looked like a chewed-up piece of string. This was Rod Laver who’d come all the way from Rockhampton, 500 miles north of Brisbane.

(Laver is now still the only man to win two Grand Slams, i.e. winning the Australian Open, the French Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open in the same calendar year.)

Plus, Hopman had selected a reed-thin cupid-lipped blond boy, my mate Kenny Fletcher, from the working-class southern suburbs of Brisbane. Fletch was to become one of only 11 players ever to win a Grand Slam – still the only Grand Slam ever in Mixed Doubles — in 1963 with Margaret Smith (Court).

Like Billy-O

Billy Lee Long was the outstanding athlete in that squad. And he could do things with the white tennis ball none of the others could – cutting and slicing the nap sideways, up, under, and around, in mesmerizing fashion. He volleyed winners behind his back just for the fun of it; occasionally served underarm so the ball spun violently (but legally) sideways away from his startled opponent; or swung his serve so much it would disappear out the side gate.

And always with his large hands gently holding the racquet-handle, the fingers almost elegantly poised.

Fletch admired this eccentricity in Billy because he himself had been heavily coached by experts in the correct way to play tennis. Yet here was Billy acting the goat … defying the golden rules of Hopman, and gravity, on court.

Always testing the absolute limits of cat gut on nap.

At the same time, Billy – from a tight-knit, reserved Chinese family in a remote town – loved watching brash city-slicker Fletch swear loudly and ignore authority figures who told him what to do: always cutting corners in training, skiving off to the pictures, constantly looking for ways to escape supervision.

I guess that’s what brought the two together, and kept them close for a lifetime: the fascination that your best friend could be so unlike yourself.

Impatient Fletch fretted every time Billy told him to ignore the ring of a telephone. Billy would hold him back, saying, “Wait, Ken. Let it ring for a while … now very slowly stand up and walk over and answer it”. Billy wondered why Ken wouldn’t fully exploit the gift God gave him of uncanny hand-eye co-ordination by getting fit.

Or at least develop some muscles.

Billy insisted the strongest player won the fifth set; while Fletch believed trick shots in the midst of matches were fraught with disaster. “The trouble with Billy,” Ken told me once, using his penchant for gross exaggeration, “is that on a big point he’s likely to turn around and serve into the grandstand!”

In the end, Rod Laver and Fletch stuck with tennis, but Billy – once out of sight and out of mind back in Far North Queensland – turned to other sports … and proved master of them all.

His whole life became one of running, jumping, hitting, diving, swimming, and competing non-stop.

Thus he always dressed in shorts, a T-shirt, and bare feet.

It was only after the Hopman Squad presented him with his first pair of tennis shoes, aged 15, that he added shoes to his wardrobe.

In 1955 Slazengers sent Kenny Fletcher to Townsville to promote their racquets by winning the North Queensland championship — where, although only just turned 15, he beat the Australian Armed Forces champion Darryl Picton in the final.

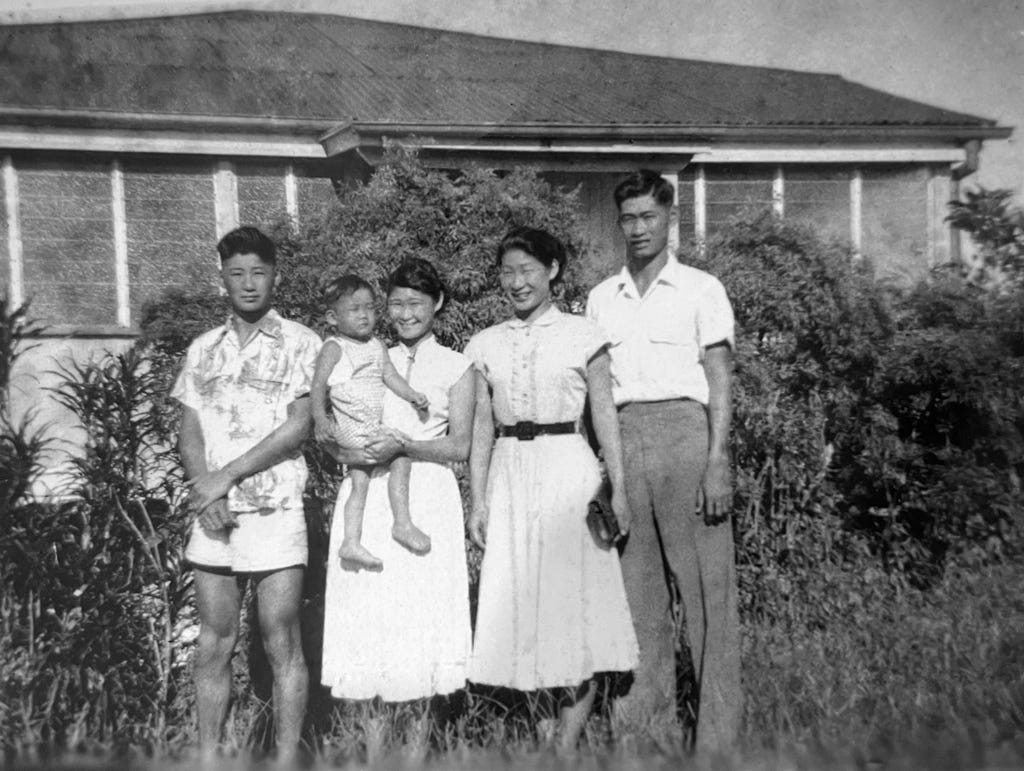

Kenny stayed on with the Lee Longs in their home in Innisfail where he had fun taking Billy’s nephew Graeme King Koi on piggyback rides, just as only-child Kenny as a toddler had enjoyed piggyback rides with his aunt and cousin. Ken took the photo below of Billy and his siblings with his sister Ros holding her son Graeme.

In later years Kenny would always ask Billy, “How is my little champion, Graeme? How old is he now?”

In 1958 Billy moved to Cairns and opened a branch of his father’s Bill Lee Long Sports Store. Then in 1960 he built squash courts across the road.

1960 was the year that Fletch — despite having reached the last 32 at 1959 Wimbledon at his first attempt aged 18 — was left out of the touring Australian team for throwing his racquet over the fence during a match in the Australian Open.

Slazengers took this opportunity to send Ken on a tennis tour of the Queensland coast all the way up to Cairns, where once again he was welcomed into the Lee Long family: this time staying for a month.

Instead of playing on the Wimbledon grass and the Parisian clay, Fletch was challenged by all the 18-30-year-old tennis players of the north. Billy today still nearly blushes when he quotes Ken as saying: “I will give anyone of you five games start and the serve. If you can win a set, I will walk to the Nurses’ Quarters in my jockstrap — but if I win you have to shout Billy and me lunch and a beer.”

Billy said that when news of the bet swept through Cairns, some nurses turned up to cheer Ken’s opponents: “Everyone wanted to see Ken forced to drop his dacks and walk across the road to the Nurses’ Quarters.”

For the whole four weeks Billy and Ken ate lunch for nothing.

Billy Can

As a boy, Billy learned to swim in the North and South Johnstone rivers and became one of the three or four fastest swimmers in the state: he had to swim fast because of the crocodiles. This ability soon lured him into the waters of the adjacent Great Barrier Reef: diving and spear-fishing with his sister Fern ... camping on deserted islands and coral cays.

So it was only natural, when he was 18, that Billy joined the Etty Bay Lifesavers, swimming every day. Not only was he the fastest swimmer, but he easily won all the beach-sprinting competitions – despite, or because of, the extra effort required to run through sand.

A professional sprinter who saw him urged Billy to take up athletics and run in the rich national race, the Stawell Gift, in Victoria.

But that was a sprint too far away.

Instead, in 1960 Billy – with no spikes or starting blocks – entered the Hector Hogan Memorial 100 yards which commemorated the great Queensland sprinter who had won the bronze medal at the Olympics in 1956 but had died young just four years later.

When he won the race, Billy was presented with the prize — a canteen of cutlery — by Hector Hogan’s father. Mr and Mrs Hogan were so taken with Billy that they flew him down to Brisbane for a month’s holiday at their house at Nudgee Beach in Brisbane. “They treated me as though I was Hector,” Billy recalled last week.

Billy’s father – “Old Bill” – owned a sports store overflowing with gear, so the closest Billy got to tennis for the three years after returning from the Hopman Squad was re-stringing racquets by hand in the shop using a pair of plyers.

After hours, he could use all the equipment for nothing.

So he took up pistol shooting with his sister Fern and the pair started a Water-Skiing Club and a Big Game Fishing Club. Then one day Billy borrowed a set of golf clubs from the shop … and soon was playing off a handicap of one. Once again it never crossed Billy’s mind, or personality, to leave Cape York and go on the professional golf circuit. Instead, he coached others for nothing … and specialised in trick shots: showing the many different things a golf ball could be made to do.

One day when I was with him visiting a farm in Mareeba, west of Cairns, Billy borrowed a club and a ball from the house and took me outside.

I wondered what was going on.

He dropped the dimpled white ball in the thick farm grass and pointed at a banana tree 200 yards away and said: “Hughie, the object of golf is to land the ball at the base of that banana tree.”

Crack!

He did exactly that – but I declined to have a go at the impossible. So he took me for a swim in the giant Tinaroo Dam: a sea of deep cool dark mountain jungle water where we were the only humans. The only problem was that I was booked on the last plane out of Cairns and we were running late.

“Stop worrying,” Billy assured me as he detoured to show me a quarry he was interested in. “You’ll give yourself an ulcer.”

I missed the plane and had to stay an extra day.

Billy loved teaching people who did not have his natural gifts to play golf, or tennis, or even squash – he was also North Queensland squash champion. (Fern was the women’s champion.)

One day in Cairns, I watched him coach kids who’d never played tennis before.

As they rushed to pick up a racquet, Billy gently told them to put the racquets down on the ground. “I want you to first learn to play with your hand.” Then, instead of teaching them to hit umpteen shots from the back of the court after the ball had bounced, he started the kids at the net.

“Everyone can hit the ball from the back, but few can volley,” he told them. “Yet the volley is almost always a winning shot: provided you whack it like you’re trying to kill a cobra on the other side of the net!”

Standing at the net, each child lifted their open hand while stepping forward to kill the cobra.

“As you wind up, say to yourself coil…snap!” Billy advised.

To get a service to swing, he told them, “Aim the racquet away from your body and the court at the peak of the roof of that house next door”. And it worked.

Later, he addressed them about rallying from the baseline, asking: “Can you count to two?” They, of course, enthusiastically agreed.

“Good, then you can rally from the back!”

To illustrate, Billy lifted his racquet up and back as he turned side-on to meet the ball … saying “One!”

Then, swinging the racquet swiftly through the air, he stepped forward shouting “Two!”

One of those little girls, Brenda Remilton, later found her own way from Cairns to Stade Roland Garros in Paris and, though coach-less and trainer-less and in no team, reached the last 32 in the French Open singles. Brenda also played Wimbledon.

In the 1980s she was ranked in the top 100 in singles and top 20 in doubles.

When coaching, Billy also brought his insight into the human character.

In 1961, the local pharmacist, Wally Punchard, came into the Lee Long store for a tennis racquet restring. “Billy,” he pleaded, “I’ve been playing the Cairns Open for more than a decade, and I’ve never won a trophy! How about playing the doubles with me?”

“Gee Wally,” Billy replied, “The tournament is on in two weeks and I haven’t played tennis for two years.”

“Yes Billy, but I’ve been playing forever and never won! No one wants to play with me because I’m only 5 foot 3 and I’ve got a dinky serve.”

Billy was coaching Wally’s kids both tennis and squash and Wally was a regular shop customer, so it was hard to refuse. “OK,” said Billy, “I’ll play with you … but only if you promise to do one thing for me, and one thing only. Serve slower … so they will have to lift the ball to get it over the net and I will terrorise them on the net!”

Wally never lost a serve. He and Billy never lost a set. Wally got his trophy.

“I’m pleased he did,” Billy said last week, “he died last year aged 95.”

In the following decades, wherever he travelled in the world, Billy coached golf to friends and their acquaintances. Recently I asked him what advice he gave?

“Well, I say: Imagine you’ve lost your left leg and can only walk with crutches … how would you play golf?” Then he’d tell them about a friend of his father’s, Mr Creighton, who in 1966 wanted to play golf: “Even though there were no buggies in those days. Mr Creighton had no left leg, so I created a swing where he stood with the crutch under his left arm and then swung the club just with his right hand – similar to hitting a forehand in tennis. He eventually played off 12.

“So if he could do it, you can.”

After Billy won his Golf Club’s men’s title in 1972, he never again competed in a golf competition … and never became a member of a golf club anywhere in the world. He just coached friends at their clubs for fun.

He had other things on his mind.

Billy’s Goats

All the while he toyed with sport, Billy dreamed of becoming a successful entrepreneur.

As he used to say to me: “There are three types of businessman: the bad businessman, the successful businessman, and the Jewish entrepreneur … and then, of course, there’s the Chinese trader.”

Doing business was in his blood.

His great-grandfather, Dr Kwong Sue Duk, born in Canton, in 1875 was sent to Australia to be the medical doctor for 18,000 Chinese on the Palmer River goldfields at Cooktown on Cape York. He also treated the 6,000 non-Chinese.

Then, in 1880, he built a medical centre in Cavanagh Street, Darwin, and five shops (The Stone Houses) now listed as historical buildings.

After Mossman was bombed by the Japanese in 1942 all women in Far North Queensland were told to take their children inland. So Billy’s mother, Felicia, took her four to the remote tin-mining town of Irving Bank where the three older children went to the one-teacher school.

Bored at home alone, four-year-old Billy started rounding up wild goats from a hill behind the house: milking them and selling the milk to a woman who turned it into cheese.

He began with 10 goats. “In the end I would bang on the corrugated-iron wall of the dunny and 40 goats would come down to get a feed.”

Soon he was selling the kids.

In 1943, the family returned to their home at 14 Owen Street, Innisfail, next door to the Chinese Joss House temple. Soon Billy — known as “Billy Boy” by the family —was posing in front of the temple for American servicemen to photograph.

“They would then give me a coin — sometimes silver, sometimes gold,” Billy remembered last week.

Innisfail was sometimes sheltering up to five ships and a thousand sailors. So they needed something to do. The American in charge, Commander Hobbs, found a fellow tennis enthusiast in Old Bill, who was the Far North Queensland (FNQ) men’s champion.

And in no time every tennis court had been commandeered for naval-civilian matches, including the Lee Long’s backyard grass court and the lit court next to the Nurse’s Quarters.

Puffing Billy

Always wearing bare feet because of the heat and heavy tropical rain, Billy in school hours earned the nickname “Dreamy” because he was more interested in planning other things.

But this didn’t stop him becoming captain of the school and the football, cricket, and athletic teams.

Soon Billy won the FNQ Under-10 tennis title in Cairns, so Slazengers presented him with two brand-new racquets and asked the Tennis Association to pay Billy’s train fare 1,000 miles south to Brisbane to compete in the State Age Titles.

This train was known as Puffing Billy because coal was fed into the old steam engine which would take three days and two nights to make the journey. Felicia handed Billy a paper-bag filled with sandwiches and fruit and told her 10-year-old: “Don’t get off that train until the other end! Your Aunty Gertrude will meet you.”

Billy didn’t know where “the other end” was, and had never met Aunty Gertrude. He had his two racquets but no shoes “as everyone in those days after the War was too poor”.

When he arrived, he worried that his aunt wouldn’t recognise him because he was covered in black coal soot.

That was Billy’s first ride on a train, and soon he was on his first tram ride to Brisbane’s imposing City Hall. “Before we changed trams to Kalinga, my aunt said ‘Billy, remember that City Hall, because tomorrow morning when you get to this Tram Stop, you must change trams and catch the Toowong tram. Get off at Milton which is the next stop after the building with the four big X’s on top.’”

Next day, as he walked into Milton Tennis Centre for the first time, Billy Lee Long was surprised to see five old men dressed in long white trousers, long-sleeved white shirts, white shoes, and white broad-brimmed hats.

These were the tennis coaches gathered to teach the best children in the State: Mr Vince Kelly, Mr Jack Grinstead, Mr Jack Pile, Mr Gar Moon, and Mr Ian Cowie.

Barefoot Billy’s world had changed.

The first person he spoke to was a young blond, white-skinned Brisbane Catholic boy called Ken Fletcher who became his best friend for the rest of his life. They phoned each other every morning and Felicia would shout, “Billy Boy, your little brother’s on the phone”.

Next week: Billy On the Boil

What a complex character your Billy is. He and his mate Kenny do share something: an unwillingness to conform to the standard behaviour. I can't work him out. He competes. Therefore he presumably wants to win, to beat others. Yet seems to hold the victories very light, and moves on to another venture for the pleasure of learning how to do it. Perhaps loyalty to family is more important to Billy. And that's what anchored him? Hoping part 2 will reveal the solution to this enigma. In any case, it's a revealing story which also tells me a lot about life for some Australians during world war ii.

Thanks, Hugh. I am going to try to get my grandkids to work on the Fletch business during the school holidays.