In the dining room on the top floor of Peking’s only hotel for foreigners I felt out of place … seated as I was among a score of well-dressed Europeans, none of whom spoke English.

After days of travelling through China on trains from Hong Kong in May 1965 I was unshaven, owned no jacket, and wore a plastic black money belt buckled securely round my waist.

I felt a bit better when I noticed one other eccentric: tall enough to stand out and obviously not in Peking to sell or buy like these businessmen.

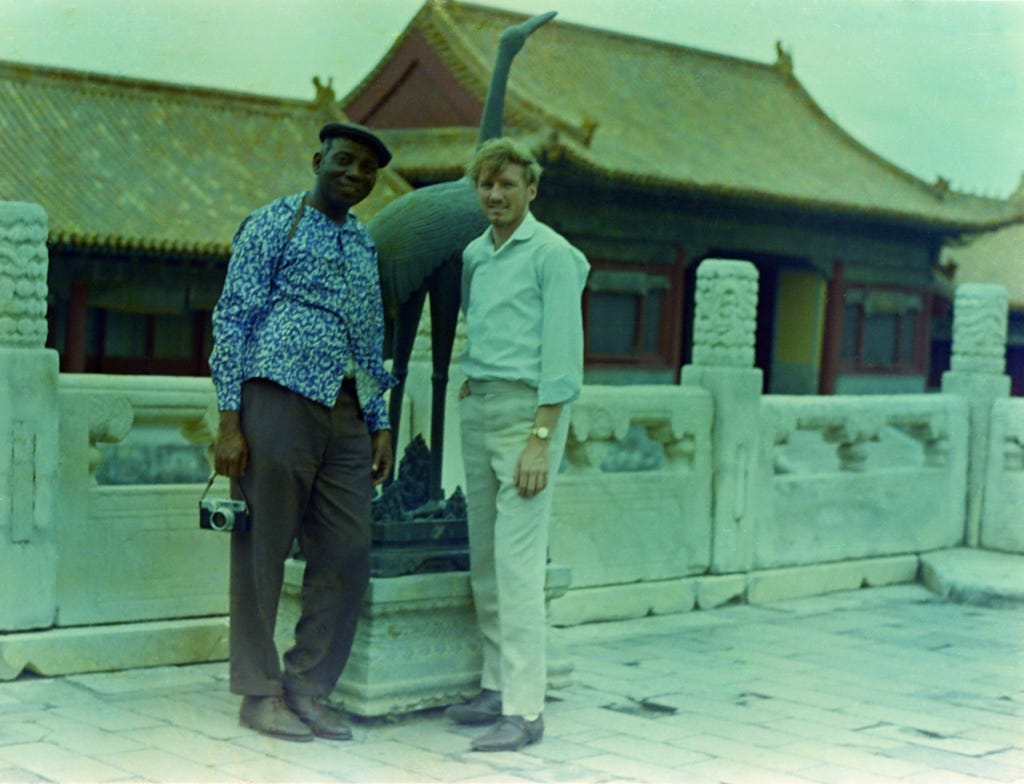

He wore a cloth cap and, instead of a suit and tie, a lairy multi-coloured shirt with painted orange hibiscus flowers all the way down his long, long sleeves.

We were the only two who dined alone.

However that wasn’t why I noticed him: he was black. I hadn’t expected to see any African men inside the closed borders of post-colonial China.

What was he doing here?

I watched him finish dinner and enter a room next to the bar. There he walked around and around looking down all the time.

What was he doing there?

Turned out he was playing snooker all by himself.

My pastrycook father, Fred, had taught me to play snooker in the Irish Club in Elizabeth Street, Brisbane, so I leaned against the doorway observing this African’s form.

He was unlikely ever to finish a game: he didn’t bend low enough over the cue to sink many balls. But it was pleasant to watch his large frame slide silently and quickly backwards and forwards around the table as if he were on roller skates.

He was like a tall, black version of Minnesota Fats in The Hustler.

It isn’t much fun playing snooker alone so — not hopeful that he spoke English — I asked if he wanted a game.

A light turned on inside his head.

“That would be absolutely, truly delightful, stranger,” he said, in suspiciously perfect Queen’s English … sticking out a long, soft, smooth hand that completely enveloped my white one. “I have become far too dedicated to seclusion here in Peking. And tell me, my friend, where might you be from? And to whom do you report?”

He was as English as you could get, and his name was even the same as our late King’s: full name George Kitson Mills.

George said he was from “somewhere west of Suez”.

“Actually, to be more precise, I hail from James Town, Accra, in Ghana. That’s north-west Africa to you. By way of an unwise and an untimely decision, I have been ensconced in China for nine months since.”

I told him I too had left my homeland many months ago, so I knew what he was going through.

George lived fulltime in this international hotel: which meant he was ultra important, and well paid. But by whom?

How come he spoke such good English?

“I have travelled expensively,” he said, laughing at his own play-on-words. “But really Hugo, English is the main language spoken in Ghana and taught in our schools, since my country was a British Colony for nigh on 90 years.”

“You did better than us,” I said. “We were a British Colony for more than a century.”

I had to admit to George that I’d never heard of Ghana.

“Methinks that’s not surprising,” he said, accidentally sinking a red in-off the blue. “Until eight years ago my country was called the Colony of Gold Coast.”

“So you’re from the Gold Coast?” I said. “Well, George, so am I! My mother, Olive, was from the Gold Coast in Australia. It used to be called the South Coast, but soon after you changed your name from Gold Coast, we changed ours to Gold Coast. So we must have taken the name from you.”

“Your tale, Hugo, would cure deafness,” said George in astonishment as he missed the brown. “A most auspicious star! It has been otherwise ordained that you and my crying self are countrymen.”

And we shook hands again as if we had been friends all of our lives.

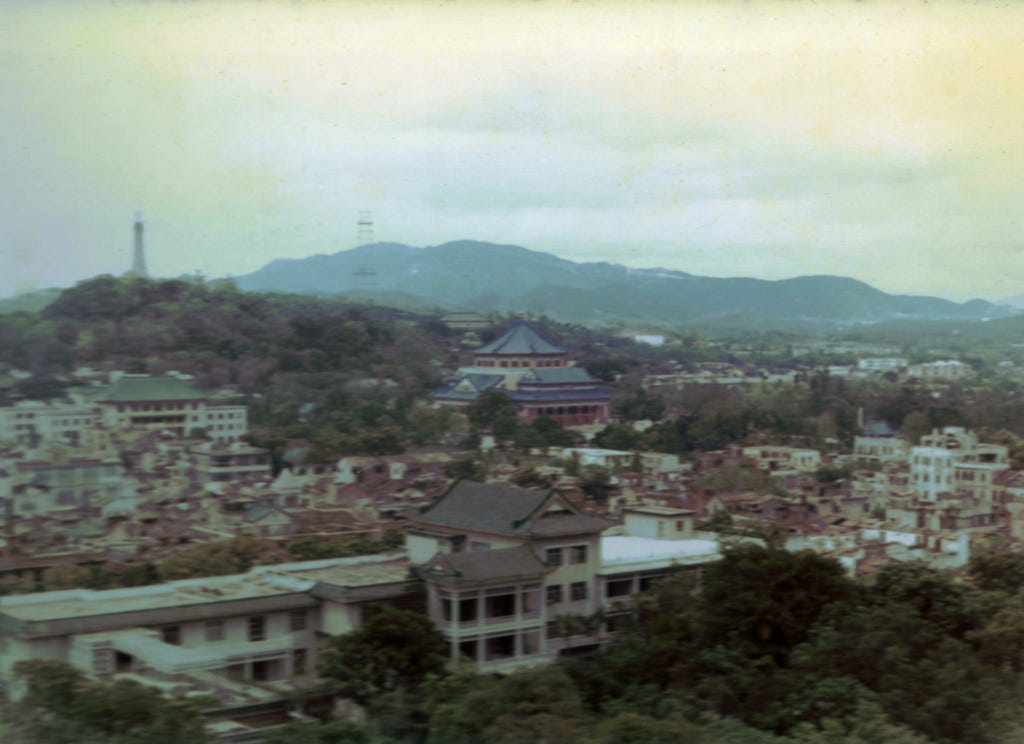

So I showed George some pictures I’d taken of the southern Chinese capital of Canton — known as “Goat Town”. I was surprised at the lack of trees among the bricks.

George didn’t know much about Australia, except that it was a place to which Britain had shipped convicts, and that he couldn’t live there because he was black.

“It is my bountiful misfortune to be banished from that magical isle,” was how he put it.

“We Aussies like to ban things,” I told him. “My English boss in Hong Kong, Max Schofield, reckons Australia bans everything because we’re afraid of being tempted back into committing the sins and crimes of our convict ancestors.”

George was more interested in the fact that I was a journalist than an Australian.

“Journalists can go where fancy leads. But they must avoid falsehoods and crediting lies,” he warned. “Wherefore I will help you in Peking. But, since you are a journalist, it could be difficult, and we needs must be discreet.”

But George wouldn’t reveal what he was doing in China.

“You are the journalist, Hugo. You must make that deduction.”

“Can you give me a clue, George?”

“I already have,” he said, smiling through his large teeth, made whiter by his skin, “but you must yet see it.”

What clue had he given to his work in China?

I was getting so mixed up searching back through our conversation that – having nominated the black ball for my next shot – I discovered it wasn’t where I thought. I found myself aiming down the other end of the full-sized snooker table at nothing but the cush.

“I spy with my little eye … the blacks are both up here,” said George, standing and pointing helpfully in front of him.

Not only was the black ball up the other end, but somehow I had inadvertently snookered myself behind the pink with my previous shot.

Having given away four points by missing, I asked George why he liked playing snooker so much that he played by himself. “Forsooth, you have to eliminate the reds before you can score!” he replied, shutting his dexter eyelid. “And because the object of the game is to hide the colours from view.”

Was he an anti-Red? Or did he have something to do with the demand for Civil Rights for blacks in America?

He said not.

“In a way, Hugo,” George said, as he bent to line up a red across the wide expanse of green baize, “I am nothing but a professional liar. I have come here to the East solely to make things appear as they are not.”

Was George an English-speaking African CIA spy in Peking? Or, worse, an agent provocateur? I resolved to hold my peace, just like I faithfully promised Olive and Fletch.

After a few long games — because we had such trouble sinking all the reds — the restaurant and bar closed, and George opened up. “I suppose you could say,” George began, as he chalked his cue, “that my darker purposes are to eliminate.”

“Eliminate what?”

“Things,” he said. “Or people, if need be.”

So he was a black James Bond. But he certainly wasn’t travelling incognito. There was no way George could blend in with the crowd in Peking: not in that orange hibiscus shirt.

“Who are you working for then George?” I whispered as we stood cue to cue sharing the cube of blue chalk long since worn down to the thin red paper that surrounded it.

“By the very nature of my work,” he said behind his left palm, “only two or three people east of Suez have ever seen what I do: though most of the world would dearly love to. But that will never be. The only people to whom I divulge my secrets are a small chosen group of Red Chinese.”

“So that’s why you’re here?”

“Yes. I tell the Chinese Communists everything I know! Well, nearly everything.”

Why was he telling me all this?

“Do you steal documents, George?” I asked tentatively.

“I pray you, let us just say that on many an occasion I have conjured some document to reappear in the right place, at the right time.”

So the biggest spy in all of Red China was an African: the trouble was that, just by knowing, I was now involved.

“What happens to the people who you make disappear?”

“Oh, they bob up somewhere else later on,” he said.

Like in the ocean?

My mind was racing so fast that I had done it again. I’d nominated the blue ball, lined it up, and now it wasn’t even on the table. Yet I checked all six table pockets, but no blue anywhere.

Then I felt it.

The blue was in my left trouser pocket, and George was laughing at me.

As I looked along the snooker table he took two empty rice bowls from the bar and asked whether I knew how to solve the world’s food shortage.

He tipped the empty bowls on their sides and tapped the tops together and, as he sat them down in the middle of the snooker table, both bowls overflowed with rice – which scattered white across the dark green baize just a few yards from my eyes.

George wasn’t a spy at all.

He was a magician.

How strange, that – while other world powers were pouring money into rockets and space travel – China was paying George to teach them magic tricks!

He put down his cue and stopped to explain:

“They revere incantation in the East. To them illusion is more Confucian than confusion. Magic is not seen as an insubstantial pageant, as in the West. Here they believe in spirits, dead ancestors, and the power of sorcery. This is why the Christian missionaries failed in China.”

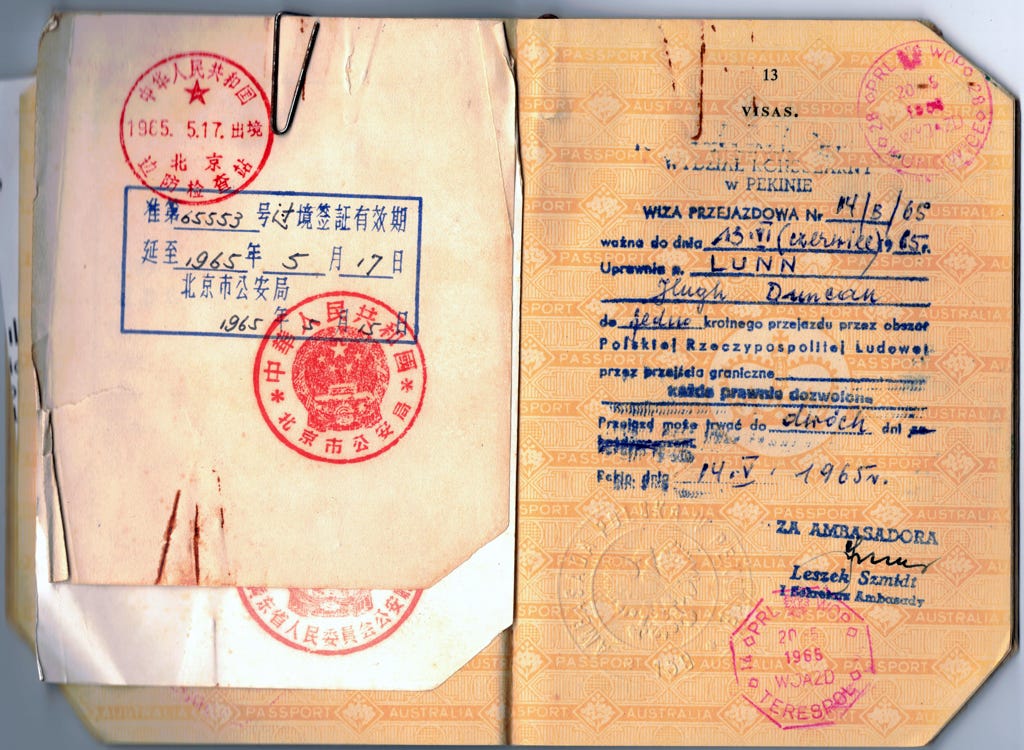

Next day, as instructed in Canton, I reported to the Peking City Ministry of Security and a second piece of shiny white paper with red Chinese chops was paper-clipped into my passport, dated May 15, 1965. It said I had to leave China by the 17th.

I was surprised how free I was in Peking as I strolled around looking for something interesting.

A crowd had gathered four deep along one side of a wall that stood alone in a street. They were reading the pages of a broadsheet Chinese newspaper, each double-page pinned up just above eye level.

Since no Western newspapers were allowed in China, I pushed through to see if I could make out what had been happening in the outside world since I’d left Hong Kong.

Just like in Australia, the newspaper had large headlines, photos, and a cartoon.

Of all things, this cartoon was of a kangaroo!

I pushed my way close enough to see that the kangaroo had some figures in its pouch, each feebly holding on to a rifle. The figures were wearing slouch hats with the side turned up, and they were peeking nervously out of the pouch: some very apprehensive Australian soldiers.

The smiling, ingenuous kangaroo was bounding happily off across a map of Southeast Asia as if not knowing that disaster lay ahead – as it island-hopped north: bouncing on New Guinea, hopping across Indonesia, springing on Singapore, skipping up through Malaya, rebounding across Thailand, onto Cambodia and into Vietnam: a country which bordered Red China.

It looked awfully like the Domino Theory in reverse.

I couldn’t read the cartoon’s caption, but I could see enough to realise that Australia had decided to send troops to fight in Vietnam.

So I was now behind enemy lines.

That afternoon over coffee in George’s room, I complained that the government official in the foyer of our hotel had prohibited me from entering the Forbidden City.

It was closed to outsiders, she said.

“The Forbidden City, by its very nature, is kept from snoopers,” George told me. “But this is most propitious. My high charms can work for you. Let me use my voodoo to break this taboo for you Hugh.”

He smiled enigmatically, adding only: “Entrance does oft depend upon enchantment.”

Next day, George took me to Gate of Heavenly Peace square (Tiananmen), the entrance to the Forbidden City in the centre of Peking – one of five ways through the otherwise impenetrable wine-red walls.

Peking had become the capital because of the protection of this imperial fortress and its moat, creating what China had called for nearly seven centuries its Middle Kingdom.

In these ancient palaces at least 20 Chinese Emperors had lived and ruled for centuries until the communists took control. It brought to mind all of those exotic words from the East: the mysterious Orient, comely concubines, emasculated eunuchs, eccentric Emperors, and meddlesome Mandarins.

It was also the building where Mao Tse-tung had hoisted the Red Flag just 16 years before — on 1 October 1949.

Once inside, I could see why it had taken a quarter of a million workers to build the Forbidden City.

There were a series of carved white marble bridges over a narrow stream passing through a huge stone-floored courtyard which led to another elevated yellow-roofed palace. Then, beyond that, another large open quadrangle; and then another elevated palace.

Each courtyard bigger than a city block.

All interior balconies and staircases were edged with white marble balustrades with intricately carved post tops. Marble staircases leading up to a palace were guarded by sculptured gold lion-like creatures as big as me. These were Qi-lins, mythical animals with huge sharp claws. To dream of one was an omen of impending success. So I stepped over the protective barrier and touched it for luck.

George took a picture.

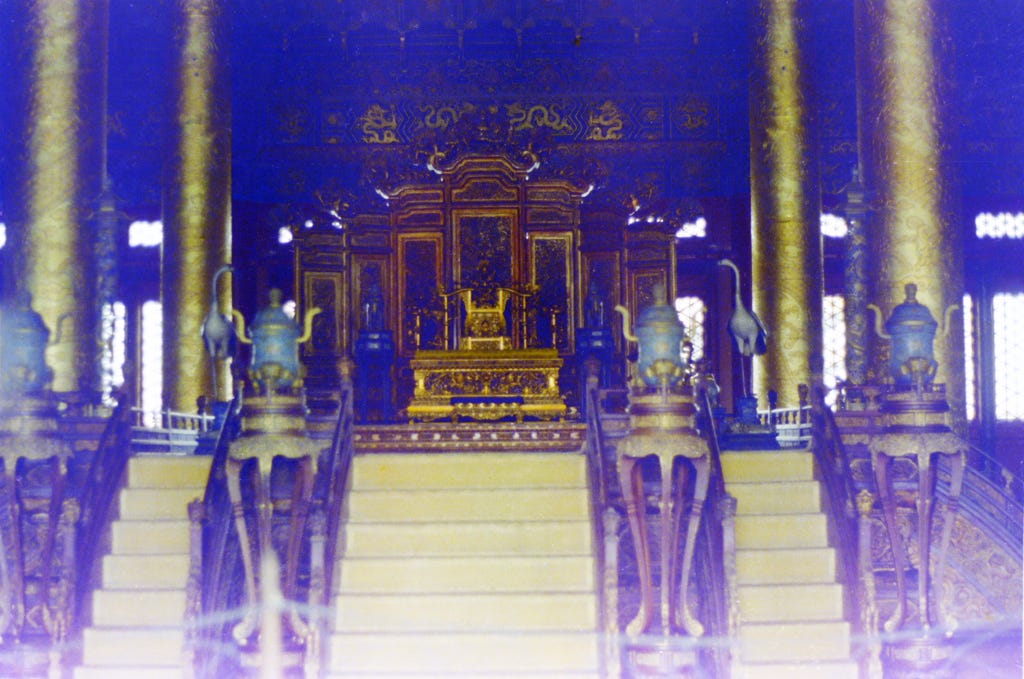

Stairs led up from the quadrangles to interior palaces with exotic names like Hall of Supreme Harmony.

In one palace, huge golden columns surrounded a wide gold throne with a carved wall behind and a footstool at the front. Here the Emperor had ruled.

What struck me most in this sea of carved dragons and gold chests – and what looked like blue teapots on curved three-legged gold stands – were the four-foot-tall lifelike long-necked cranes on either side of the throne carved out of jade.

George said cranes equalled long life for the Chinese.

This was the Dragon Throne where for centuries people had kowtowed to the Emperors who were each called Son of Heaven.

So the Emperor was like a god: the hereditary god, before the political god, Mao.

Until today, I had never seen anything that was centuries old: now I was immersed in centuries for as far as I could see in every direction.

Strangely, no one watched, or cared, as George and I wondered at the grandeur of the Emperor’s throne, looking behind and underneath his seat, and then at the carved dragons on nearby thick gold pillars.

“It is as if we are God’s spies,” said George.

Next week: How I got out.

Goodness me, that's a true adventure to enter the silent deserted Dragon Throne room unencumbered by tour leader or guide book or droning headphones. You and George were like characters in a fairy tale. I half expected a Chinese spirit or imp to materialise and challenge you with a riddle. Did George finish his job before the cultural revolution? Hope so. I don't think magic tricks were politically correct when all that took over. Your story and those photos are like an historical artefact, so much has changed. Canton now has its proper name, but I bet it isn't made of brick low-rise buildings today.

Magical!