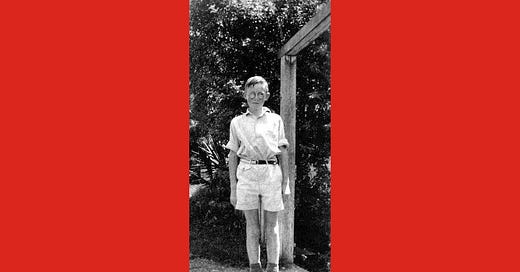

When I was 12 years old, in 1954, a new boy called Neil moved into the house next door.

My big brother Jackie and I were wary because he was a State School Kid. We had fought many of those on the way home from Mary Immaculate Convent because they didn’t like Catholics.

But, although he was tall, strong, and adventurous … this Neil was extremely mild-mannered, softly spoken, and not at all aggressive – to anyone.

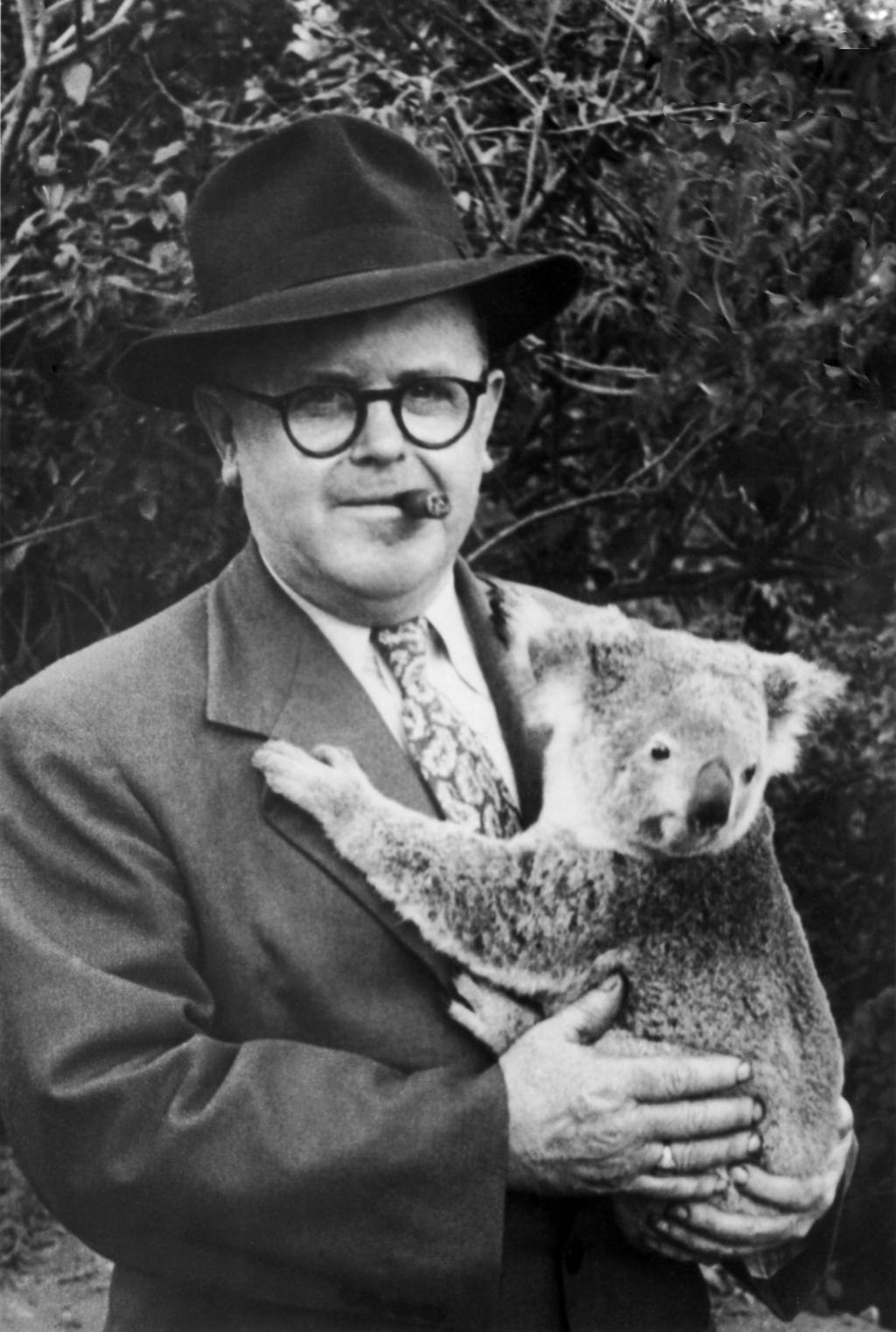

Perhaps, I thought, this was because he looked a bit of a drip in his large horn-rimmed spectacles with their Coca-Cola bottle lenses.

So maybe he couldn’t afford to put other boys offside.

I presumed his bad eyesight was why Neil hadn’t played football, or cricket, or tennis: in fact, he didn’t own any sports equipment at all. Not even a cricketer’s box to protect his balls from balls.

But, as it was to turn out, Neil was at that time busy with other activities that Jackie and I didn’t know anything about … until I perused his three-inch thick ASIO file last week.

At first, we only talked to this new boy over the falling-down slab-timber fence under our mango tree. We found out he was 16, a year older than Jackie … and in Grade 10 at Brisbane State High School.

Neil’s elderly parents were paying rent to live in the house with the lonely old curmudgeon who owned it – Mr Reeve. I didn’t like Mr Reeve because every time I played my bugle, he would lean out of his window and yell: “Cheese it, Hughie! Cheese it!” and slam the window down.

Neil’s family obviously didn’t have enough money to rent a place of their own.

Though everyone in Annerley was poor after World War II (which had finished just nine years before), no one else was living such a meagre existence as them.

Neil never went to the flicks on Saturday arvo for the Matinee like the hundreds of other Annerley kids – not even to see Doris Day or John Wayne … or even the Batman and Robin serial.

His family didn’t own a car and never once shopped at our nearby “Lunns for Buns” cake shop, not even for a scone … let alone a couple of my father Fred’s famous meat pies.

They kept to themselves.

After we finally got invited over the fence and into that dark timber house, Jackie noted: “there are no books in the house, no bats, no balls, and no magazines – not even the Women’s Weekly. Neil hasn’t even got a bike! How does he get around?”

I said: “They didn’t even offer us a glass of cordial, let alone a soft drink.”

Jackie said they probably couldn’t afford it.

The first time I saw Neil’s father, Mr Gentle, he was under Mr Reeve’s house which was up on high black stumps, Queensland-style … like all the houses in Annerley.

A tall, old, thin, taciturn man with a few wispy strands of grey hair, he was at the oily ancient timber work bench. He had a carpenter’s saw held in the vice, and he was sharpening it with a file.

Mr Gentle looked like someone’s great-grandfather.

It was extremely rare to see either of Neil’s parents, even when we were upstairs in the house – or Mr Reeve for that matter.

The three old adults seemed to spend all their time in their bedrooms.

When I finally did meet Mrs Gentle, she turned out to be completely grey-haired: that’s when I found out that Neil had been a surprise baby – 17 years younger than his older brother Harry!

In fact, Mrs Gentle thought she was going into menopause until the doctor advised she was pregnant with Neil.

I never, ever did my homework so I was surprised that whenever I popped over to see Neil after school, he’d be sitting alone in an apparently empty house at the dining room table studying school books and doing homework.

Leaning his jaw on his right fist.

He had great powers of concentration (something I lacked) and sat under the one central light which – through his lit-up glasses – magnified his large brown eyes until they completely and hypnotically occupied me.

One eye seemed to be turned.

Slowly we got to befriend Neil. It was a big help that Jackie was a left-hander like Neil, because Neil said he really liked left-handers. (I preferred people who liked left-footers: as Catholics were called back then.)

Eventually, Neil joined us in backyard cricket on our side of the fence.

After our cricket ball accidentally knocked a hole in Mr Reeve’s unused fibro garage, Neil helped us build cricket nets using chicken wire. Then we made a proper pitch by digging fresh dirt from under our house and compacting it.

Once it was finished, we set up fake cricket photos of us catching balls that were actually suspended from the clothes line with cotton – and being clean-bowled by a ball we’d earlier stuck between the wickets.

Everyone wondered how we captured such action photos with our old Box Brownie.

When we finished, we climbed up on Mr Reeve’s garage roof and sat there eating millions of mulberries and talking for hours.

On other days we ate mangoes while sitting on our haunches in our mango tree next to the cubby house; or orange-coloured fruit from the persimmon tree; and, best of all, the delicious large green elongated fruit from our monstera deliciosa patch.

In dints in the concrete under the house we smashed Queensland nuts from our tree to eat the kernels ... but you had to hit them with the hammer just hard enough so as not to crush the nut. (They are now called macadamia, but all the trees were originally from Queensland.)

We soon wore a track to the fence and – sick of climbing over and getting splinters – we cut a hole in it.

Neil used his father’s saw to slice through the foot-thick old rails … which upset Mr Reeve, though he never went down in his yard anyway.

Occasionally, on weekends, we crossed Ekibin Creek and walked a couple of miles to Logan Road to count how many Zephyrs and Holdens we saw pass … or to watch the Redex Reliability cars racing through.

As we did these boyish things with Neil we got to know him.

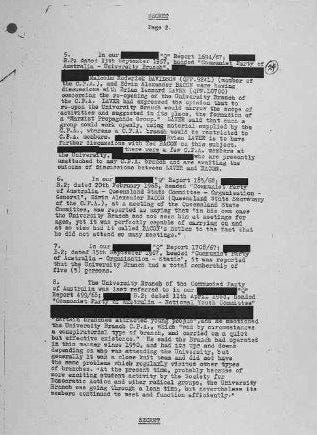

But – at exactly the same time – ASIO (the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation) was also getting to know Neil. Their first entry on Neil was dated March 12, 1954 … soon after he arrived next door aged 16.

It recorded, at the start of Volume 1 of 3 of their file, that “Neil Fraser Gentle” – as ASIO liked to call him – was “in attendance at a Eureka Youth League camp”.

In 1954 the Cold War with Russia was at its height and the United States and Australia were frightened out of their skins by an idea called Communism.

That year America outlawed the Communist Party, and criminalized “membership or support”.

The whole of the USA was caught up in McCarthyism which saw even “suspected Communists” blacklisted so they couldn’t work. In Hollywood, they even blacklisted famous people like Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Arthur Miller … and, of all people, Gypsy Rose Lee!

Australia too had briefly banned the Communist Party at the start of World War II, but the High Court forced a referendum in 1951 at which Australia voted against banning Communists.

I remember that referendum well.

Every day on my way to school aged 10 I saw – painted in huge letters everywhere, even on the footpaths – a YES or a NO.

It was a close-run thing: 49.44% voted YES to ban the Communists, but 50.56% said NO.

Which showed that half the country wanted Communists and all their supporters jailed.

Still, I’d never heard of the Eureka Youth League – and Neil never mentioned it – but the ASIO files said this was the youth arm of the Communist Party of Australia.

And my mate Neil was in their camp.

Still, Neil never said anything against Catholics or Australia. He just wasn’t the type.

Like us, he listened to the serials on the wireless at night (there was no TV until 1959); our favourite was Journey Into Space ... “the story of a voyage to the Red Planet Mars”.

So the three of us sat in Mr Reeve’s dining room and listened together for one exciting night each week.

On Friday nights we gathered around the wireless again after shifting the white needle to the boxing from Brisbane Stadium: Mickey Hill versus Stumpy Buttwell, “a left-rip to the body, a right to the head, an uppercut to the chin…”

We could see it all happening in our minds.

Neil was by far the smartest person I’d met: he could show us Mars in the sky. He was even smarter than Jackie who was near top of his class.

But Neil wasn’t anywhere near as tough.

Jackie was a boxer and rabbit-killer exponent who wore a bone-handled knife on his hip and carried an air rifle … Neil did none of those things. Though what none of the State School Kids knew was that Jackie had to wear glasses at home to read.

Back in the 1950s every Queensland kid was judged by how well they did in the statewide State Scholarship Public Examination aged 14.

This exam decided which pupils were smart enough to receive a scholarship from the state to pursue a secondary education.

If you passed, your name appeared in the list in The Courier-Mail. If you didn’t, your name was notable by its absence.

Because the Queensland government hadn’t built any new State Secondary schools for 25 years, the exam had become harder and harder … until the fail rate achieved was 40%.

I passed by one mark out of 400.

Top-of-the-class people got 80% in State Scholarship, but almost no one got 90% over the four exams – Maths, English, History, and Geography.

But Neil did.

In my book this made him a genius … and he could help me understand lots of things I didn’t know.

Neil was studying Chemistry at State High and made our lives even more exciting: he showed Jackie and me how to boil lead on the gas ring next to the vice under Mr Reeve’s timber floorboards, and then pour the molten lead into a saucepan full of water.

There it assumed strange shapes as it hardened.

Sometimes, Neil would put Guy Fawkes red penny bungers in cans and blow them into the sky – so high that we’d try to catch them when they finally came back down to earth.

A mixture of potassium chlorate and sulphur (from memory) on the tram line would cause a loud bang as the tram passed over – which made everyone in Annerley Junction stop and look.

Neil could also make things.

Before he arrived in Annerley, he had made canoes out of flattened corrugated roofing iron to put into the Brisbane River at Highgate Hill … where he and his mate, Crom, had rowed them into the wake of the ferry heading for the Koala Sanctuary at Lone Pine for a wild ride.

Neil helped us build a second canoe – sleeker and faster than our original. But Jackie and I took our canoes down the road to the safety of Ekibin Creek, which was about four yards wide.

One time, Neil made us a pirate cutlass out of aluminium – curved pirate handle and all – drilling holes through the cutlass while it was held in Mr Reeve’s vice.

Then one day, when Jackie and I found an old steel skeleton of a bike at the dump and carried it home, Neil said we could make a bike for ourselves. It already had rusting handle bars so he said all we needed were pedals, a chain, and two wheels.

After we put the bike together, Neil painted it like new – even down to a multi-coloured chevron on the front using tiny paint brushes.

Now that we each had a bike, we decided the three of us would go on a great adventure: we’d cycle down the Pacific Highway to the South Coast 50 miles away for a swim and camp overnight.

Jackie and I rode our bikes all over Brisbane so we weren’t expecting any opposition.

But the small figure of Mrs Gentle (not for the last time) stormed through our hole in the fence (even though she’d objected when we made it) protesting.

She said we couldn’t go: it was too dangerous, too far, and we were too young.

Hearing the commotion, my mother Olive arrived down the back stairs and the two mothers colluded to stop us.

But Neil was allowed to join us for the summer school holidays in our tents on the 10 acres of swamp Olive had bought at Labrador in the bush on the South Coast (now called the Gold Coast).

So we rode into Roma Street Station and put our three bikes in the Guard’s carriage at the back of the train to Southport, and from there rode several miles north to our 10 acres … where Fred and Olive were pitching the tents.

We boys needed our own transport to reach the Broadwater and Loders Creek for a swim each day.

The first time we walked into the swamp with Neil, a snake came at us, and as we cleared off, I threw my bone-handled knife at it and was proud that I only just missed.

But I never went back to get my knife

After that, I put a length of rope around our tent because on the back of The Phantom comic it said this stopped snakes.

As well as my two younger sisters Gay and Sheryl, Fred and Olive brought our Irish-American boarder, Mr Jimmy Stewart, for the holiday.

Mr Stewart had been complaining about never seeing a snake: so we told him there was “a snake under every log in Australia”—and he was stupid enough to believe us.

There was a huge log on the ground near our tent, and I asked Neil to lift up one end so Mr Stewart could see the snake.

Neil was laughing as he struggled to lift the end up above his head ... and Jackie and I were struck dumb when an angry brown snake crawled up the side of the log towards Neil, with Mr Stewart saying, “Well, that’s a fine specimen.”

We shouted to Neil about the snake, but he kept laughing and said over the side of the thick log: “How many heads has this one got, Jack?”

Kids who passed the “Junior” public exam at the end of Grade 10 went on to do the “Senior University” exam at the end of Grade 12.

But, although Neil got all A passes, he surprised his teachers by leaving school to become a technician-in-training with the government-owned PMG … which provided all telephones and communications and delivered all letters.

PMG stood for Post Master General, but Olive called them the Public Money Grabbers.

Neil never told his parents he had applied for the job. He knew that – even with his scholarship – they didn’t have enough money to keep him at school any longer.

ASIO didn’t miss this latest news on 16-year-old Neil either.

His file says: 7 Dec 1954 Employed in PMG and included in an index of communists in the Commonwealth Public Service.

ASIO had already noted that Neil’s brother Harry “has associated with known communists in the Darwin area for several years and is a suspected communist sympathizer”.

Yet Harry had served six years in the Australian army in World War II.

I met Harry at the dining room table when he came to visit his family after many years away. I liked him immediately because he sat back in his chair and chatted easily to Neil, Jackie, and me.

We were impressed because Harry arrived in a rare, huge Austin A50 … driving thousands of miles from Darwin.

He looked a fair bit like Neil, but a softer, less hardy, more out-going version. In fact, his inoffensive manner reminded me of a Church of England Minister.

I wasn’t the only one.

“Near Mt Isa,” Harry related, “a copper pulls me over for speeding. But when I get out of the car he apologises! He says: ‘I’m so sorry Reverend, I didn’t realise you were a Minister of Religion’.

“And I said: ‘How did you know, Officer?’

“And the copper pointed to the badge on the side of my car – Austin of England – and he said: ‘I saw the sign on your car: “Church of England’”.

We all had a great laugh.

At the start of 1955, I arrived at St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace, where joining the Army cadets was compulsory. So, aged 13, I was issued with a uniform, boots, and the famous brown slouch hat. (The .303 rifle came months later.)

That weekend I tried them on and practised marching around the back yard … when Mrs Gentle appeared through the hole in the fence for the second time.

She was shouting … this time about me killing people and fighting wars and that I should be ashamed of myself parading around like that.

I didn’t understand her outburst.

But then I didn’t know what Mrs Gentle had been through: the isolation she must have suffered.

According to ASIO, Neil’s whole family was in the Communist Party – his mother, his father, his two older sisters Pam and Janet, and Harry.

ASIO wrote about Neil: “It can be assumed that the political influence in the family is strong as his brother and two sisters are adversely recorded … His mother and brother have been active in Communist Party of Australia fronts”.

ASIO must have been listening in on the family because it reported: “Robert Delisle Gentle [Neil’s father] stated that every member of his family was a member of the Communist Party.”

Neil was inadvertently involved in the Communist Party very early.

At the start of World War II when the Menzies government outlawed the Communist Party, Mrs Gentle would put Neil in his pram, tuck Communist Party literature under his mattress, and take him out to distribute these illegal pamphlets

Mrs Eileen (known as Gert) Gentle had a fierce character.

She was the daughter of a wealthy doctor, but her whole family cut her off when she joined the Communist Party. One family member told me: “Gert refused to buckle under and said goodbye to an enormous amount of money.”

As a married woman with children living in Highgate Hill, Brisbane, she was known to throw the cutlery out the window when she was angry. “The gully below their home in Dornoch Terrace was littered with the spoons and forks of many arguments,” a family member told me recently.

Another time I met Neil’s sister Janet at the empty dining room table next door (in mid-1955) … but the person who attracted my attention was her husband, Jim Henderson.

Mr Henderson was well-dressed in a suit: a jovial, articulate man with a big actor’s face and black hair brushed directly back.

He spoke of things I’d never heard anywhere else.

Neil and I were listening to the rugby league Test between Australia and France from the Gabba. Australia was the world champions and had beaten France easily in the First Test and, with 10 minutes to go, was 13 points in front.

We thought the match was over, but Jim Henderson said authoritatively in his deep voice: “No. Australia will lose now because they have to attract a big crowd at the SCG next week.”

I thought he was crazy – but we did lose.

Little did I know, aged 14, that jovial Jim Henderson was a leading Communist Party figure.

Eleven years earlier (after the Communist ban was lifted awaiting the referendum result) he was campaign manager for Fred Paterson who became the first and only elected Communist Party politician ever in Australia.

This led to Mr Henderson being appointed to a fulltime job with the Communist Party in Brisbane.

The ASIO files told me that five years later, in 1960, Jim Henderson moved to Hanoi for a couple of years with Neil’s sister Janet where, a former school teacher, he worked as Ho Chi Minh’s English translator.

(This was a few years before Australia committed troops to the Vietnam War.)

Medals Jim Hendersen received from Ho Chi Minh were found in his papers when he died in 1998 … together with his unpublished autobiography: “Memoirs of a Communist”.

He also left behind a pamphlet “Security and Peace v. Profits and War”. Political material must by law always say who it is printed by, and his pamphlet says: printed by R.E.Volt.

Mr Henderson loved to play around with words.

Though no longer a schoolboy, Neil brought home interesting stories on becoming a telephone technician.

The technicians-in-training were lectured by older Techs and Neil told us one of them warned the young trainees always to wear a jock strap to support their wedding gear while playing sport … because he hadn’t and now suffered terribly.

I went out and bought my first jock strap the next day.

Within a couple of years, Neil bought a tiny old Morris Minor car and – since Jackie and I had recently bought a second-hand .22 rifle – we decided to drive down over the border to Woodenbong in New South Wales to shoot rabbits.

I was tremendously excited at the prospect as we drove all night to be there at dawn when, Jackie said, the rabbits come out.

But by the time we got there I was too tired to get out of the car with them and stayed inside and slept.

Once, Neil took Jackie and me inside the South Brisbane Telephone Exchange to see the walls and walls of whirling machines reaching the ceiling which automatically connected up thousands of phone calls.

Neil carried a phone with him which he could plug in and hear the conversations – to see if everything was working properly. (Back then you got “crossed lines” on the phone all the time – as frequently as you now get scam calls.)

Neil was in good with the PMG because – though only in training – he had already invented a new part to make those machines work better.

When I got a girlfriend in 1958, she was on the Gold Coast for Christmas and I wanted to see her. So Neil, who didn’t have a girlfriend, drove me down to Nobbys Beach in his Morris Minor and took us to the drive-in theatre.

While I sat in the back cuddling her, Neil watched the picture from the front seat and never once turned around or complained.

The next year, 1959, Neil saved me from getting the cuts with a thick leather strap in my final year at school.

On Friday afternoon our Maths teacher “Freddie” set us a sum to do on the weekend. He said: “This was on last year’s Senior Maths paper and no one in the whole state got it out! On Monday I will be calling someone out to do the sum on the blackboard in front of the class.”

Somehow, I knew I would be the “someone” Freddie picked – so it was straight through the hole in the fence to Neil, even though he hadn’t yet studied Senior Maths.

It took him about 10 minutes to do the sum and then he explained all the steps on the way to the answer: on Monday morning I hit the blackboard like a Professor of Mathematics and Freddie couldn’t believe it. I was saved for another day.

A real friend I’d say.

But, even so, though I’d known him for six years, Neil still had never mentioned the Communist Party or the Eureka Youth League. Looking back, I can understand why: it was bad enough being a Catholic in the 1950s, without being a Commo.

I guess Neil had always felt like the facer card in the pack – facing the other way from the rest of society: being born into a family where he had to keep this secret from everyone else.

1960 was a sad year because Neil moved away from next door: to Gayndah to look after telephone lines in the bush. This made life difficult for him because he had been studying six subjects at night to do Senior – now he had to start again and do them all by correspondence.

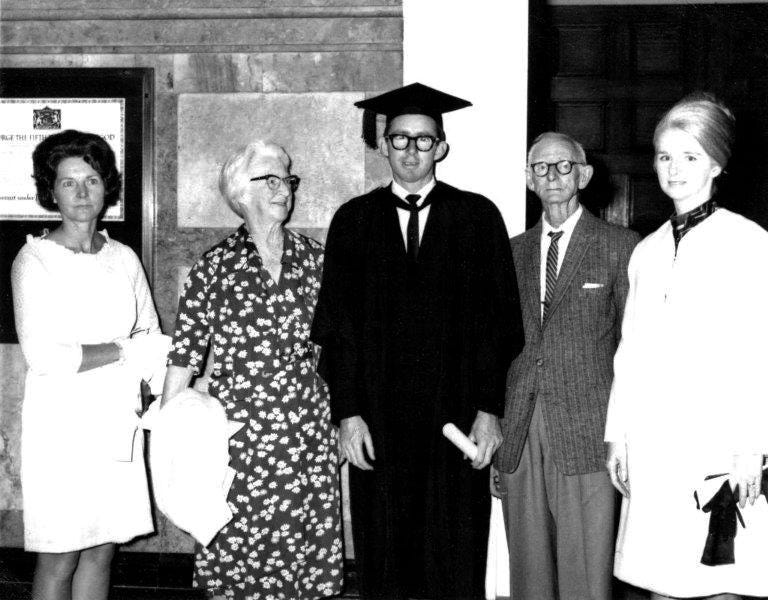

Despite this, Neil passed Senior and, in 1963, won a PMG scholarship to study electrical engineering fulltime for four years at the University of Queensland (UQ).

Meanwhile, Jack and I had become reporters and we didn’t see Neil for many years.

In June 1964 ASIO reported: Neil Fraser Gentle, as vice-president of the Eureka Youth League, opened the State Conference at the Brisbane Trades Hall and the evening was given over to singing, reading of poetry, and dancing.

ASIO’s inside source reported: Cakes and tea were provided by the League for all present.

Neil’s first wife, Gerry, told me last week: “The Eureka Youth League was like Young Labor or the Young Liberals for the Communist Party. At their camps they sang folk songs, put on Australian Plays, and other revolutionary activities! So Neil was Public Enemy Number One.”

Two months later ASIO reported: Neil Fraser Gentle criticised a Truth newspaper article for ‘attempting to infer all folk singing groups were run by communists’ … Three members of the University Branch [attended], including one young, well-built male with a black beard (case officer’s comment – possibly Max Ernest Robinson).

“That would have been me!” Max Robinson told me from Victoria last week.

Max studied electrical engineering with Neil and they were both members of the UQ Communist Party branch.

ASIO even reported on Max’s engagement party at Seven Hills, so I asked if it was clear to him they had been infiltrated by ASIO?

Max said that at a reunion lunch recently one bloke openly admitted he had been paid by ASIO to report back, even when he was at High School.

Did Max get angry?

“No,” said Max, “I said ‘I don’t want to hear about it’ and walked away.”

Reading the files today it is clear ASIO had someone inside their group for years.

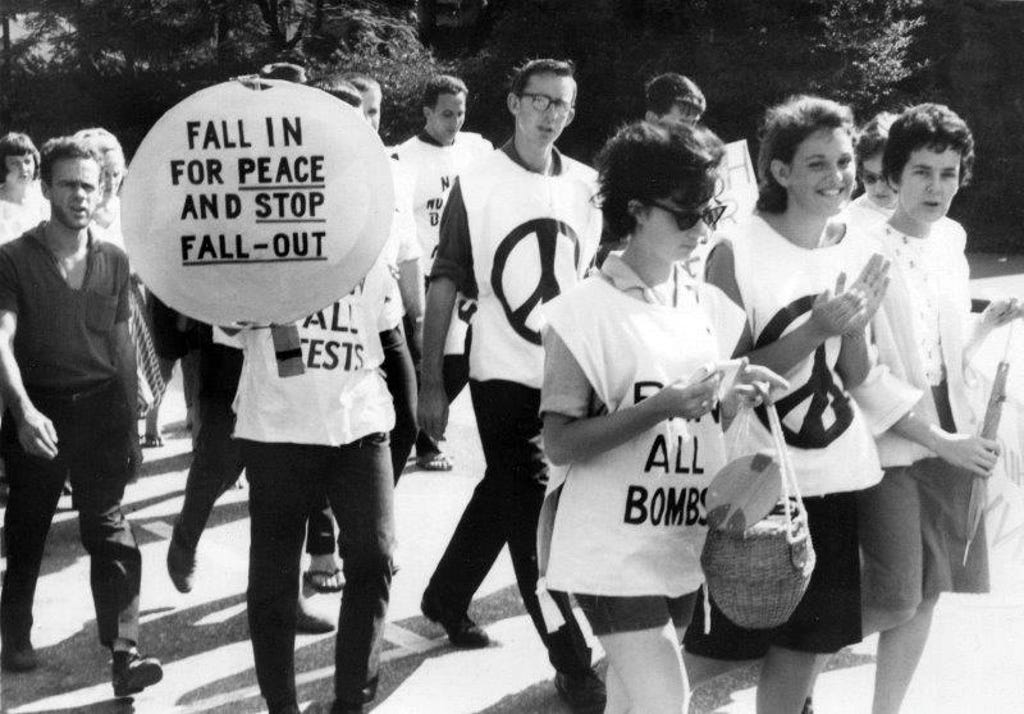

On November 30 1964 ASIO predicted that members of the Eureka Youth League would demonstrate against Prime Minister Menzies during his address at Brisbane’s Festival Hall.

The following persons [including Neil and Max] were observed to enter Festival Hall and sit therein as a group. Nearing the conclusion of the PM’s speech some of these persons stood up and held aloft printed placards that read “NO CONSCRIPTION”.

(The next year, conscription was introduced for the Vietnam War.)

By 1965 I was 23 and living in Hong Kong as a reporter seeking to get into secretive Red China, a country Australia refused to recognise.

ASIO (presumably) ignored me, but reported on a social evening in Brisbane at that time: “About 70 persons attended including Neil Fraser Gentle. The function consisted of playing records and drinking beer … in all 18 dozen bottles of beer were sold”.

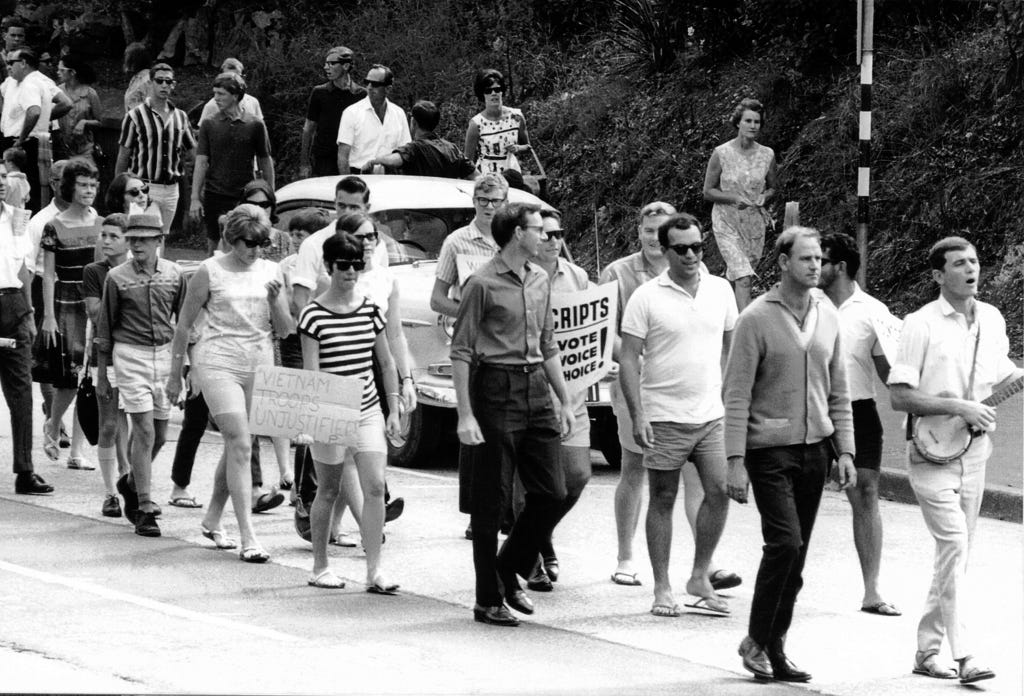

In May – while I was in Red China reading on a Wall Newspaper that we were sending troops to Vietnam – Neil was observed taking part in a demonstration against American and proposed Australian action in Vietnam.

By June 1965 I was working for the London Daily Mirror and my mate Neil, now 27, was listed as elected to the new State Executive of eight persons of the Communist Party.

He was “observed” at a Youth Against Conscription rally; at a Eureka League film night; and in an Ipswich-to-Brisbane relay walk for nuclear disarmament.

ASIO was also photographing Neil surreptitiously:

29 Nov 1965: Observations were carried out in conjunction with a Photographic Operation [blanked out] in connection with a State Council meeting of the Eureka League in Fortitude Valley.

The following persons of security interest were observed to enter the premises:

1.06 pm Neil Fraser Gentle

During New Year 1966 ASIO was at a Eureka League camp and breathlessly reported it was “unorganised and lacking in political indoctrination”.

When names weren’t known, ASIO attempted to describe suspected Communists attending a party:

j: u/i [unidentified] male aged 20 years 5’10”, solid build, short black hair, piggy eyes

k: u/i ex Melbourne Uni 5’7” slim build, long blonde hair, seems effeminate, 23 years

l: u/i male aged 34-35 sandy hair 5’8”. Has very large paunch

m: u/i male 15 years thin blonde Beatle hair. Wore a T-shirt with “Some People” across the back. Takes part in rallies. Has an uncle who had one leg removed and who is a well-known saxophone player.

You couldn’t make it up.

Three months later ASIO’s secret agent reported on the Eureka League camp at Caloundra: badly organized, there was a noticeable lack of activity … discipline at the camp left much to be desired: it was mentioned that leading members, both male and female, went on nude night swimming excursions.

In 1967 Neil was awarded his UQ engineering degree with First Class Honours.

Max Robinson said Neil had made the mistake of promising to buy a keg of beer for every High Distinction he achieved.

A party was organized at the house Neil shared with Max and other students nick-named Hormone House – though Max said this was “more in the intention than the success”.

“Even engineering students couldn’t drink all the beer Neil had to buy … so there was enough left over for a friend’s wedding.”

In April the Eureka Youth League Valley Branch and the Communist Party Northside Branch put on a film night … ASIO’s Agent reported there were only 20 people; the projectionist was Neil Fraser Gentle; they watched three films including a Cinesound film about a day at the beach.

A raffle was conducted at 20c a ticket. Three prizes, each one a bottle of beer. Only 20 tickets were sold. Beer was sold at 13c a glass. Cordial was also sold at 5c a glass.

In 1967 I was in Vietnam covering the War for Reuters, London, when ASIO excitedly reported that 29-year-old Neil had a girlfriend!

Their Agent typed out that Neil’s current girlfriend, Miss Brittain, appears to be in her early 20s. Her father is on the university staff and she previously lived in Hawaii. She speaks with an American accent.

This was Gerry Britten whom Neil met at UQ preparations for an anti-Vietnam War demo; they married the following year.

Meanwhile ASIO was producing a Folio discussing the possible security risk of Neil Fraser Gentle which concluded: There is no doubt Neil Fraser Gentle constitutes a security risk.

So ASIO recommended the PMG be directed to his political background and a request made to arrange his employment future into areas of work where little or no risk is involved.

Thus, the Public Service Board wrote to the Director-General of ASIO saying the department had decided to have Neil moved to a “safe” area.

“The work is very routine and lacks challenge for a good engineer and the Dept is hoping that dissatisfaction with duties may, combined with possible post-graduate work, cause Mr Gentle to be attracted to employment outside the service.”

In this hidden-from-view clandestine background, at the highest level of our government, Neil’s livelihood was being manipulated and his PMG career stymied.

Even though membership of the Communist Party hadn’t been banned.

As Gerry Gentle told me last week: “When you have the whole machinery of government out to get you, life becomes difficult.”

Despite all this, Neil’s academic brilliance still shined through.

In 1968 he was awarded a Master of Engineering Science from UQ. Neil then wrote a paper titled “Alternate Routed Networks” which caused PMG Head Office Research Labs in Melbourne to seek to recruit him.

“So Neil could have had a job there that would have utilised his intelligence and skills for the benefit of the country,” Gerry told me.

“But then one of the engineers went to a phone booth to ring Neil to say ‘there’s been a security strike against you and a bar put on your move. They’re planning to send you to Charleville!’”

In 1971 – though it was now more than 30 years since baby Neil had slept on Communist documents in his pram – ASIO continued to follow him around: even though the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 had seen the Communist Party fall apart in factions, even within Neil’s family.

Such was the political fracturing in the family, that Neil’s sisters Janet and Pam would meet up without their husbands, Neil’s second wife Noeline told me.

“When I eventually met some of them,” Noeline recalled, “I noticed that all the family was cautious with each other. Quite distant. They seemed to keep themselves separate. There was a strange disconnect.”

Neil himself was gradually moving away from his Communist background, but ASIO that year still described him as “of security interest” when he was seen at a Women’s Liberation Movement and Abortion Law Reform Association rally.

Thus, in 1972 Neil decided to get a job overseas and applied for a UN position in Indonesia ... to get away from it all.

ASIO heard about this, and warned that such Indonesian appointments were made without checking with Canberra.

Gentle’s qualifications are such as to ensure his employment in almost any position in his particular field … Gentle is an expert in telephone traffic engineering. He is the most highly qualified engineer in his field in Queensland.

Neil never got the job.

At that time Neil was, ASIO wrote: a Category “A” risk in the Index of Persons of Security Interest in Commonwealth Employ.

In December 1972 — after 23 years of continuous conservative government — the Australian Labor Party’s Gough Whitlam became Prime Minister.

I would have thought that would be the end of government harassment, but ASIO remained nervous about my friend Neil, recording anxiously that he now also held a Diploma of Computer Science from UQ.

Adding: In his own field he is one of the most highly qualified electrical engineers in Australia. As such, he occupies, and will continue to occupy, a key position in Australia’s communications system.

On 18 January 1973, ASIO listed the husband-and-wife team of Gerry and Neil of security interest to Headquarters.

ASIO was obviously tapping their phone, writing: A recent intercept … some friend has invited them to visit Hong Kong … attempting to identify the person who issued the invitation to the Gentles.

By 1974 Neil and Gerry had decided to leave Queensland and move to Canberra because Gerry, an economist, had obtained a job in Treasury. So Neil applied for a job as an engineer in the federal Department of Transport.

ASIO noted: no access to classified matter was involved in the job for which Gentle had applied.

On March 12 1974 ASIO said it had received information that Neil and Gerry – in expectation of the Transport Department appointment proceeding have disposed of their home in Brisbane and rented one in Canberra.

Gerry Gentle takes up the story:

“The Bureau of Transport Economics was looking for intelligent engineers and of course Neil walked into the job when he applied. We were all set to move – to drive down the next day – when Neil was informed they had rescinded the position!

“It was a kick in the guts.

“My boss was the previous head of the Bureau so he took it up … and Neil’s job was reinstated. But ASIO blighted his career: the sad thing was that Neil was never game to apply for anything anywhere else after that.

“He spent his whole professional life there while others, much less qualified, were promoted over him, though a couple of international jobs sought him out – with the UN in Bangkok for nine months, and reporting on Indonesian transport options in eastern Indonesia.”

After the 1975 Hope Royal Commission into the Australian Intelligence Community (established by Gough Whitlam), ASIO pulled their head in and got rid of the black ban on Neil and closed the file they’d started when he was 16 in 1954.

But, as Gerry said, “Neil never got to fulfill his potential.

“The ASIO files show they were reports by half-wit agents. They said Neil continued to consort with ‘these people’ – these people being his sisters, their husbands, his brother, and his parents!”

Gerry and Neil had two sons, Nick and Ian, but divorced in 1982 after 14 years.

“Neil never talked to his two sons about his early life,” Gerry said. “The whole episode was horrible … and it went on for so long, nearly 40 years.

“For Neil, there was so much pain.”

Noeline, Neil’s second wife, said: “It seems like he was unnecessarily hounded, watched, and harshly judged for earlier political views way past the time when he was politically active: for at least ten years.

“It was just so unjust.”

Noeline (mother of two sons) and Neil (father of two sons) began their “forty wonderful years together” when a group of bush-walkers were car-sharing “and Neil used that famous Aussie pick-up line ‘Come in my car’.”

In the Transport Department, Neil investigated national problems such as fuel efficiency, planning for fuel shortages, Bass Strait freight rates, the economics of using treated sleepers for rail tracks, and waterfront reform.

In retirement, Noeline and Neil went bushwalking, taught English in Chile, volunteered as “practice patients” for first year medical students, and took in foreign students. Neil became a serious runner and a volunteer counsellor with Lifeline.

Neil Gentle died last month. He was 86.

His two wives and two sons were at his bedside and his last words to his sons were: “Don’t hold grudges, it’s a waste of energy.”

EPILOGUE

At his funeral Gerry told mourners; “Neil had a lot of love and loyalty: he looked after, and took care of, his older brother Harry himself. He was born into a Communist family, so grew up with values relating to equality.”

Noeline related. “Neil was so smart that my brother-in-law nicknamed him ‘Gandalf’ after the wizard in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.”

His son Nick said he and his brother Ian were ignorant about Neil’s early life.

“It was only revealed to us when we were adults. At Uni I didn’t know what job I’d do and one night I said: ‘Maybe I’ll join ASIO’, and the reaction was NO! No! No! That’s when it was told to us.

“It just didn’t jell: the stories of dad’s youth and the bloke who brought us up.

“We had Neil 2.0.”

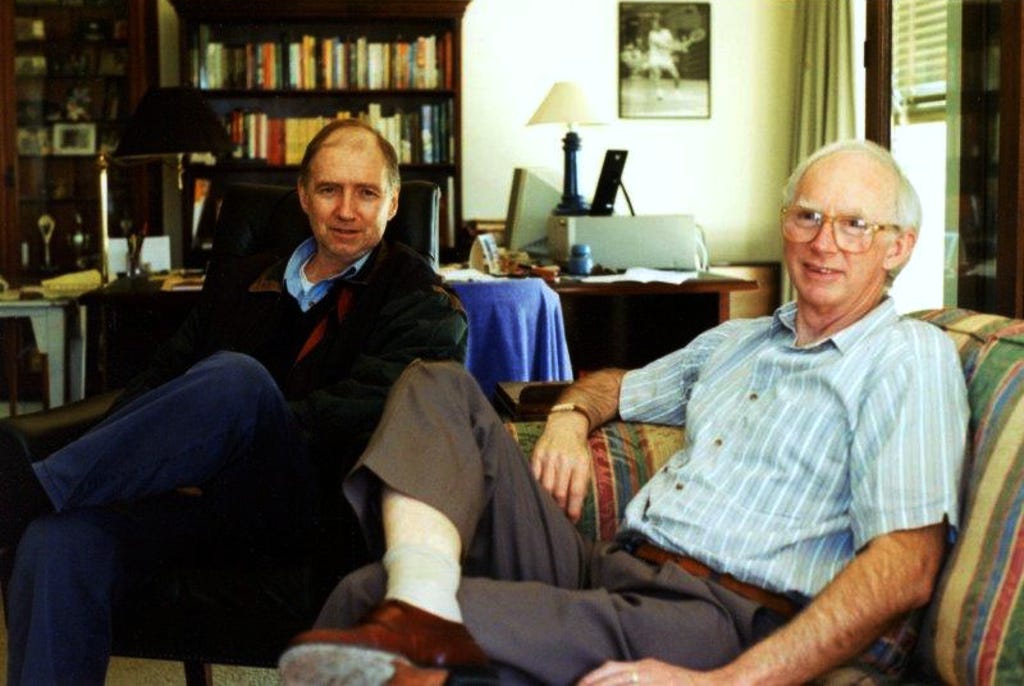

PS: Neil and I got together several times over the decades – including after he figured in my childhood memoir Over the Top with Jim in 1989.

I was apprehensive when he turned up because you never can tell how people will react to what you write … and I had said his family were Communists. But it was as if we were boys again eating mulberries on Mr Reeve’s garage roof and talking for hours.

One reader of this substack story of mine said he had had a lot to do with ASIO and commented "everyone there calls it 'as 10' or 'the firm'. He seemed to know an awful lot about it ... and included people's middle names!

Both of Neil's wives emailed to say how much they liked the story -- Gerry said as she read it "I am close to tears as well as laughter"; Noeline said: "What got to me was the fact that they made all those assertions which were so damaging without actually checking their validity with Neil himself".

Gay just added to her note below (on email) on my reply:

"I REALLY LIKED NEIL AS HE WAS SUCH A KIND, CARING, UNASSUMING, GOOD BOY, who was destined to become THE MAN HE WAS.

With such adversity in his life, I am so happy he had a nice life with 2 wives and 2 sons and 2 Degrees!

I add this because I didn't have room in the story to say Neil later got an Economics degree from ANU!!!! A diverse talented man.