It was July 1969. Two men landed on the Moon while four men sat with me at the end of the Earth caressing their thousand-year-old stone axes.

These axes – each made from a sharpened smoothed black stone bound by vine into a hollowed forked polished tree branch – were their tools of trade.

I tried to buy one, but money was useless here and I was rebuffed. Eventually, I swapped my wristwatch for two of these stone axes and have never worn a watch since … something which never fails to cause comment.

But I still carry those two stone axes with me every time I move house.

We were at the bow of a ship ploughing along the Equator in a flat sea, with the Moon in half-bloom overhead – the movement through the tropical night air cooling us down.

Through the static of my portable radio, I enthusiastically explained to the four Papuan men that a spaceship had just landed on the Moon above us, and an American astronaut was climbing down a ladder.

He had stepped foot on the Moon!

Our ship was headed from Manokwari to Fak Fak around the "bird's head" in the top left-hand corner of West Papua – the western half of the island of New Guinea. As we hunched around the radio the four Papuans fell silent: no enthusiasm at all as they stared at the white needle on the radio's dial.

Perhaps, it occurred to me, they didn't believe it. And why should they? These men had never been on an aeroplane; never seen television; never spoken on a telephone.

Just then the Papuan chieftain, Ibrahim Bauw, looked up at the Moon with a big smile and said it was good that the Americans had gone there.

Why? I asked.

"Now one day we will be able to go to the Moon too,” Bauw said, adding, “I hope the Americans will become like the Moon and light the Earth."

Meanwhile, the youngest man fingered the cool sharp stone of his axe and wondered if rocks on the Moon would be different from the rocks in Papua. "I would like one of the rocks from that Moon for an axe," he said.

There was great irony in this historic moment.

The whole world was looking upwards for five days, enthralled by this "one giant leap for mankind" … while, at the very same time, the whole world was ignoring the backward step mankind was taking down here on Earth.

At this very moment in West Papua, 800,000 reluctant Papuans of the former Dutch New Guinea were being subsumed into Indonesia. This rich verdant land the size of France – with permanently ice-capped mountains on the Equator – had become something others wanted.

When the Dutch lost their colony to the new Republic of Indonesia, they vowed to hold on to just one part – Dutch New Guinea. They argued that the Papuans were Melanesian and not part of the Indonesian archipelago and, because they were living a Stone Age life, needed looking after… and, just by the way, Dutch geologists had reported home that on one mountain alone deep in West Papua there was so much gold ore they could smell it. (This is now the richest gold mine in the world.)

The Dutch sent an aircraft carrier. Indonesia sent gunboats. They clashed.

America intervened to stop war; to stop Indonesia turning Communist; and, some allege, to stop the mountain of gold going to anyone else.

In 1962 the Indonesians and the Dutch (but not the Papuans) were invited to New York where an "Agreement" was drawn up with American help. The Papuans would be given seven years to prepare to decide their future.

In the meantime, Indonesia would administer the country before holding an "Act of Free Choice” – overseen by the United Nations.

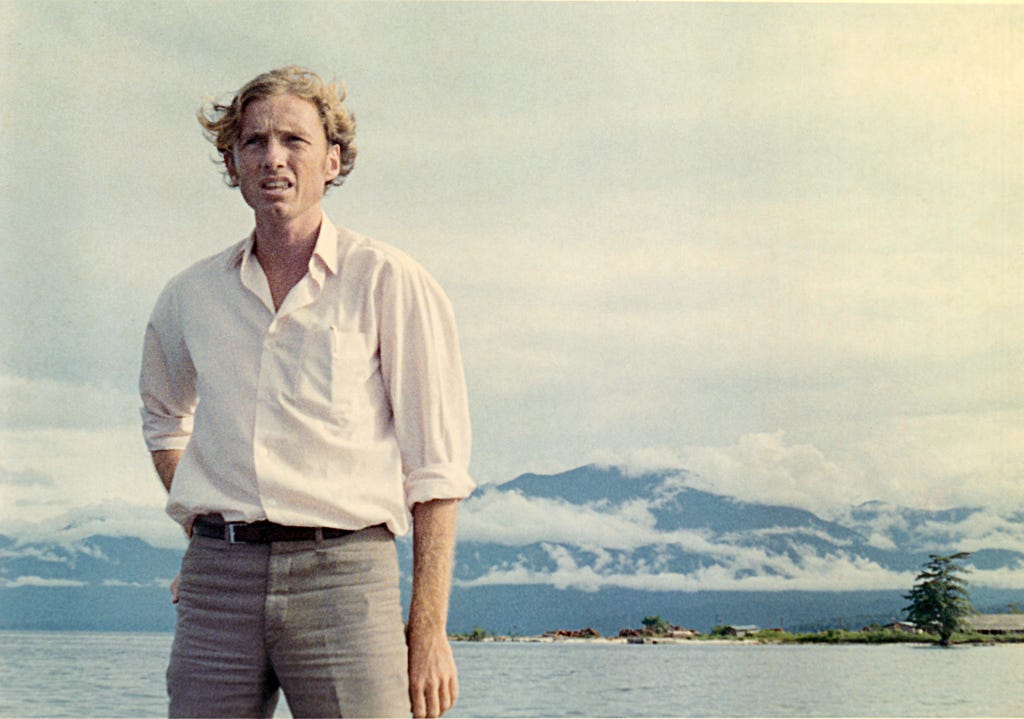

This was why I was on that ship in July 1969; I was covering that “Act of Free Choice” for Reuters of 85 Fleet Street, London.

With almost no roads, the only way to get around was by air or ship. It tells you something of the lack of interest down here on Earth that only two reporters – myself and Otto Kuyk (the foreign editor of Amsterdam's De Telegraaf) – covered the whole thing.

Foreign correspondents from all over south-east Asia, representing the world's most famous newspapers, magazines and TV stations had come to this isolated part of the world – 2,000 miles east of Djakarta – two months earlier to preview the “Act of Free Choice”. But none of them returned to cover the actual event because, at exactly the same time, the President of the United States of America, Richard Nixon, had decided to tour Asia … including a two-day visit to the Indonesian capital.

Smack in the middle of the “Act of Free Choice”.

The arrival of an American President in Asia was the biggest possible news story. All correspondents – including myself – were instructed to stay at their desk and prepare. This was in the era when even Reuters, the world leader in communications, sent their stories from Djakarta by Morse Code at 20 words a minute.

With an American President, any incident, any speech, any slip-up, any new policy, would be the biggest story in the world that day and dramatically move stock markets around the globe.

I ignored the instruction and flew to West Papua because I thought it was a big story.

Suffice to say, while the world was looking the other way -- at Nixon and the Moon -- the Papuans did not get a Free Choice.

There was no secret ballot for all adults (a plebiscite) as one might expect.

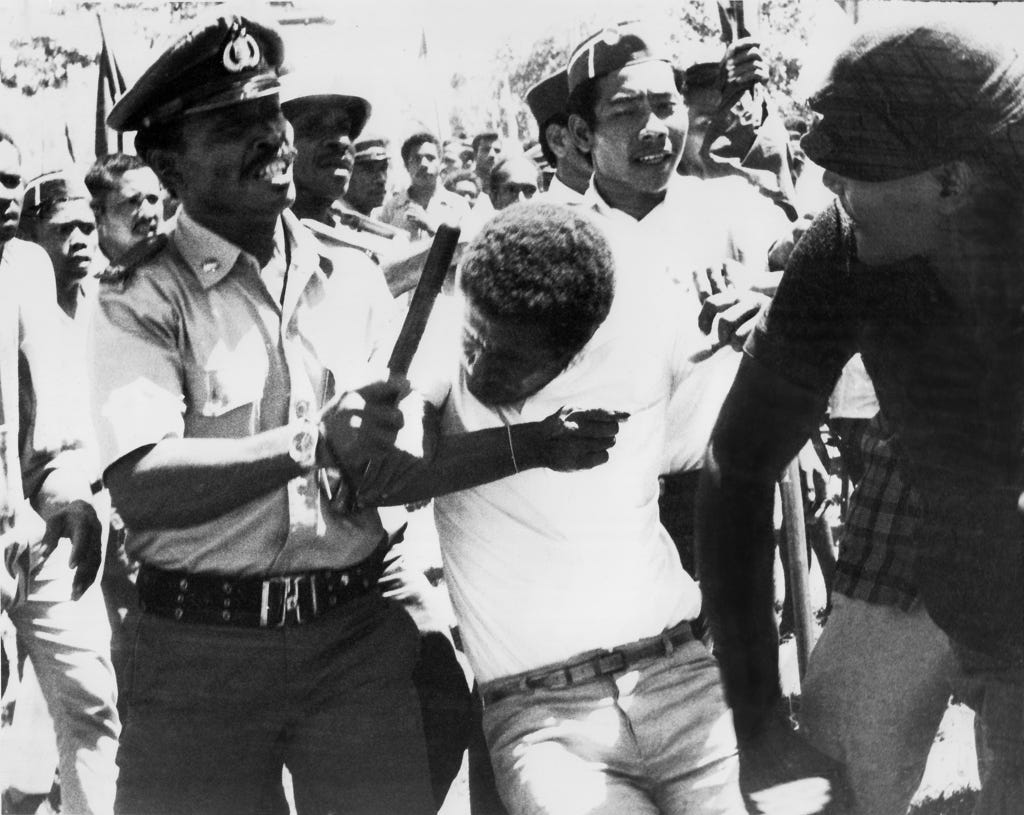

Instead, in each of the eight province capitals an average of just 130 mainly men were selected (rather than elected). They were given new clothes and gifts such as radios, underpants, torches, and briefcases and herded into halls with Indonesian troops in civilian clothes everywhere around.

After a few were allowed to speak – along with Indonesian officials – these chosen delegates were asked to stand up if they chose to be part of Indonesia.

Of course every last one of them had to stand up – or else be seen to be supporters of the banned Free Papua Movement (OPM). And they did. But the looks on their faces, the contacts made at midnight, the letters soaked in blood, the arrest of protesters carrying a hand painted sign “ONE ONE VOTE” (sic) showed Otto and me it wasn't remotely a free choice.

In Manokwari – when it finally dawned on locals that the UN was not going to protect them and that they were going to become Indonesians – Papuans outside the meeting started yelling out "sendiri" "sendiri" – alone, alone.

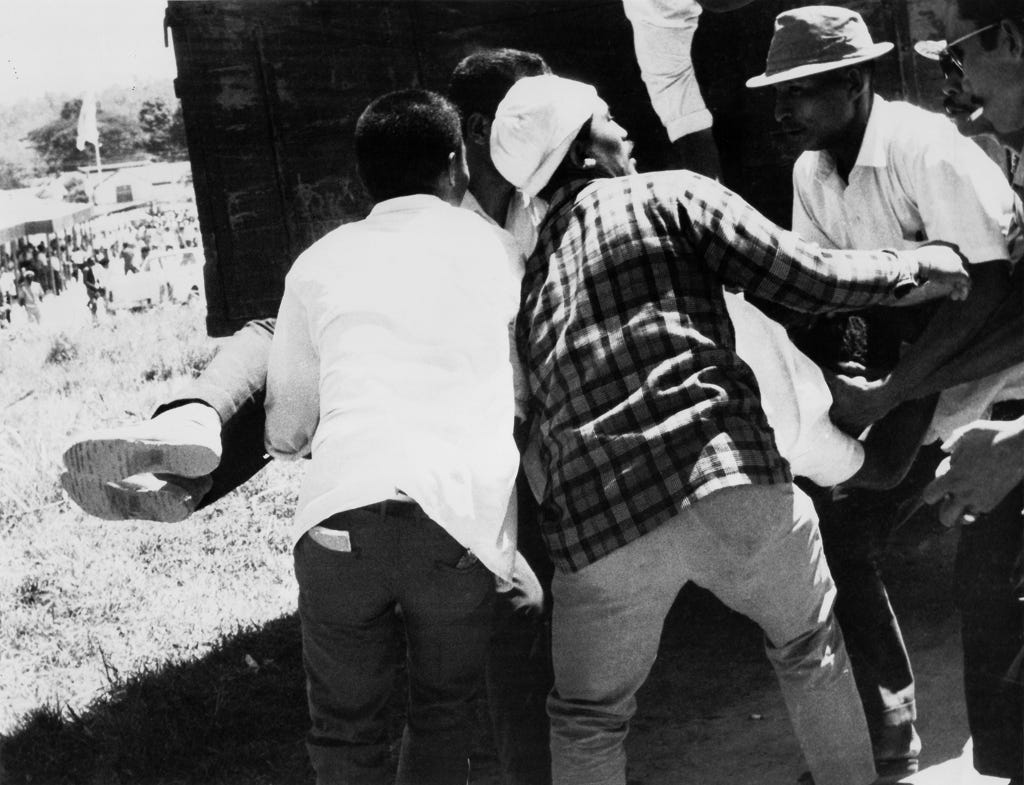

Indonesian soldiers dressed as civilians quickly lifted up a dozen (that I saw) of these men and threw them head first into the back of trucks without bothering to lower the tail-gates first. I took a photo of one protestor being hit over the head by an Indonesian policeman's baton at the same time as a soldier powerfully punched his jaw.

A policeman showed his revolver so I ran down the hill and back inside the hall to where the future was being decided.

I rushed up to the head of the UN delegation, Dr Ortiz Sans, of Bolivia, who was observing proceedings and, in a bit of a panic, told him Papuans who called for independence outside the hall were being bashed up and taken away in military trucks.

Dr Sans looked up at me disdainfully and said: "My job is to observe what happens in here."

He had always pointed out that the special wording of the New York Agreement meant the UN, although lending its name, could only “advise, assist and participate”.

Later, back on the ship in Manokwari harbour, Dr Sans sidled over to me for the first and last time to carefully explain his difficult position to this 28-year-old Australian: not for publication, of course.

"West Irian (West Papua) is like a cancerous growth on the side of the UN," he said, "and my job is to surgically remove it."

Today, looking on my desk at these two aesthetic, precisely-proportioned stone axes that I have cherished for the last 54 years, I do believe that the spirit of the society that made them — just like the axes — will endure.

I have never understood why the people of West New Guinea were so abandoned and why the Indonesians were allowed to take it over. The bloody Indonesians had just won their own freedom from their former colonial masters, and yet here they were doing the same colonising, jackbooting their way into a country with which they shared no culture, ethnicity or religious heritage. I support the right of West New Guineans to govern themselves, or perhaps even enter a union with PNG. What a pity the United Nations is so useless!

The Papuans are still fighting for their self determination and no one is interested. Keep up the great work exposing their plight and the forces military, corporate and international stacked against them.