Fifty years ago, in 1975, I was sent on assignment for The Australian to cover an Environmental Inquiry on what was then called Fraser Island.

The press and the public were invited, but only one member of the public turned up: so we two got to share a tiny tent.

The first thing I noticed about my tent-mate was the red baseball cap and his Popeye-like forearms covered in tattoos. His large, gnarled hands looked like they could wrap around, and crush, a watermelon.

His name was Pat Mackie.

Sounded familiar … and then I remembered. Pat Mackie 10 years earlier had led 4,000 miners from 40 countries in a nine-month Mt Isa Mines strike in Queensland which almost broke the company.

As we unrolled our swags on the sand next to each other it all started to come back.

Mackie, now 60, had been a member of the infamous Wobblies – the Industrial Workers of the World – and also a member of the Seafarers Union in the USA, where he’d learnt all about strike tactics.

The national government in Canberra said “Pat Mackie” was just one of his pseudonyms and had tried to deport him, claiming he had done time in prisons overseas. But he always outsmarted them.

Queensland Premier Frank Nicklin described Mackie as a Communist and “a vicious gangster”.

So that first night I lay in our cold tent next to him in the depth of winter thinking of those powerful arms and knotty hands – the ocean wind off the Pacific howling outside.

I slept, but with one eye wide open.

Canberra’s Environmental Inquiry was headed by two southern Commissioners (a lawyer and an engineer) ... assisted by four scientists, experts in different fields.

These six men never shared our tents or four-wheel drive because they had to “remain at arm’s length from all other participants”.

After all, this was a Court.

Because the state of Queensland was pro sand-mining and logging the island, and Fraser Island was their Crown Land, the Canberra Commissioners had to convene their Inquiry on a tiny hilltop station where a lonely federal communications antenna sat atop a tiny piece of commonwealth land.

Trestles were set up on the sand, the Inquiry was formally declared open, and within an hour we set off into the — at least for most — unknown.

I knew it wasn’t going to be easy.

There were no roads on this island: just the 90-mile long beach and bush tracks to the interior so rough that the bouncing of our Land Rover broke the eggs inside their cartons.

Fraser Island (recently re-named by its Aboriginal name of K’gari) is 16 miles wide: the largest sand island in the world with perched lakes hidden out of sight like opals in the sandhills high above sea level; rainforest growing vertically out of sand like arrows made for Robin Hood; and pristine creeks flowing from the tops of huge sandhills like curving slippery slides made for giants.

This fresh clear water never stops because the sandhills fill with water which slowly leeches out. Astonishingly, they act as an upside-down dam.

So here we were in a courthouse with no walls: squeezed between the Pacific Ocean and the rainforest; next to a pounding surf beach under glittering stars. So numerous that the Milky Way really did look milky from here.

The job of the two Commissioners was to decide if sand mining and logging should continue on this island which runs north-south just off the coast of Queensland 150 miles north of the capital of Brisbane. My home town.

Next morning, as we packed up camp Pat Mackie—still in his red cap — turned out to be a sensible, well-read bloke who had worked with those large arms all his life: atop the ocean waves, below the earth in mines, and now painting houses in Sydney.

He’d educated himself by reading.

“I came to this Inquiry after reading your articles in The Australian on what a phenomenon this island is. It sounded worth saving so I thought I’d attend … seeing as they invited the public,” he said. “And no matter what they say about me, I am a member of the public!”

Mackie said he had been shocked on arrival in Queensland in 1964 to work in Mt Isa to find that the miners had to have cold showers: that was why he called the strike. “You didn’t have to be a communist or a gangster to think underground miners need a hot shower after work.”

And he wasn’t the only infamous or famous Australian suddenly interested in Fraser Island. Spike Milligan wrote a letter to The Australian from London about an article I wrote on the loveliness of Fraser. He questioned why it was being mined.

And Patrick White wrote to the paper too.

By a stroke of luck, I’d had a week’s holiday on this Island in December 1972 when few had heard of it.

I was with some Hervey Bay High School teachers and my Norwegian girlfriend, whom I called “Miss Norway” (until the local newspaper turned up to interview her … having heard that “Miss Norway” was visiting Hervey Bay).

My schooldays mate Rod Lesina, and his wife, Helen, owned a Land Rover: the only way to cross that island of sand … so when it became news three years later, I already knew how breathtaking it all was.

We’d walked through high gullies of sculptured coloured sand; up a mountain of white sand; climbed Indian Head feeling like we were on a cruise liner in the Pacific; crossed a desert valley to emerge above an inland lake with a beach one side and thick rainforest the other; stood waist deep in the ocean catching fish with every throw of the line; dived under the reddish water of the suspended Lake Boomanjin to look up at a pink sunset directly above; walked out of summer heat through the middle of rainforest on a wide, soft, foot-deep path of clear cold water beneath the overhead canopy.

If there’d been a coin on that white sandy bottom I could have read the year it was minted.

And all this with no other people or vehicles around.

No dingoes that we ever saw either — just a few brumbies.

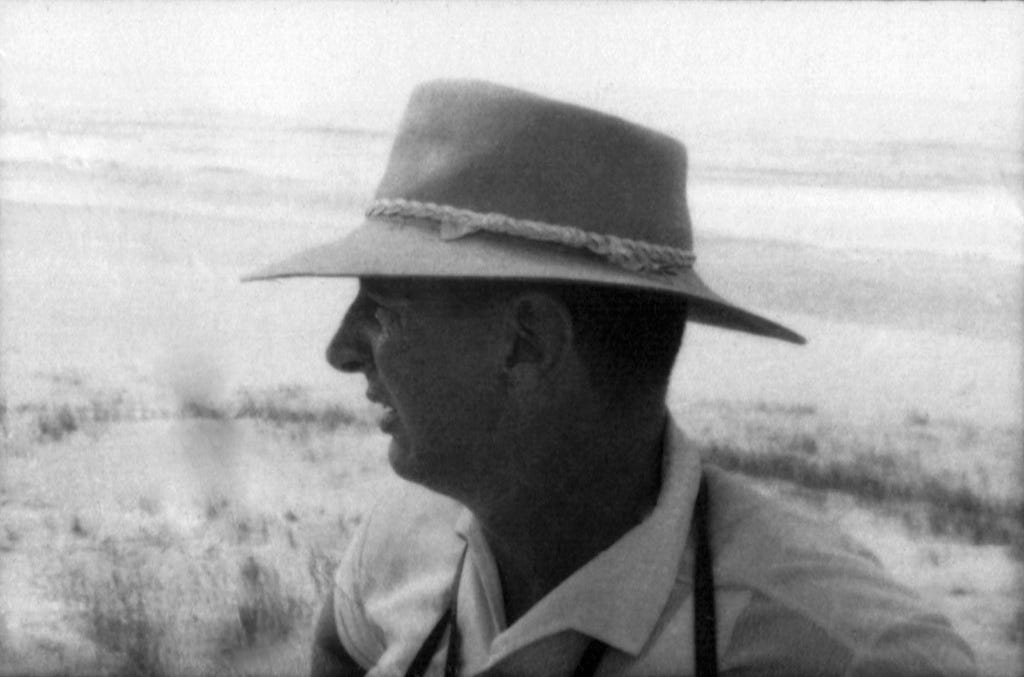

The most interesting man at the Inquiry (besides Pat Mackie) was almost unnoticeable.

He silently and efficiently put up the tents and took them down. He lit open fires for meals and cuppas. He contrasted markedly with the southern Inquiry team in their long trousers and shoes and, on some days, ties!

As the Inquiry trudged through the deep island sand, this man, John Sinclair — like me in his mid-30s — led the way in bare feet, a pair of shorts, an unusually broad bush hat, and a big knife slung on his hip like a six-gun.

He looked, and acted, like a huge boy scout.

Sinclair seemed always to be chopping firewood, digging holes for lavatories, pouring petrol in vehicles, or lighting lanterns for the southerners.

This was obviously much more his environment than theirs: or even ours.

He was an adult education officer in the mainland local town of Maryborough and had — by sheer effort of work and will — forced this Inquiry after six years of battling international sand-mining companies and local forestry businesses.

One group wanted riches; he wanted richness.

Sinclair had started the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation in 1970 using the emblem of a bulldog named FIDO.

He’d decided to take on these sand-miners after discovering that mining leases had been granted on Fraser without people being properly informed. “Oh, they did put in one miserable advertisement giving datum pegs and compass bearings in a way that people would never know. Thus there was no hearing for the first leases in 1966,” he told Pat and me.

“The public interest was not even considered.”

After that, he appeared at every Mining Warden’s hearing. Twice FIDO’s friendly barrister was unavailable and, with no money, Sinclair took on the job himself: once, in August 1973, he cross-examined sand miners in the Warden’s Court for three successive days.

To try to stop him, the Queensland government amended the Mines Act to make any objector liable for the costs of the mining company should they lose.

“I declared myself bankrupt so that I could keep objecting to new lease applications,” Sinclair told us.

FIDO caused so much fuss that Canberra eventually sent these two Commissioners north to inspect the whole of the Island for a full week before holding a two-month public inquiry on the mainland into “Fraser Island land uses”.

This happened after Sinclair won an appeal in the High Court of Australia against a local Mining Warden’s decision to allow five new sand-mining leases on this magical island. He had lost in the Mining Warden’s Court; then lost again in an appeal to the Queensland Supreme Court; but, just like a bulldog, he hung on and wouldn’t let go — and won in the High Court.

Staggering, when you consider it was decades before Green and Teal political parties won seats in Australian Parliaments. And all achieved in the most conservative state in Australia: a state that depended on cattle, sheep, and coal to balance the budget.

Dr Bob Brown, of course, was also highly successful in the state of Tasmania. But none was so unlikely a green hero — or started lower to finish higher — as John Sinclair.

He looked, dressed, and talked nothing like a protestor.

In fact his background pointed in the exact opposite direction. Sinclair was a third-generation Maryborough boy who left school at 15: a Country Party member, a Mason, and a Scout leader who wore his hair short-back-and-sides under that broad-brimmed hat.

Anxious to get ahead, he’d boarded for three years 100 miles from home at Gatton Agricultural College to get a Diploma in Agriculture. Then, at night, he slowly, but doggedly, completed an economics degree at Queensland University by correspondence from his front verandah in Maryborough.

In 1962 he married Helen, who had been in the same year as him at Maryborough High.

By 1969 John Sinclair was considered Maryborough’s brightest young son and was sent as a Rotary exchange student to the United States to see things anew.

Something the town later regretted.

By the time I met him on Fraser Island, John and Helen Sinclair and three young sons lived in a little wooden Maryborough house. John drove an old 1957 FJ Holden. He ran his FIDO campaign from the dining room table which, when I saw it later, was blotted out by piled letters of support – and small cheques.

Reflecting during a long winter’s night by a fire next to our tent, he told Pat Mackie and me that he had been warned many times to stop his campaign and had suffered “many painful moments”.

For example?

One day he was driving into town with his three sons in his FJ when they saw a huge blackboard sign outside the garage. On it was written with chalk in large capitals: SINCLAIR NOT SERVED HERE.

He was upset that his sons had seen it.

But his worst moment was at the annual Maryborough Show. He led his young Scout Troop as they marched proudly into the ring … only to be loudly booed by the crowd.

Pat Mackie was impressed by that. “The mark of a man is what he can take,” Pat contributed.

John Sinclair could certainly take it.

He was built more like a bullock than a bulldog: six foot tall and a fit 16 stone with a massive head like a tomahawk — big nose slicing forward. His face more a statement than a question. He needed to be tough, very tough, to preserve an island that was like a tiny violet in the huge but harsh Australian landscape – a landscape which for 200 years had been seen as a resource.

This toughness brought him deprivations few political crusaders have suffered.

Maryborough people, not unnaturally, saw the sand-mining and timber-getting as the town’s only real future – they depended on it for jobs – and so to them Sinclair was a threat.

Worse, he was Maryborough born and bred with his parents and aunts and uncles in the town. Later he was to write: “My dad Charlie was particularly hurt in ways that were not deserved. He was forced out of the Forestry Department for no other reason than he was my father.”

John Sinclair began his campaign for Fraser Island by producing his own tiny monthly newspaper.

Then came the Fraser Island song. Written and sung by a Brisbane couple, it was pressed as a record in 1971 and sold out. Later, when the issue became national, Sinclair organized a re-press. The haunting lyrics included:

Who will rip this land apart?

Who will sell my soul?

How many bidders are waiting in line

For the promise of easy gold?

Who will tear my timber down

And leave my wildlife dying?

Is there no one left to care for me?

My name is Fraser Island.

Soon he began issuing media releases like a professional public relations agent. This evolved into a four-page supplement in a local paper: he posted copies to FIDO members and conservation groups throughout Australia.

There were pictures of felled trees and deep sand-mining pits with provocative headlines like: Fraser Island: Priceless Pearl or Political Pawn? All accompanied by maps of sand-mining leases (with lease numbers) and forestry operations. He even listed such things as sand-mining company staff changes. Bulldozer sizes. Rates of sand-mining. The extent of subsidies to timber millers.

One night, by the light of a lantern in our tent, Pat Mackie asked Sinclair how much danger he had been in – something that had never occurred to me, so I quickly started taking notes.

“Early on there was an ugly meeting in Maryborough where my position became so dangerous that old friends and relatives warned me not to speak.” He looked around the Town Hall, and didn’t.

When more than 1,200 turned up for a similar meeting in Maryborough a year later in 1975 “even our then family doctor and our chemist took snipes at me in an unprofessional manner”.

“Did you lose any friends in your home town?” Pat Mackie asked, knowingly.

Sinclair bowed his head and the tent went more silent than before ... but then the bulldog re-emerged: “My wife lost her best friend over this ... The friends I have lost … I no longer regard them as having been my friends.”

“Your job was in danger too, I bet,” said Mackie.

“Yes, the state government is my boss. So some people tried to have me sacked from the Education Department. At one stage at home we received so many abusive phone calls the family were scared to pick up the receiver.”

Yet the bulldog didn’t back off.

To get more supporters he organized cheap safaris to the island to show people its “Beauty Spots” … so many of these that they were signposted and actually numbered.

Almost invariably he won a truckload of converts.

This was how Sinclair got Dr Moss Cass, then Gough Whitlam’s Minister for Conservation in Canberra, to see the island ... which led to the Inquiry we were now following.

When the sand-miners and forestry workers showed the Inquiry Commissioners their various operations in the best possible light, only John Sinclair was on hand to try to poke holes in their arguments.

Surprisingly he never once got angry.

“I don’t know how he does it,” Pat whispered. “I wish I could have done that. The strike might have been settled six months sooner!”

Sinclair was more inquisitive than aggressive … answering rebuffs only with more difficult questions.

Take the day the sand-miners showed the Commissioners an “experimental rehabilitation plot”.

While Pat Mackie went over and shook hands with all the workers, a company spokesman explained to the Commissioners that the land had been first cleared, then burnt, and a foot of topsoil removed. The topsoil was kept for a month and then respread and fertilized.

Now, many plants and bushes were growing for us all to see.

A scientist employed by the sand-mining company showed where insects had returned to the trunks of bushes that were once their home.

It was impressive.

Then up spoke John Sinclair: “I would point out that the heaviest applications of fertilizer were put here at the top: so now let us move through to the back to see the poorer parts!”

There he jumped up on a huge tree stump and – as sand-miners around him seethed – addressed the Inquiry like an orator: “It isn’t as if this land has been sand-mined! You will notice there are lots of tree stumps -- which means a total removal of topsoil was impossible and therefore it is not a good reproduction of [rehabilitation after] sand-mining.

“The biggest difference, I would argue, is that the bed of sand beneath was not disturbed as it is in sand-mining to a great depth when the minerals are removed.”

It must have been difficult for these sand-miners to accept Sinclair into their midst at this time. He could potentially cost them untold millions of dollars. Dillingham-Murphyores had export licences for only two of their leases — and these alone involved contracts then worth $43 million.

When the foresters showed the Inquiry their handiwork they passed a burnt-out patch in a rainforest area.

Sinclair: “Is this one of your deliberate fires?”

Forester: “This was a wildfire. Check your facts.”

Sinclair: “Was it to eliminate satinay and encourage blackbutt?”

Forester: “No, we don’t burn satinay [a giant rainforest tree]. It was a tourist fire. I don’t know if it was a FIDO fire.”

Sinclair: “Is it not true that eucalyptus like blackbutt are favoured [propagated] by fire, whereas rainforest trees are not?”

Forester: “A fire would occasionally be necessary to retain them as eucalypt types. This forest would be heading to a climax as a rainforest form. We are holding the forest in its present condition.”

Sinclair: “Holding back nature?”

Forester: “What is nature?”

Pat said he was watching the Commissioners: “I’m sure I saw one of them raise their eyebrows!” Whereas I was looking up at the canopy of huge rainforest trees thinking: “Why aren’t we talking about them?”

So I asked the chief forester there – a man whose broad back was an axe handle-and-a-half wide – how much the straight, tall tree next to us was worth?

He said: Where? Here or at the Mill after we ship it to Maryborough?

Me: The Mill.

He looked up and started estimating aloud as everyone waited.

He said: …Super feet, …super feet, …super feet … about $20.

Me: Then leave it. It’s worth more here.

His wife who had been standing off to the side sauntered over and asked if I was “the Hugh Lunn writing in The Australian?”

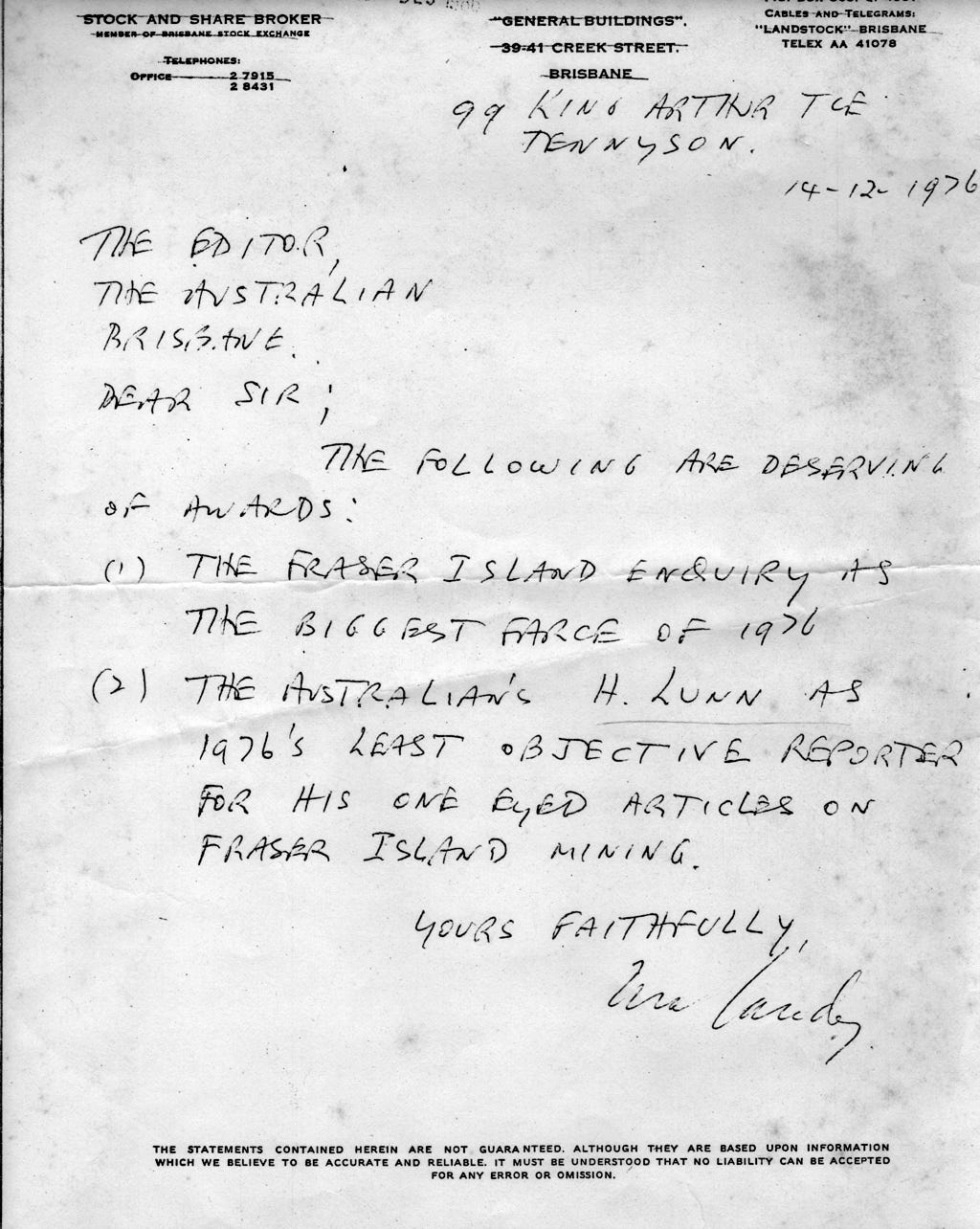

I was a bit cagey because my paper kept getting a stream of letters with what was then a very pejorative address written on them all: “Mr Hugh Lunn, Environmental Editor, The Australian”. I’d never had that title – in those days no one did.

She started accusing me of writing lies and said that, because of me, southern tourists were arriving in Jaguars (of all things) at the ferry to come over to see the island.

I couldn’t answer back: not with the axe handle-and-a-half standing silently nearby watching intently.

Sinclair was unhappy at the direction the Inquiry was going.

He wanted more time spent at the “Beauty Spots”. But the sand-miners and foresters kept the Commissioners moving to see the good work they were doing. This meant every day bouncing slowly along bumpy sand-and-root roads huddled inside Land Rovers.

Sinclair told Pat and me: “The miners and foresters are trying to exhaust the Inquiry so they won’t get time to appreciate the beauty of the island.”

Also it was mid-winter: not the best time to appreciate a sub-tropical paradise.

So I was glad when we finally got to beautiful Eli Creek – which rushes down in cool curves through the sand from the hills all the way out onto the beach. But when we got there, I could see this six-foot-deep rush of cold fresh water didn’t look anywhere near as inviting in June as it did in December.

So I did my part for Fraser Island.

I stripped down to my Y-fronts and announced: “Pretend it’s a stinking hot summer day!” – and jumped in to be swept downhill by the rushing water as though swimming very fast – yelling “like Shane Gould” – as I sped past the Commissioners.

I wrote of this in a column in The Australian – whereupon the local state member, Gilbert Alison, stood up in Parliament and declared: “I saw Hugh Lunn wrote about jumping in to Eli Creek in his Y-fronts, whatever they are. He should hang up his Y-fronts and his pencil, he’s not worth two bob.”

At the end of the week, Pat Mackie and I sat John Sinclair on a log and asked him to explain why he was going through all this … when the odds were he would never succeed.

He thought for a moment before speaking, then looked off into the distance.

“Whenever I wonder if it’s worth the struggle, I just have to spend an hour at Wabby Lake, or stand for a moment in Rainbow Gorge,” he said. “Some places have a magic which revives and gives new energy. You just feel as if you have communicated with your soul.

“There are many places here which are like cathedrals and give a feeling of renewal. Did you notice how when we walked back from The Enchanted Valley today not a soul spoke?

“Nobody even wanted to.”

One thing in particular that worried Sinclair was that the lakes perched high above the sea on crusty sand would drain away if the foredunes were dug up.

On the last day he led everyone on an hour-long hike from the beach into the sandhills to Wabby Lake. This lake is up to 100-feet deep with a white sandy beach one side and rainforest around the rest.

After 20 minutes of walking through ferns and bush, we emerged on a desert stretching and widening before us as through an arch: in the middle some yellow sand, to the right some brown, and far off a rising patch of brilliant white.

There were a few lonely, stark sentinels of what had once been mighty trees — now etched to delicate vertical driftwood by the ceaselessly moving sand.

We struggled up that open blow to eventually emerge atop a sand dune and looked down on Wabby’s green lake: as unexpected as finding the Mona Lisa in a School of Arts Hall.

Pat Mackie wondered what it might cost to try to reproduce such a scene.

Fraser Island was certainly irreplaceable.

The yellow-red sand pinnacles worn to a knife-edge by the winds; the Aboriginal middens marked by the piles of eugarie shells (local name: wong); the natural champagne rockpool north of Indian Head; the black tortoises at Lake Bowarrady (Beauty Spot No 44) that come out of the water to see you.

As I bent over to say hello one nibbled on the zipper of my yellow Harrods raincoat.

And best of all, Woongoolbver Creek, which leads like a safe white footpath through dense rainforest, past palm trees straight as spears — enclosed overhead by the jungle. The sandy bed covered by a foot of clear, cold water. Within the forest is the anglopteris fern: the oldest living fern in the world.

But John Sinclair and Pat Mackie don’t walk there anymore.

Pat Mackie headed home to Sydney, stopping for a few days in Brisbane with me and Miss Norway at our Indooroopilly home. Not a gangster at all.

The Inquiry had left the island and re-convened in nearby Maryborough, where John Sinclair — protected by legal privilege — spoke out robustly against the sand miners. This was reported in the media. However, when he printed his court statement in his newsletter it was not protected and he was served with a defamation writ for $290,000.

The next year, 1976, the state government transferred Sinclair 150 miles away from his home-town of Maryborough to Ipswich after the Canberra Inquiry banned the export of mineral sands from Fraser Island.

The Australian a few months later named John Sinclair Australian of the Year.

John Sinclair went on to more adventures which he recorded in a memoir he wrote himself: Saving K’gari published by FIDO.

In 2016 he was invested as an Officer of the Order of Australia at Government House in Brisbane with Helen and their three proud sons present.

They should have put a blackboard sign outside:

SINCLAIR

NOW

SERVED

HERE

P.S. John Sinclair's collection of 800 Island photos is managed and curated by Sunshine Coast University as K'gari Research Archive. Search here.

Dear Hugh,

This is the most wonderful story that i feel you have ever written! I’ve always known some of the details but never to this extent and your descriptions of the island simply marvellous. Thank goodness for pioneers like John Sinclair and that he was eventually rewarded for his courage and the Island is preserved for generations to follow, kind regards Roger ps thanks must go to you as well for your long term vision to understand the significance of stopping the commercial development there at that time.

gday Hugh

splendid story and pix on your Fraser Island adventure.

Your work gets even crisper and sharper as you age.

You might be sheltering under a bed or in the cast iron bath tub from a cyclone right now, but you might like to know you still one old phart appreciating your skill on this side of Gondwana.

intrigues me that you somehow have all these pictures in this century. Have you lugged them through life in a bloody big portmaneau on wheels?!

In your list of exotics, do you have Harry Reade(?) and Charlie wright known for a few years for his orange outfits? is liz Johnston still on deck curating those heritage-listed legs?

He said sexistly

And reminding you of the unwritten book of Owen Thomson atrocities.

ooroo Georgew