In November 1979, out of the blue, a Sydney head-hunter rang to ask if I would join Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s staff to write all his speeches.

I refused immediately, saying, “But he’s a terrible speaker!”

The head-hunter, Helen Gill, a former Brisbane journalist, was too smart to be put off her job by my gut reaction.

“What you've picked up on, Hugh,” she replied, “is that the PM's speeches have been written by a committee of three – and they read like they’ve been written by a committee.”

“But hold on, Helen,” I replied, “I’ve seen Malcolm Fraser speak. He’s no Gough Whitlam. He bores everyone to tears. He drones on and on. He hardly ever looks up at the audience. I don’t think a speech writer is what he needs … Fraser needs a double!”

The journalist in Helen came back like an elastic band.

“If his delivery is that bad, then there's the greater challenge for you. This is why he’s looking for just one writer not three! He’s very impressed that you have won the Walkley Award for feature writing three times in the last six years … and from Brisbane, of all places!’’

I was having none of it. But Helen wasn’t giving up.

“It will be a feather in your cap; it will look great on your CV; and it will be something you can tell your grandkids: how the Prime Minister of Australia needed you and sought you out to write his speeches.”

She was laying it on a bit too thick, but then she pushed one of my buttons.

Helen said I’d be crazy to knock back a Free First Class Trip to Canberra. Well, I didn’t want the job, that was for sure and certain, but it did gnaw at my soul that in 20 years of journalism around the world I’d never once flown First Class.

In actual fact, I was going to the national capital the following week to collect a National Press Club award: “Best Sports Feature of 1979’’ for “The Battle of Ballymore’’, about a Rugby Union match between Queensland and New South Wales. But, of course, they’d sent me an Economy Class return ticket.

So this was my chance to sit up the pointy end of the aircraft with the hoity toity, after a lifetime of being one of the hoi polloi stuck down the back. While First Class were allowed to leave first, the rest of us would be kept back, jostling and crushed at the dunny end waiting half an hour to get off.

So I accepted.

At the Prime Minister’s office in Canberra – the city where the entire population has been screened through the public service interview process – I felt surrounded by Malcolm Fraser and Liberal Party Director Tony Eggleton. They sat closely on either side of me in lounge chairs in one tiny corner of his office which was the size of my house … as if we were meeting in secret, or all in need of hearing aids.

It was as if they were sealing me off from all escape. No one could help me here.

The six-foot-five-inch Fraser on my dexter side poured coffee from a silver pot and talked in whispers. But what was making me nervous was the small man on my left: Tony Eggleton, the brains behind the Liberal Party. A journalist himself, Eggleton had been press secretary to three Prime Ministers: Menzies, Holt and Gorton. Now, as Campaign Director, he’d delivered the Liberals two massive election victories over the former Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

Eggleton sat staring at me from my sinister side: black hair, dark sad eyes, and pale heavy jowls. For some reason, he seemed to be treating me with suspicion. Then he spoke: “So why do you want this job, Hugh?”

I nearly ran out of the building.

Helen Gill had assured me: “Of course, you don’t have to take the job, just be interviewed for it, happens all the time, have fun, there’s no compulsion either way.”

She made it sound such a good idea back in Brisbane... but Helen wasn’t here. I was in way too deep. And I wasn’t having fun.

It suddenly dawned on me that I was playing a role without any acting experience. I was, in fact, The Great Pretender. I had absolutely no intention of taking the job: but Fraser and Eggleton didn’t know that – and they didn’t seem to want to know it.

I’d seen The Platters perform at Milton Stadium in Brisbane and their words started echoing in my ears … “Oh-oh yes, I’m the Great Pretender, pretending that I’m doing well, I seem to be, what I’m not, you see…” it was like my theme song. I was now humming it.

But the more I hummed and dithered, the more these two most powerful men in Canberra determinedly and enthusiastically pursued me like a cornered fox.

Although he didn’t know it, I’d met Fraser 12 years earlier – in 1967 during the Vietnam War. He was visiting Saigon as Minister for the Army and, as a Reuters correspondent I was sent to the Caravelle Hotel to interview him. As I did so Fraser paced around his room, impatient and reluctant to answer questions. We were two Aussies in the middle of a war in a tropical foreign country in the steamy heat, but that didn’t melt his ice.

It was an experience neither of us enjoyed.

As the PM droned on, pouring from another pot of coffee, I was reminded of the next time I saw him,1975.

Fraser had arrived like a hero in Brisbane as the Liberals’ great tall hope to defeat the Labor Party's popular Gough Whitlam, the “socialist” ogre who had already knocked off two Liberal leaders at two successive elections.

More than 500 Brisbane businesspeople had paid $20 a head at Lennons Hotel to hear him speak and, as Queensland editor, I wrote a long descriptive piece for The Australian about their night of frights:

We had read much of this man, a big man with a bigger reputation. The next Prime Minister of Australia … a man who, perhaps significantly, stands a forehead above even Whitlam. But what we hadn’t heard was that Malcolm Fraser is, let’s be fair, a poor speaker … he cannot stir a crowd, even a willing, excited crowd … The businessmen roared like a football crowd at the start … but as the speech wore on the room fell silent. Fraser used no emphasis, showed a lack of truculence at key points … As he read his speech with the light reflecting in his rimless glasses, making him look blind, Fraser fell into a dreary monotone… Good lines came and went before anyone realised a point had been made … A Queensland Liberal looked across the table at me and rolled his eyes like a man looking at his partner as their racehorse finished last.… Eventually there was an embarrassingly lonely “hear, hear’’ when Fraser said something like “I will abolish Medicare.” “Well I’m glad somebody's listening,” the PM said, suddenly realising he had blown the wind out of his own sails.

This story went to Sydney by telex and when it hadn't been published after a few days, I rang the features editor Nic Nagle to ask what had happened.

“The last time I saw your story,” Nic said, “it was hanging out of the editor’s hip pocket and he was flying to Canberra.’’ I had an immediate vision of Rupert’s friend and my editor Bruce Rothwell, with his usual red tongue of pocket square poking out of his coat … and a long white tail of telex paper hanging from his trousers.

I guessed that this office, where I now sat cornered looking for a way out, was where my never-to-be-published story had ended up. Perhaps it was the reason I was here.

Tony Eggleton spoke again.

“When can you start?”

“Well… I’ve got a good job,’’ I said.

The Prime Minister replied: “I’m sure Rupert won’t mind lending you to me for a few years … to have one of his journalists working in the most important office in the land.’’

“But… I’ve got a house in Brisbane…and I’ve got a car…” I blurted.

Fraser responded: “Look, what you don’t seem to realise is that this job will lead to an overseas posting.”

Tony Eggleton: The U.N.

Fraser: Geneva?

Eggleton: New York.

Fraser: In a couple of years.

Eggleton: Your future would be secured.

The answer came to me unexpected.

“But I want to live in Queensland,” I countered. “All my family live in Brisbane. I’ve got a tennis court in my garden. I play competition twice a week for U of Q.”

Fraser: We’ll arrange membership for you here, and you’ll have reciprocal rights ...

Eggleton: Kooyong? White City?

Fraser: South Yarra.

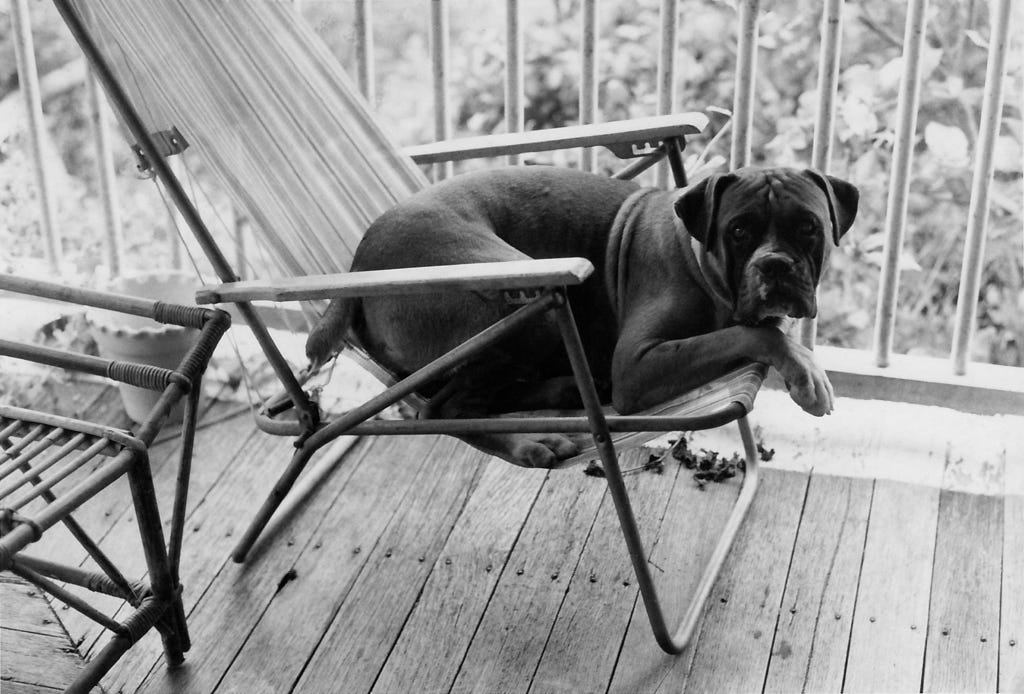

“Err... I also have a boxer dog called Bazza … he’s named after Bazza McKenzie.”

Fraser reacted to this filibuster by leaping up from the low lounge chair to summon a public servant to his office.

When this poor fellow arrived he didn’t even get into the room because Fraser was waiting for him at the door: “This speech-writer says he wants to live in Brisbane. Can he do that and we fly him down every time he needs to write one of my speeches?”

The public servant vacillated and stuttered and hesitated … until Fraser boomed: “Good, he can then” and shut the door in his face to signal the fellow was dismissed.

I wished he’d left the door ajar.

“That’s settled then,” Fraser said as he returned to the lounge chairs. “You will fly down whenever we need you. Write the less important speeches from Brisbane.’’

I now understood that mysterious line from the song The Great Pretender: “Too real is this feeling of make believe.”

“I’m in a relationship with a beautiful Brisbane girl!... I’m 38 and a bachelor…I’ve got high hopes that this will, given the effluxion of time…

Eggleton: You’ll do all your research up there…

“…develop into a permanent relationship...”

Eggleton: We’ll supply all the materials and any typing you need…

“You two will be interested to know that her uncle was press secretary to Sir Robert Menzies!”

Eggleton: I will be briefing you.

“Plus there’s my tortoiseshell pussycat Turtle. Bazza and Turtle sleep together in the same basket!”

Eggleton: Take all the time you need.

When I reached the door, backwards, I said I’d definitely be thinking about it.

I absconded from the PM’s office … escaped out the front door of Parliament House … and fled on foot through Canberra, which no one ever does because there are no footpaths, only roads.

When I reached Canberra Airport I was no longer The Great Pretender, but I was “just laughing and gay like a clown”.

I never rang them. They never rang me.

My flight from Canberra set Brisbane school teacher Alan Jones on his incredible career path. Malcolm Fraser hired Jones – an accomplished speaker himself — to write his speeches and so Alan Jones became part of the national political discussion … while I retreated back home (First Class) with my Sports Feature Award tucked under my arm … back to the verandah on my Queenslander, to my tennis court, to my girlfriend, to Bazza, and to Turtle.

A happy man again.

Dear Cackles, Ican hear you laughing from here.

I don't know Damian but I reckon I could write a good sitcom -- if I only knew how!

At the moment i'm writing for my substack page and converting "The Great Fletch" into 160 episodes as a radio serial. Spike once wrote a letter to ed about one of my articles ('70s). I was chuffed.

Best place to buy my books is from me! (see my website) or you can get a lot of them as eBooks from Amazon or from HarperCollins. But they haven't got my Behinad the Bana Curtain or my JOH - The Life and Political Adventures of Johannes Bjelke-Petersen which have just been re-published and for sale on Booktopia (I've got a few).

Some -- like On the road to Anywhere and Queeenslanders are out of print. And "Four Stoires" published by the Aboriginal Treaty Organisation is lso out of print. I've got the only copies left of "More Over the Top with Jim". Head Over Heels is the second part of HC's "Big Book of Lunn". etc etc

I think Fraser would have remained exactly the same forevermore -- but then Gough befriended him!

Thanks for your nice comment,

Hugh

Loved the telling of the story. The tennis court photo was a brilliant inclusion.