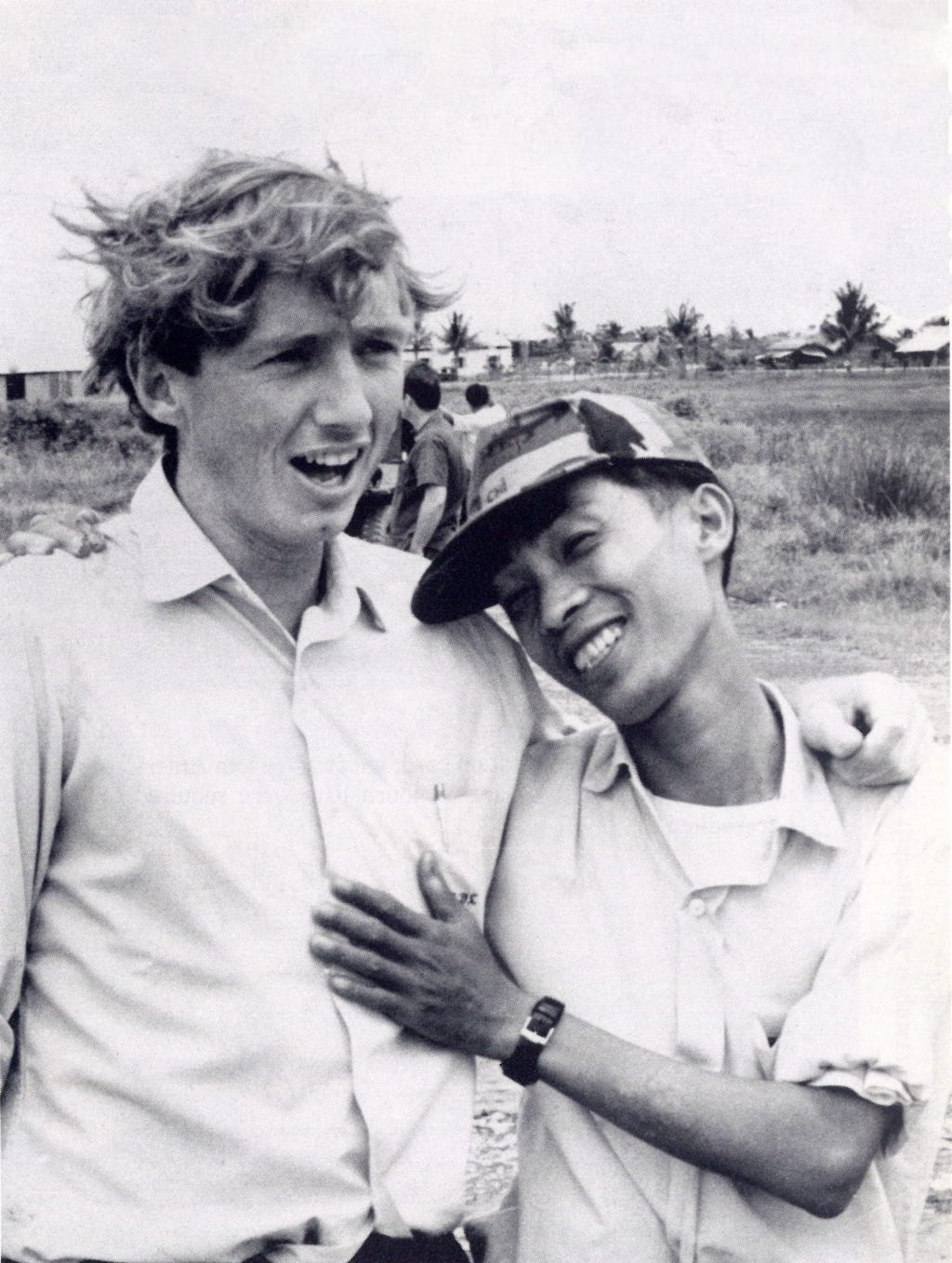

When I lived in Saigon in 1967, my good friend Pham Ngoc Dinh said a strange thing in the midst of war: “Vietnam is always too short of fortune-tellers”.

Dinh didn’t like to come to work if the first person he saw in the morning when he opened his front door was a pregnant woman: that was unlucky. On the other hand, if he saw a very old man he would immediately tackle all the most difficult tasks like re-negotiating the lease on the office or re-registering the car—tough things to do in a corrupt state.

As Dinh put it, “If you see a person with beaming face, that lucky. You see me, ‘Hello’, ‘Good morning’, that lucky. But many men with mean face, so cold, that unlucky.”

Dinh even predicted, correctly, that my Australian reporter flatmate was “not long live man” because of his “melancholy” expression.

Traditionally, blind Vietnamese could make a living foretelling the future for eager customers. Dinh’s wife, Vy, told me recently that fortune-tellers in Vietnam didn’t have to advertise back then, “they just relied on word of mouth”.

“There was no Tinder so a mother might want to know when her daughter will get married, or a father might want to know if the woman his son is marrying is good luck for him,” Vy said.

In Australia, instead of fortune-tellers, we look to the after-dinner speaker for our tall tales. And there’s never enough of them to go around either.

My first book was published 44 years ago in 1978 and since then I’ve made hundreds and hundreds of speeches. Publishers always urge their authors to be seen, one telling me bluntly: “If you don’t make public appearances everyone will think you’re dead!”

Writing the book is easier than delivering the speech.

While writing is tough work, speaking is mentally exhausting; with your manuscript you can go back time and again over the months to fix mistakes … but when speaking to a crowd you can very quickly bring yourself undone. And you can’t undo what you’ve just done in front of 300 people.

Take the night of May 4, 1990, as an example.

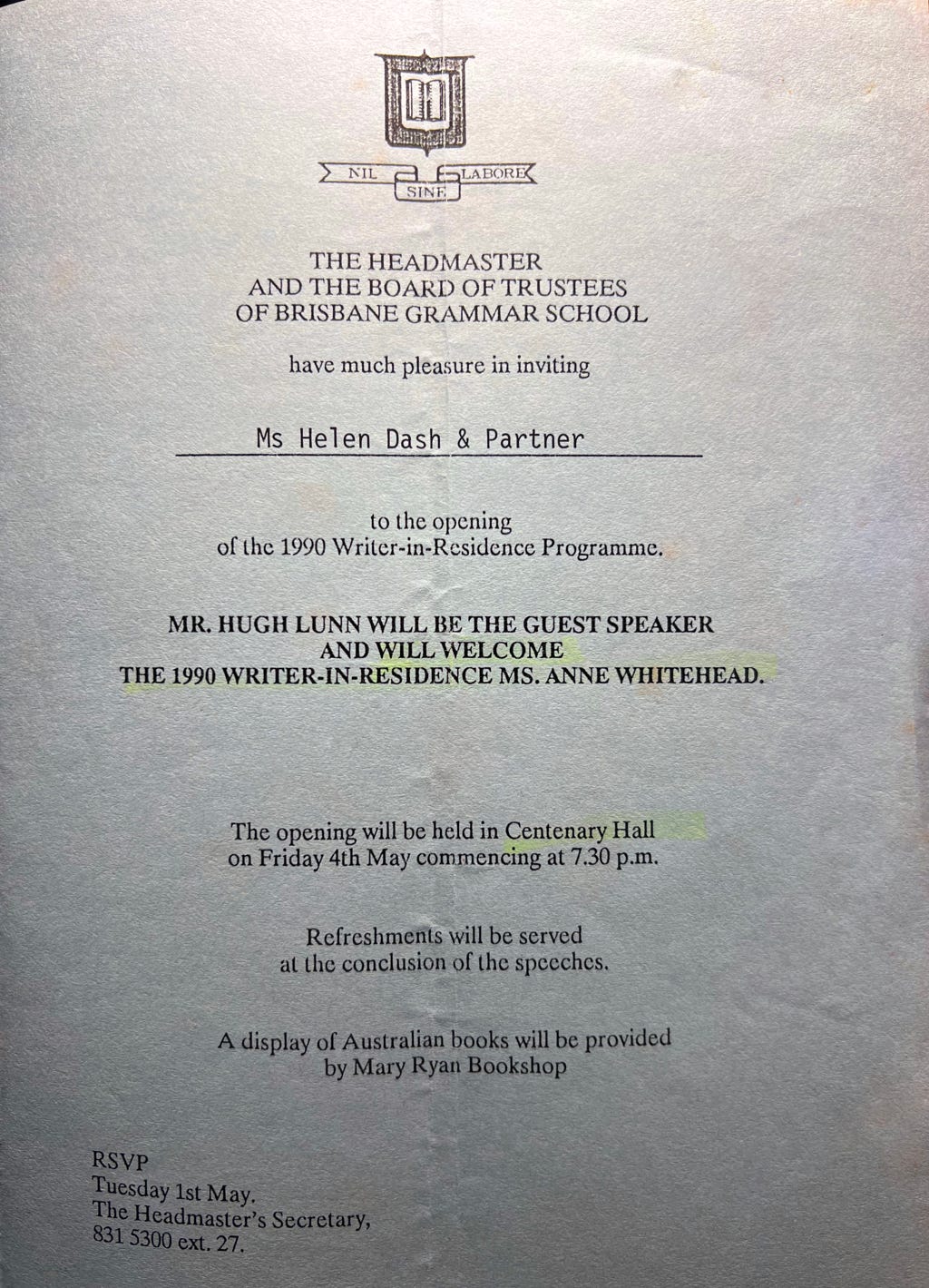

I had been very surprised to receive a letter, signed “P.G. Lennox”. It was from the Headmaster on behalf of the Board of Trustees of Brisbane Grammar School.

They were putting on a welcome for their latest Writer-in-Residence and asked me to give a 30-minute speech on the night.

This invitation was improbable because I had attended the rival opposition GPS school, St Joseph’s College, just along the ridge on the same road, Gregory Terrace, in the inner Brisbane suburb of Spring Hill. And we had always done our darndest to beat them on the rugby field, the cricket pitch, and in the public examinations.

In fact, I’d recently published a book about my schooldays including how, back then, Catholics and the majority Protestants rarely mixed. Which made for some spectacular rugby matches.

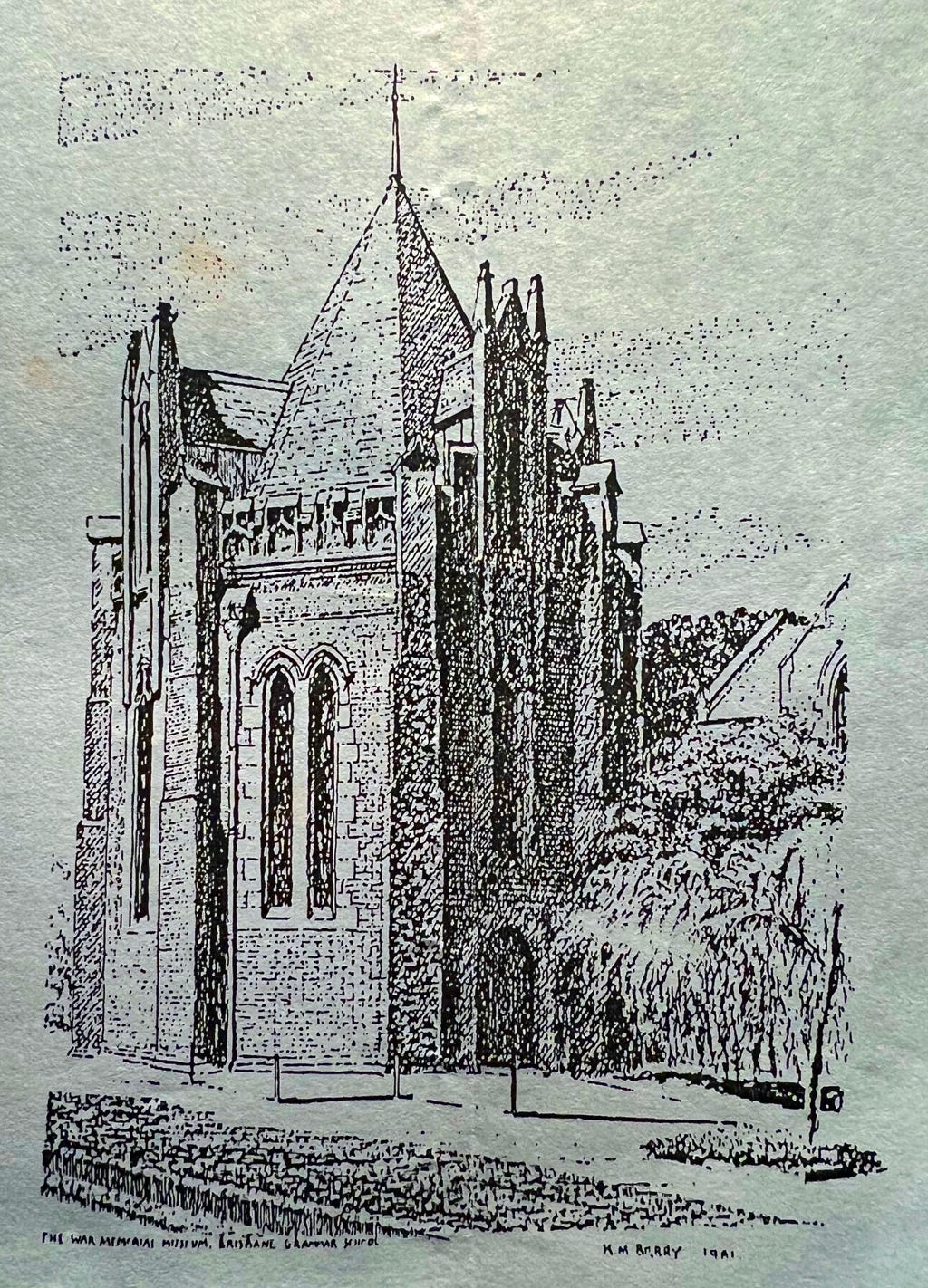

My Catholic College was started by the Irish Christian Brothers in 1875, the year before General Custer was wiped out by the Indians. You would think that would make us first, but Brisbane Grammar boasted, whenever possible, that it was founded seven years earlier than us … making it the oldest boys secondary school in Brisbane.

While our school colours were red and black, theirs were a combination of Oxford Blue and Cambridge Blue: which gives you the idea of what we were up against.

In his letter P.G. Lennox told me that previous speakers had been Ross Fitzgerald, David Malouf and Blanche d’Alpuget.

What he seemed to be saying was that I would be in elite company.

It was all going to happen in the school’s Centenary Hall. The audience would be students taking part in the Writer-in-Residence programme, their parents, interested members of the school community… and the Board.

P.G. Lennox said it would be “of value” if I could speak on “The Role of the Writer in Society” and whether the writer’s responsibility was to “educate, enlighten, or entertain”.

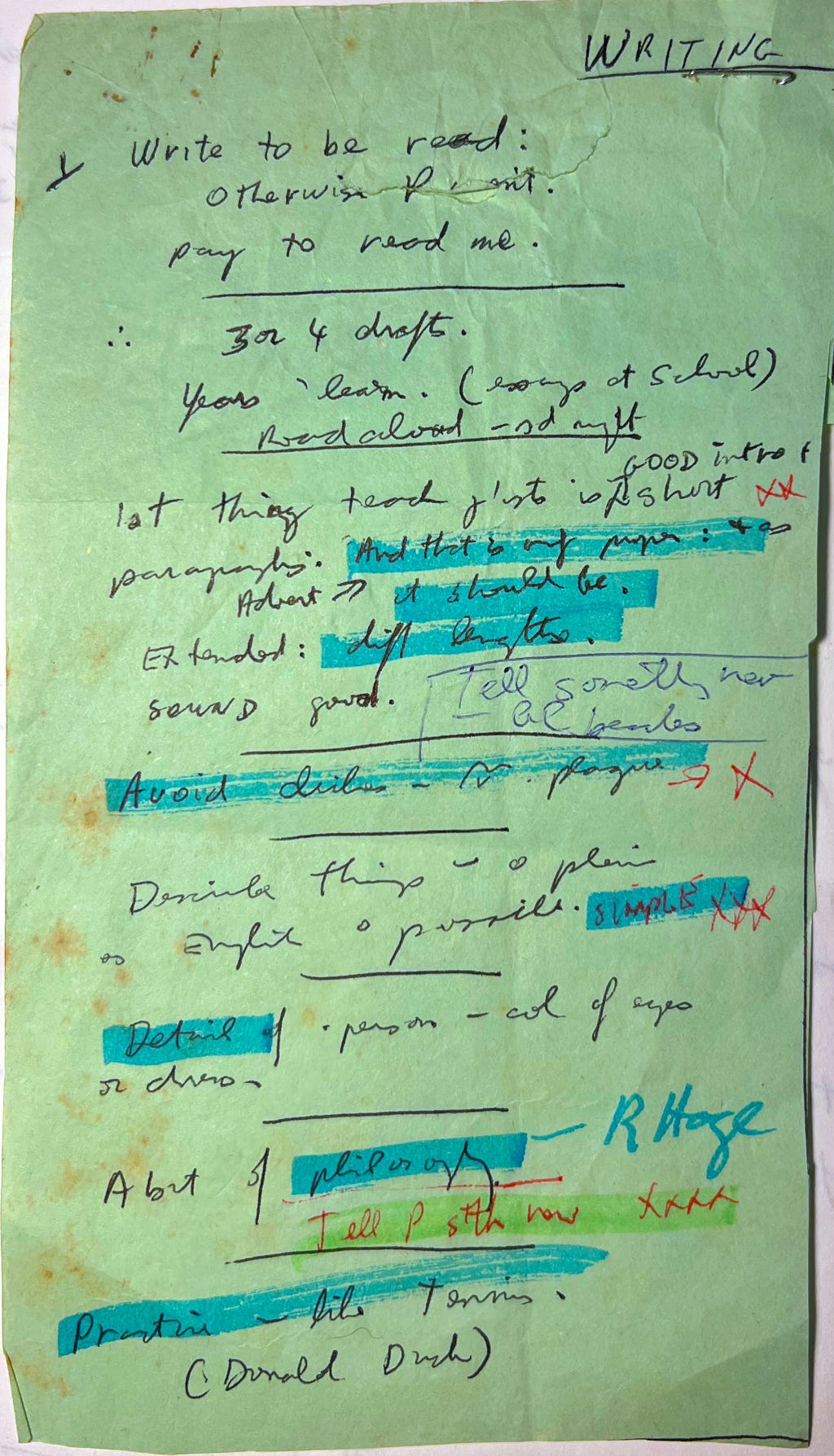

After accepting, I sat down immediately with a scrap of green paper and made some quick notes with a biro on what the writer does:

1. Write to be read: otherwise society will ignore you and you’ll have no role at all in society.

2. Therefore, think of the reader with every line … which means writing in plain English, not like Donald Duck talks.

3. Write at least three or four drafts before beginning because writing is like a girl brushing her hair: get the knots out!

4. Writing is like playing tennis – if you want to be a good player you have to practise several days a week. Don’t expect to walk onto a tennis court once in a while and play well.

5. Read your story out loud to see if it sounds right: words have sound, and length, and weight … as well as meaning.

6. If you want to be read widely, write short sentences: preferably nothing over 30 words. And make sure your sentences are of greatly varying length. It’s much easier for the reader. Avoid clichés like the plague (don’t even touch them with a 10-foot pole)!

7. Look at advertisements.

When the federal government paid a high-priced advertising copywriter to sell the idea of Medicare, I kept the advert because the message finished as clear as a pane of glass: “And that is only proper. And as it should be”.

Who can’t understand that?

8. Write what you see.

When an American marine battalion was ambushed in the DMZ in Vietnam in 1967, instead of writing the usual “45 US marines were killed today in bitter fighting after unsuccessfully trying to enter the UN Demilitarised Zone” I wrote: “American marines came out of the DMZ today carrying their dead piled high on their tanks and saying they had been ambushed”.

9. Include some of your own philosophy.

When I wrote about a baby boy born with a tumour in the middle of his face instead of a nose, I said he faced being condemned to an institution for life: “yet all he was, was ugly”. (Brisbane surgeons, in an Australian first in 1977, moved the bones around in his face and Robert is now a very successful author and journalist.)

10. Make sure you have a good start. I can’t emphasise this enough because if the first sentence doesn’t grab your audience they’ll go away and read something else. You can do this by telling the reader something new. Not like some newspaper stories I’ve kept which began: “roads are vital because they connect one town with another” and “telephones make it possible to stay in contact with each other over long distances”.

That’s not writing, it’s typing.

Having written down these notes on what turns typing into writing, I needed to address what the role of the writer was.

Then I happened to hear a government official on TV say something like:

“After objective consideration of contemporary phenomena we must negotiate, liaise, co-ordinate and manage the process with appropriate key stakeholders to mitigate against sub-optimal outcomes and other issues so that the peak body umbrella group can mentor and form partnerships in the sector to take up challenges in the wider community which will initiate consultation moving forward”.

That’s when I realised: in a society that has learned to speak nonsense, the role of the writer is to make sense of the world.

Normally I speak from hand-written notes – never-ever reading off two panes of glass from an autocue like all politicians do now. But for me this was a big occasion. So I typed up my 3000-word speech a week before the event in order to be as ready as possible.

On the evening of May 4 Helen and I dressed in our Sunday best.

At Brisbane Grammar we were introduced to P.G. and Mrs Lennox, the members of the Board of Trustees, and the writer-about-to-be-in-residence, historian Anne Whitehead.

Everyone then filed in to Centenary Hall.

The seats rose steeply up from a tiny stage like a large University lecture theatre. The place was full to overflowing and I noted with a little bit of trepidation that my UQP publisher Laurie Muller was in attendance.

Helen and I were seated together in the front row facing the podium, with P.G. on my right and Mrs Lennox on Helen’s left.

The Headmaster stood up and went to the podium where he welcomed the audience and acknowledged Anne Whitehead and other dignitaries, before adding that refreshments would be served afterwards.

He concluded: “And now, ladies and gentlemen and members of the Board of Trustees, I’ll hand over to Brisbane author Hugh Lunn who will be addressing us on The Role of the Writer in Society”.

Everyone applauded as I proudly leapt up to take the podium and enjoy my moment: a Catholic from St Joseph’s Gregory Terrace about to shine in the Brisbane Grammar sun. I’d come a long way from failing exams at Mary Immaculate Convent on the working class southside of Brisbane at Annerley.

I reached for my speech ... and, and, and … it was only then that I realised, my speech … it was still sitting in the middle of our Queen-sized bed back at home where I’d carefully placed it away from all dangers. I could see it there clearly: beautifully typed, large letters, numbered pages, a few last-minute improvements.

My mind was racing as P.G. Lennox again ushered me forward with outstretched hand towards the podium as the applause began to die.

There was no time to go home and get the speech from the bedspread … No way now of putting off this appointment with destiny.

I would just have to wing it… but I just couldn’t think.

Of anything.

As I looked back up at the expectant crowd, not one idea crossed my crowded mind.

I swung away from P.G.’s beckoning hand and bent down towards my wife, Helen, who had read the various drafts.

Helen and Mrs Lennox looked up at my flushed face: “Helen! Helen!” I said quickly … “what is the role of the writer in society?”

Mrs Lennox looked shell-shocked.

But Helen was, as usual, cool.

She smiled up at me and said encouragingly: “Hugh, the role of the writer in society is to make sense of the world.”

That was what I needed … a good start.

So wives can now be called "key stakeholders who mitigate against sub-optimal outcomes". Cool.

When I read "On the evening of May 4 Helen and I dressed in our Sunday best." a feeling of foreboding came over me. I wondered what was going to go wrong, and Hughie, you did not disappoint. I'm glad you rose to the occasion. Or didn't you? (We are left to conjecture)