In 1960, Melbourne teenager Jeff Liversidge – one of six children – failed two of his high school matriculation exams. Unsure what to make of his life in Ferntree Gully, Jeff took a job driving a piano tuner around the Victorian countryside.

But he didn’t like it.

So Jeff bought an old motorbike and headed north to Queensland where he kept moving north until, eventually, he reached New Guinea.

Once on that huge island, Jeff kept travelling north through the jungle and mountains until, in 1961, he reached the longest river in New Guinea up in the northwest corner: the 712-mile-long Sepik River, known as “the River of Crocodiles”.

In a dug-out canoe, he travelled up this winding, twisting, bending, swampy, silent river until he saw something. Something which made him turn his back forevermore on his own known world.

Jeff’s heart had finally found a home.

He settled on the banks of the Sepik for the rest of his life … and never wore shoes again.

I bumped into Jeff Liversidge in what is known as “the Middle Sepik” hundreds of miles upriver from the mouth in October 1978 while on assignment for The Australian.

For a reason I could never fathom, we immediately hit it off: two Australians with stories to tell … me 37 and Jeff 35. I suppose he was pleased to show off his new world to someone from his old world.

I asked Jeff what it was that had caused him to leave behind everyone he knew: his parents, his three sisters and two brothers; everything he was familiar with; and make a life in surely the most remote place on the planet.

The furthest you could get from the suburb of Ferntree Gully.

A man who spoke perfect pidgin English as well as his local village dialect, Mindimbit, Jeff – 17 years later – no longer talked like an Australian.

He spoke softly, almost delicately, mixed in with pidgin habits. Sentences ended with “please” no matter what. Talk was in the future tense: “I will be telling you a story”. Most stories began “Before…” as if that was sufficient acknowledgement of the past.

Very occasionally he would begin “In days gone by…”

He sounded like my grandfather, a timber-getter and bullock driver in the Numinbah Valley behind the Gold Coast. Grandpa Duncan whittled wood with his pen knife to make a child’s cricket bat … or for the relaxation.

Jeff carved crocodile teeth, scraping the enamel with a hacksaw blade to make four-inch-long ear-rings a village husband might buy for a wife who has just given him a baby.

“I will make a hundred. They are fine ivory, and even a big croc has only 6 teeth you can use.”

Just like Grandpa Duncan, Jeff liked telling stories – not about himself, but about the folklore and traditions along the Sepik.

All those years alone in the jungle were carved on Jeff in a hundred different ways. He was not gregarious, he did not tell “jokes”, but had a dry wit you could almost miss. When he did have something to say it was never, ever, about politics or the world outside, but about villages, intricate native carvings, evil spirits, or animals.

He lived without radio, TV, recorded music.

He had never heard of the worldwide hit Jesus Christ Superstar. So I asked if he missed going to the theatre or the movies: “Before… I saw a brilliant piece of theatre here: two cassowaries making love. Very few people have ever seen that.”

If he wanted to attract a cassowary, he would beat the roots of a tree making a hollow drumming sound.

Yet, like an army officer, he shaved every day.

Asked a question, Jeff would think some time before answering.

So, being from the impatient world outside I threw up a few possibilities as to what might have attracted him to make his home on the banks of this unknown river.

Was it the astounding width of the majestic Sepik (a mile wide in some places)? Or the barefoot living as part of nature? Or the 20 distinct tribes dotted along the river, each practising their own unique culture?

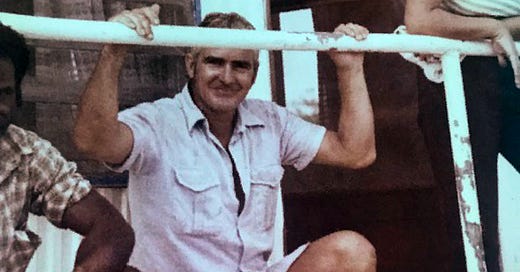

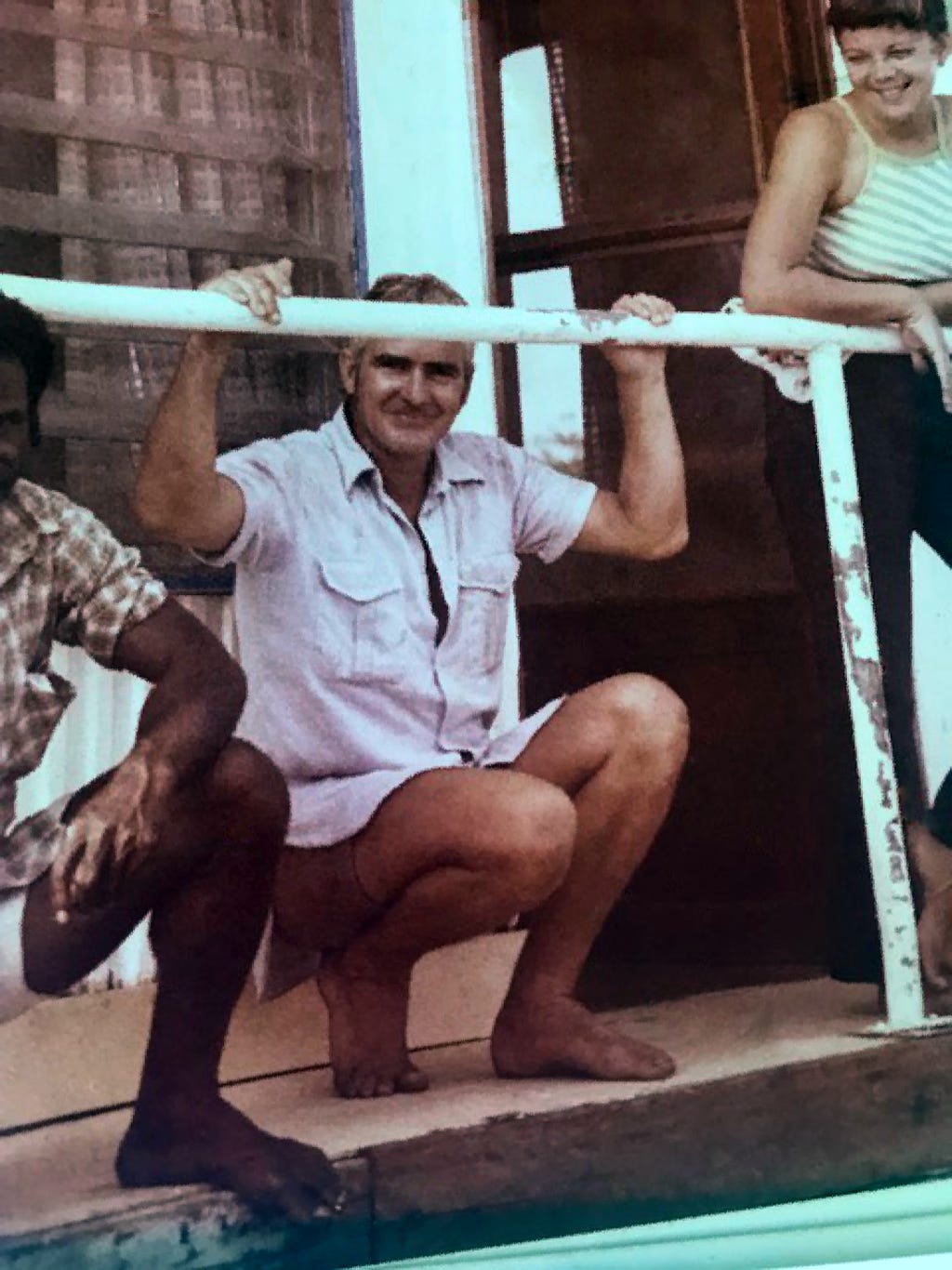

“I will be asking you to listen to a story please,” Jeff answered, while I sat down on a log and eyed his heavily tanned face, his thin moustache, his short fair hair, and his steel blue eyes.

Finally, he looked up as if about to tell a secret, and said something I could not have predicted: “It was the colour of a crocodile’s eye.”

And that was the end of his story.

Never having been close enough to stare a crocodile in the eye I shook my head, not fully believing that this could be his real reason.

“Since before, there is no other thing in nature like it,” Jeff continued. “Maybe you can describe it better than me by comparing it to the neon and flashing lights back in Australia … but I haven’t seen any of those for 17 years.”

Seeing doubt linger, Jeff promised to show me the eye of the crocodile … if I stuck around the muddy riverbanks of the Sepik with him for a few days.

Both of us were to get far more than we expected when that crocodile came.

For his first five years in New Guinea – when it was still legal to kill large crocodiles and so a good living could be made from their skins – Jeff hunted crocodiles up the backwaters of the Sepik and in the Ramu River where few Papuans, and no white men, ever ventured.

His skins were sold at leather auctions in Paris and Italy.

Jeff called a few hundred square miles of the upper Ramu “my land” because no people lived there. “There are crocodiles everywhere though, please,” he added as an afterthought.

Up there, Jeff said, crocodiles had never seen a light. Shooting crocodiles, he was by himself:

“It was in the upper reaches of the Ramu. I shot a 17 foot, he was so big I couldn’t get him out of the water, so I had to skin him in it. I was in a sweat and I thought, $100 yes or no? $100 comes easily to this failed matriculation student and assistant piano tuner.”

Jeff was unable even to estimate how many large crocodiles he killed at that time before it was made illegal to shoot crocs “longer than seven feet”.

This was to ensure their preservation.

Jeff said all the people on the Sepik “are great croc hunters” so they petitioned to have that limit stretched to “more than ten feet” because so many 8, 9, and 10 foot crocs were caught in their fishing nets. These had to be killed … yet they could not then sell the skins.

The petition failed.

“I will be asking you to listen to a story. In days gone by I arrived at a small lake and with my light instantly spotted 50 pairs of crocodile eyes. So there were hundreds in that lake, please.”

Jeff and his Papuan companion axed a quick dugout canoe from a log and set out into the lake with Jeff standing and shooting all the way. But in the middle of the lake the canoe began to sink beneath their weight … and they had to swim for shore.

“Although in water I was sweating all the way. I didn’t like it,” said Jeff.

He might not have liked it, but I was pleased to be in the company of such a brave Aussie man who had the substantial thighs and forearms you would expect in a man used to skinning crocodiles. Because here we were literally surrounded by crocs, and tribes that didn’t look all that friendly, and jungle.

The villagers along the Sepik traditionally were head-hunters and the tribes, being very war-like, stuck to themselves and had little contact with people … except nearby tribes.

The men all constantly chewed betel nut which stained their teeth red. It was so acidic that to neutralize it they needed a constant supply of lime on hand for their mouth. So at their waist, like a dagger in its sheath, they had a thin bone in a container of powered shell.

A man would pull the bone out and draw it across his mouth constantly so that the lime mixed with the betel nut.

Jeff said these tribes had another thing in common: they worshipped the crocodile – no doubt because for hundreds of generations it was the biggest and most powerful constant presence in their lives.

So much so that no boy on the Sepik could become a man until the markings of the crocodile were cut into his body – back and front – in a vicious three-week ceremony.

Jeff explained that, because their world ended within a 50-mile radius of their village, they had developed many legends to explain the existence of mankind.

“Everyone and everything relates to either the sun or the moon, please. There are no accidents in life, as life is directed by many gods. The paramount god of the lake is the crocodile, but it is seen in many forms.”

But villagers looked after one another.

“Before … a girl, 17, was dying of malaria and the whole village was there. Holding her hand. I will never forget it.”

In the village of Ambunti, where Jeff lived, 200 river miles from the sea, a legend “explained why there are men and wives”.

“Before… there was only a spirit. And he said to his wife one night: ‘The lake is full of fish, go and catch some.’ While she was fishing, a human head rolled along and latched on to her breast. The wife called to the spirit: ‘If I pull it off I will die. You will have to help me.’

“The spirit took a mango and threw it 25 yards and the head let go and rolled after the mango and ate it. But immediately it came back to the breast. The spirit threw another mango 100 yards, but the same thing happened.

“The next mango he threw 20 miles into the jungle. The head rolled along and came to a cassowary under a mango tree. It ate some mangoes and latched on under the cassowary.

“The frightened cassowary ran through the jungle and smashed the head against a tree; then it ate the brains. That cassowary later laid two eggs – from one hatched a cassowary and from the other a human baby which was brought up by the cassowary – and that is why the people of Ambunti call themselves The Children of the Cassowary.”

Jeff’s own Sepik love story was somewhat different.

In 1966 Jeff was travelling with a load of giant crocodile skins down from the headwaters of the Sepik several hundred miles to sell them in the only town: Angoram near the mouth.

Exhausted, he tied up at the village of Mindimbit where the houses, made of bamboo and sago leaf, were raised up on stumps surrounded by dug-out canoes, because it is only 20 feet from the swollen Sepik.

A young girl brought him a watermelon, which he ate ravenously.

“So I said: ‘I will be leaving later tonight, I suppose you might like to come?’ And she did,” Jeff told me. But the village was angry, even though, Jeff said, girls on the Sepik were “quite unrestricted in relations with men”.

“It is only as a man’s wife that they are expected to be faithful.”

But villagers followed them for 60 miles.

Most marriages on the Sepik were by a system of exchange of daughters for sons. If an exchange could not be provided then money or goods were required.

Jeff got around this custom in his own way.

His wife’s name meant Gouria Pigeon – a very decorative, large metal-blue bird: the biggest pigeon in the world.

So Jeff captured one of these pigeons and sent it to the village with a message: “I have taken a gouria pigeon, and now I have replaced her with another.”

And this was accepted as marriage.

“When I came back to the village, we were still happily married. So the moral, please: don’t eat watermelon.”

Again I found the story hard to believe. So Jeff took me down river to Mindimbit where he showed me the now tame pigeon waddling around the mud floors of the tiny village on the water’s edge.

It was like a big turkey, a delicate steel blue with a fantailed feathered top.

By the time I met Jeff in 1978 he and his wife of 12 years had five children with one on the way.

Now married into the society, Jeff adopted many of the Sepik ways – including calling in a local glassman for his annual bout of malaria or a bad headache.

The glassman, as Jeff tells it, arrives, talks, and then sits down and starts chewing betel nuts as the villagers gather. He says he can feel something inside Jeff’s head and starts dry vomiting. He eats more betel nuts until the red juice is running down over his body and, on his third bout of retching, an object comes out of his mouth.

He scrapes it clean (it could be a stone, bark, or a bundle of leaves) and says, “You should be feeling better now.”

And Jeff did.

“I can only say there is some definite, positive beneficial effect, please,” he told me. “I believe in it to some degree – in as much as it is always performed publicly in front of the whole village and you are expected to get better!”

That was the good side of the society’s black magic – but there was also a bad side.

The most dreaded person on the Sepik is The Sanguma Man, a specialist in committing the perfect murder: the local hired assassin.

Jeff told of the many methods used.

“He will ambush a person and fill his mouth full of dry leaves and poke them with a stick down the throat so when the body is found there is not a mark on it.

“The Sanguma Men above (upriver from) Ambunti are the worst. They scrape the tiny fine hairs from the leaves of the wild sugar cane into a little tube and blow it into the nose of the victim while he sleeps. He inhales it into his lungs and dies within weeks. The man responsible always claims spirits have done it.”

Another method was to push ultra-thin slivers of bamboo into the body, again leaving no mark.

Black magic was also used as a means of finding things out.

Before … 20 New Guinea kina went missing from Jeff’s house and so he sent word to the older men of the village. One of the men arrived with a piece of bamboo on which was attached a thick piece tied to the end and he held it on the table where the money had been.

“The bamboo began to vibrate in his hand,” Jeff said, “and bounced up and down as he held it, down the stairs, along the track, up a ladder and bashed down the door where a young man hiding in the corner broke down and cried and I got my money. It was a most frightening thing to witness, though I believe they must have known who had it.”

After a murder, a black magic specialist ground up the bones of the dead person and announced he would disappear to a village 50 miles away to kill the person responsible and come back the same way.

“I have not witnessed this. But I do know that the person he names will die,” Jeff said.

One time in a village when Jeff was there, a young man’s wife was killed.

“Three old men met and said they would find out who had done it. One said he would turn himself into a flying fox and fly round the village; another said he would become a dog and go under every house; and the third said he would become invisible and enter every house.

“They named a man as responsible and said his own wife would now die within two weeks. I urged the man to take his wife away but he said it was no use. She did not know of the decision as it was a decision of the men’s house and he did not tell her. But she did die.”

The men’s house, or spirit house, is the one common factor in all the villages on the Sepik. It is a special high huge building of bamboo and sago leaf roof where only men who have been initiated can enter. It might be 12 feet off the ground, making it cooler, hence its other name is house wind.

Here the men sit around burning embers, smoking, and telling tales. They are surrounded by the artefacts of the village: the bamboo flutes which are sacred; the individual carvings that mark that village only; and drums, giant old drums 12 foot long and 3 foot wide, which have been hollowed out by fire – these drums can call any man by his own beat within four miles.

Visitors are generally welcome in Sepik villages if they ever get that far up the Sepik: particularly if they want to buy carvings.

But that is not always so.

One day Jeff tied up our boat on the muddy bank and we walked up the slippery slope into the village of Awatip, the largest village in the upper Sepik.

Jeff particularly wanted me to see Awatip as he said Japanese tourists could not go there because the village had been bombed during the War. Before we went in, Jeff said, “Don’t take any photographs. And no eating.”

I could hear an unusual rasping noise ahead.

We were confronted by a macabre line of old men who emerged from the spirit house. Each had huge holes in their ear lobes and, worse, the rasping noise was coming from them.

They were scraping the bone in-and-out, in-and-out of the lime containers on the waist with thumb and forefinger as if the piece of bone was a dagger.

Jeff said this was a sign the men were very angry and we’d better watch our step.

I then understood why Jeff always had such a gentle hands-behind-back, soft-spoken approach on the Sepik River. And why missionaries had never been successful in Awatip.

Suddenly Jeff said: “Go. Now.” … and he took off for the boat with me in hot pursuit.

We could hear drums as we pulled away. I wrote in capital letters in my notebook: DRUMS ANGRY.

Safely on the water, Jeff said that apparently there was some ceremony going on inside the spirit house that not even the middle-aged men of the village knew about.

“Something sacred to the older men is happening. Their culture is very much intact.”

As we relaxed again on the placid Sepik I reminded Jeff that he hadn’t yet shown me the croc’s eye.

“I will be showing you, please.”

And soon he did.

End of Part 1

Next week: Part 2 The Eye of the Crocodile.

Discussion about this post

No posts

Great story. Thanks Hugh. I'm glad I didn't pursue my adolescent interest in becoming a Patrol Officer. These positions were often advertised in the 1950s.

New Guinea obviously fascinates the adventurous. We do have a family connection with the Leahy Brothers who walked from Buna to Moresby via the Owen Stanley Ranges pre world war 2. Their story has been recorded on film and in books. Your 🐊 story is amazing. Your adventures with the White crocodile man show your courageous spirit, Hugh. The world was a different place then.