Whenever Rupert Murdoch’s News Ltd HQ in Sydney had a difficult “Rupert job” to be done, the executives invariably onpassed it to someone else … definitely not a Sydneysider, no.

Someone expendable … let me see … I know … a Queenslander!

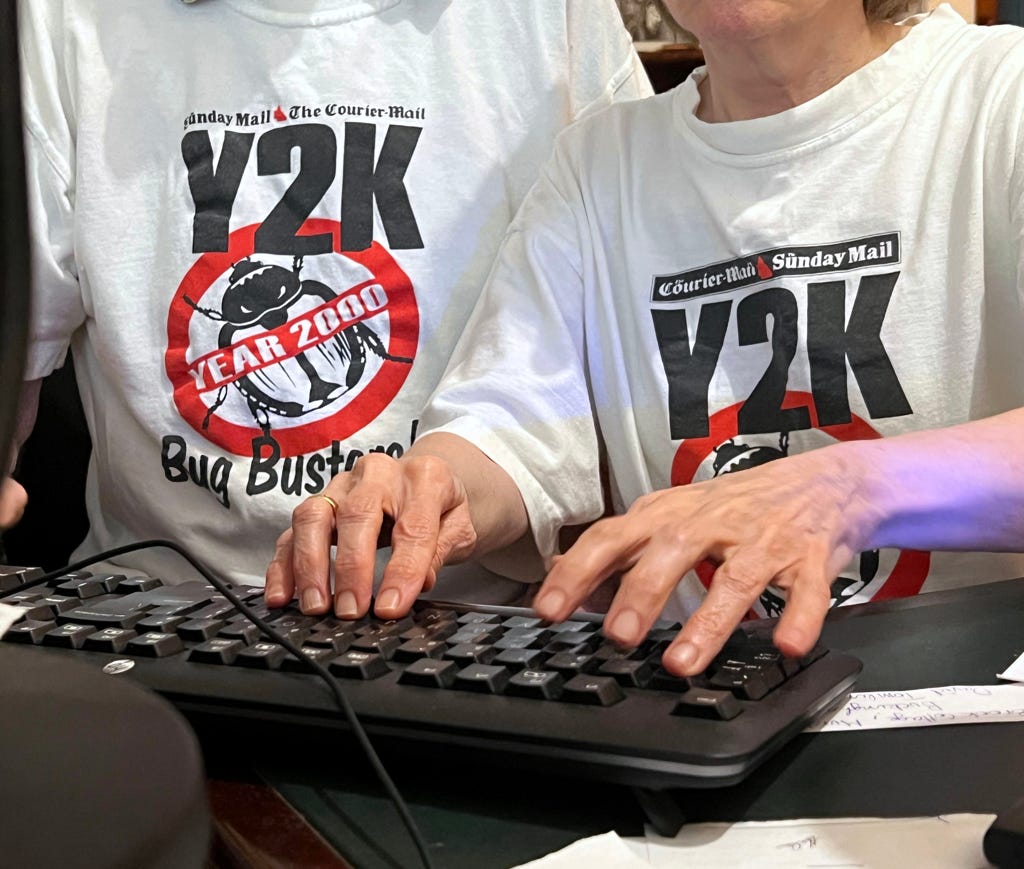

When Y2K was supposed to bring civilization to a halt by confusing every computer on the planet at the turn of the 21st Century, it was my big brother Jack – News Ltd’s then General Manager of Queensland Newspapers – who was given the job of preventing the apocalypse.

Jack put together a team of computer programmers who referred to themselves as “The Y2K Bug Busters!”

Jim Hacker in Yes Prime Minister would have called Jack’s position “the Y2K Supremo”; Sir Humphrey might have called it “the Y2K muggins”.

Luckily for Jack (or could it have been because of Jack?) bugger-all happened.

Had it been otherwise, and the computers that controlled production of all of Rupert’s newspapers, books and magazines collapsed ... Sydney (in my opinion) would have cheerfully blamed Jack who would have been in more trouble than Ned Kelly.

Fifteen years earlier I had found myself in a similar situation.

In August 1985, as a feature writer for The Australian, I was summoned to Sydney to write stories for News Ltd’s Annual Report: a publication dear to Rupert’s heart.

So much so, that it wasn’t a perfunctory financial figures Annual Report like those of other corporations.

Rupert’s report on his vast world media empire, as well as going to all shareholders, was also sent to the President of the United States of America and the Queen of England, no less. Thus, it was printed on high gloss paper and looked more like Rupert’s VOGUE Australia magazine than a business report.

Each year – instead of using one of the army of Rupert photographers in Australia – a photographer was flown out (First Class, mind you) from England to take the pictures. Plus he was allocated a strong young man to carry his equipment and move the silver umbrella, remote lights, and the light diffusers on command.

The designer from Rupert’s London Sunday Times Colour Magazine was also flown out and given separate offices in North Sydney with two assistants.

His job: to make each page of the Report look special.

All of this was so Rupert could, every year, demonstrate for all to see the prestige that came from advertising in his publications, reading his books and magazines, appearing on his TV networks, flying on his airline: the sheer panorama of his power.

In 1985, and then again in 1986, I was dispatched with a UK photographer around Australia to visit each of Rupert’s operations and capture and encapsulate his dynamic company in action.

This was by no means an easy task because Rupert owned newspapers, magazines, book publishers, TV stations, a huge sheep station, an upmarket Great Barrier Reef tourist resort … assets splashed all around the country. Like the Northern Territory News in Darwin: a place so far from everything else that Australians call it merely “the Top End”.

Time was of the essence as Rupert’s Annual Report had to be in the hands of various Stock Exchanges around the world by September 30.

On the 1986 expedition there was a completely unexpected hiccup which could have cost me a vital couple of days.

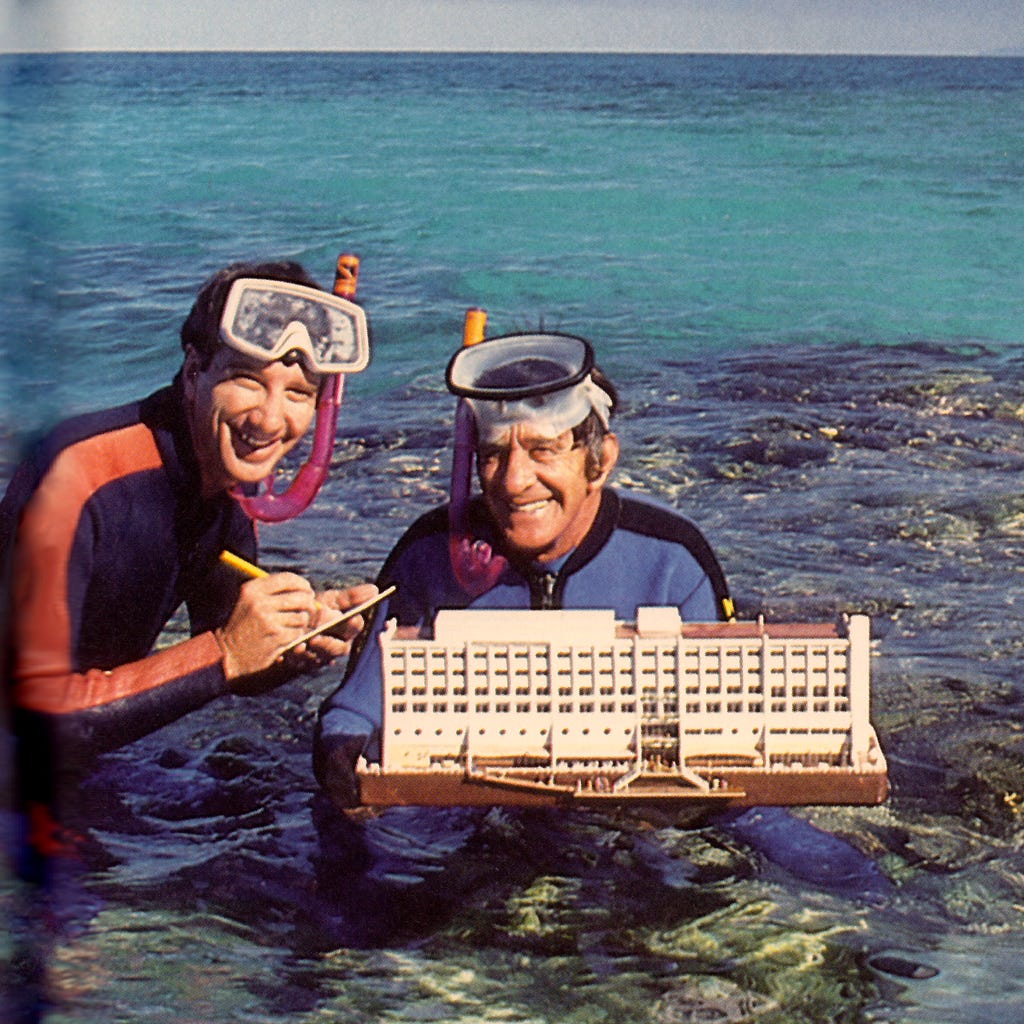

I had to get the 1,600 miles from the Darwin Races to Townsville (where Rupert had recently acquired the Townsville Bulletin) to write about that newspaper and a proposed new “floating hotel” on the Great Barrier Reef: with pictures.

But there were no direct domestic flights between those two cities.

I would have to drive east for two days … or else backtrack 3,500 miles by air south to Adelaide; across to Sydney; and thence up through Brisbane and on up to Townsville. (Australia is a much bigger country than anyone in Sydney ever imagines.)

Qantas 747s flew direct from Darwin to Townsville on their way to Hawaii, but – because Qantas was our overseas carrier – they were not allowed to carry domestic passengers in opposition to the two domestic carriers: Rupert’s Ansett and the government-run TAA.

Thus Qantas flew that 1,600-mile leg largely empty … except for the rare individual wanting to fly from Darwin to Honolulu.

So I came up with a cunning plan.

I would buy a Qantas ticket from Darwin to Honolulu at Rupert’s expense, but get off and disappear when the plane stopped to re-fuel in Townsville.

But to pull off this rort I needed a new passport.

In a hurry.

I dashed into the passport office in Adelaide Street, Brisbane, with only hours left. While impatiently waiting in the queue, a bloke came out of the main office towards me: “Hugh! Hugh! Hughie! How’re you going? Nice to see you again.”

I was thinking Who the hell is this? I’d never seen this gentleman before in my life.

“What a marvellous dinner that was, Hughie. And how is Jack? Lyn is an excellent cook, isn’t she? And so quick with that sharp wit of hers! Oh, yes, wasn’t that a great evening, I think I drank a bit too much. You never want for anything at their place.”

At the counter, they told me I needed six portrait photographs for one passport – there was a photoshop downstairs.

I ran back up the stairs with the six pictures only to learn that each photo was invalid unless it had been signed on the back by a person who could vouch that I was actually me … if you see what I mean.

Desperate, I poked my head into my new friend’s office – the man I didn’t know – and explained the dilemma. He regretted that, although he was in charge, there was just no way around this iron-clad Canberra rule: each photo would have to be signed on the back by someone who knew me.

“Then you can sign the pictures!” I said, knowing there was only an hour to go.

No, he didn’t think he could do that.

It wouldn’t be right.

“But you know it’s me! You told all those funny stories when we had dinner together at Jack and Lyn’s place.”

Reluctantly he signed and I took a quick peek at the six signatures and exclaimed: “Thanks Roger! You’re a champ!”

I was on my way.

The theme for the 1986 Annual Report was “A Day in the Life of The News Corporation”.

At Rupert’s Progress Press in Melbourne there was more happening than anyone could imagine. The place was churning out four million full-colour catalogues for K-Mart, to be distributed to four out of five Australian homes within the next 48 hours.

I was told it was not to be called junk-mail, they were “brochures”.

The previous year Progress Press had put 865 million full-colour items through Australian letter boxes. Plus it was printing millions of magazines a week. The two apartment-block-sized presses only stopped Christmas Day – and that was for maintenance.

Finally I understood Karl Marx’s phrase “the means of production”.

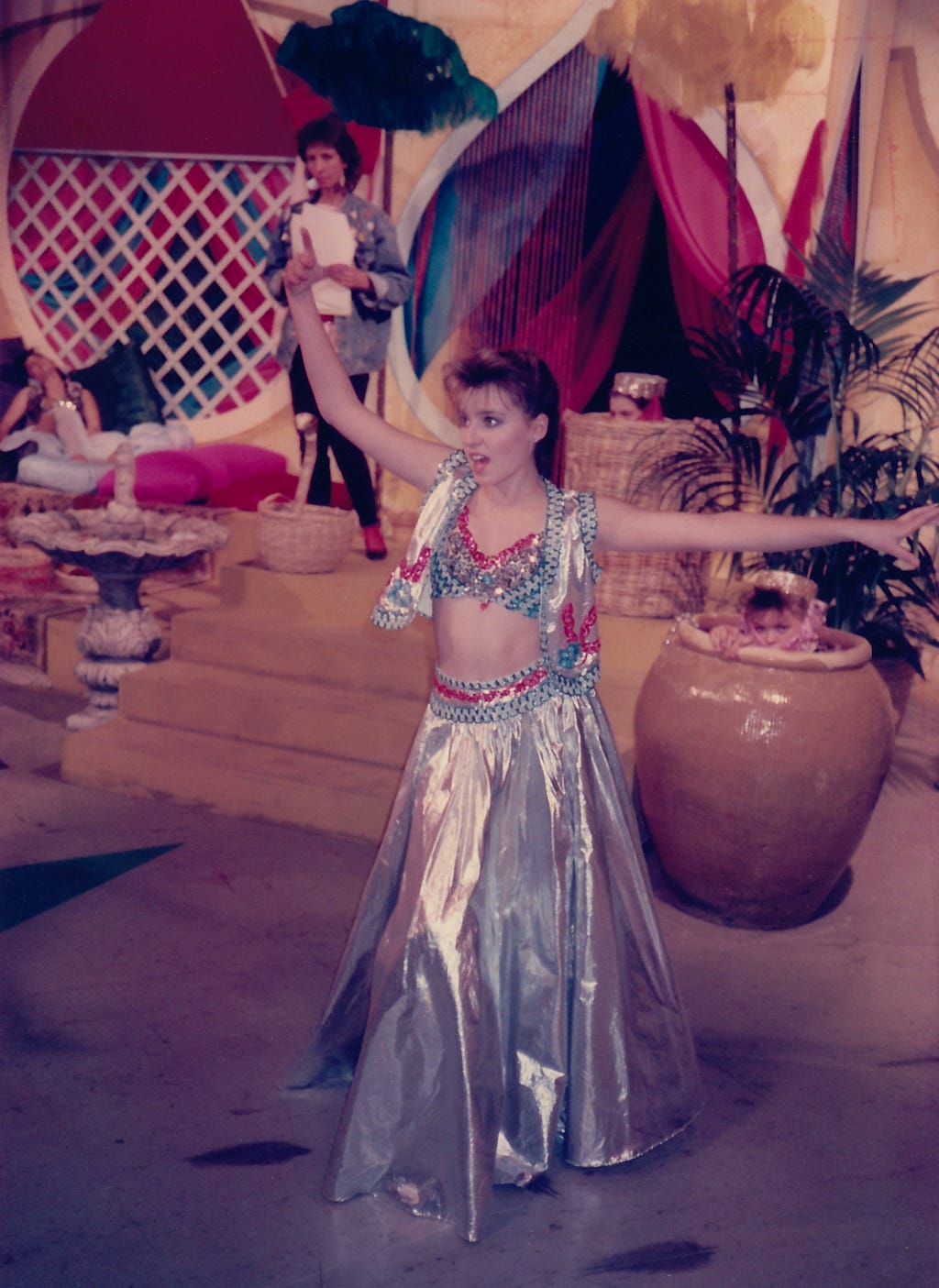

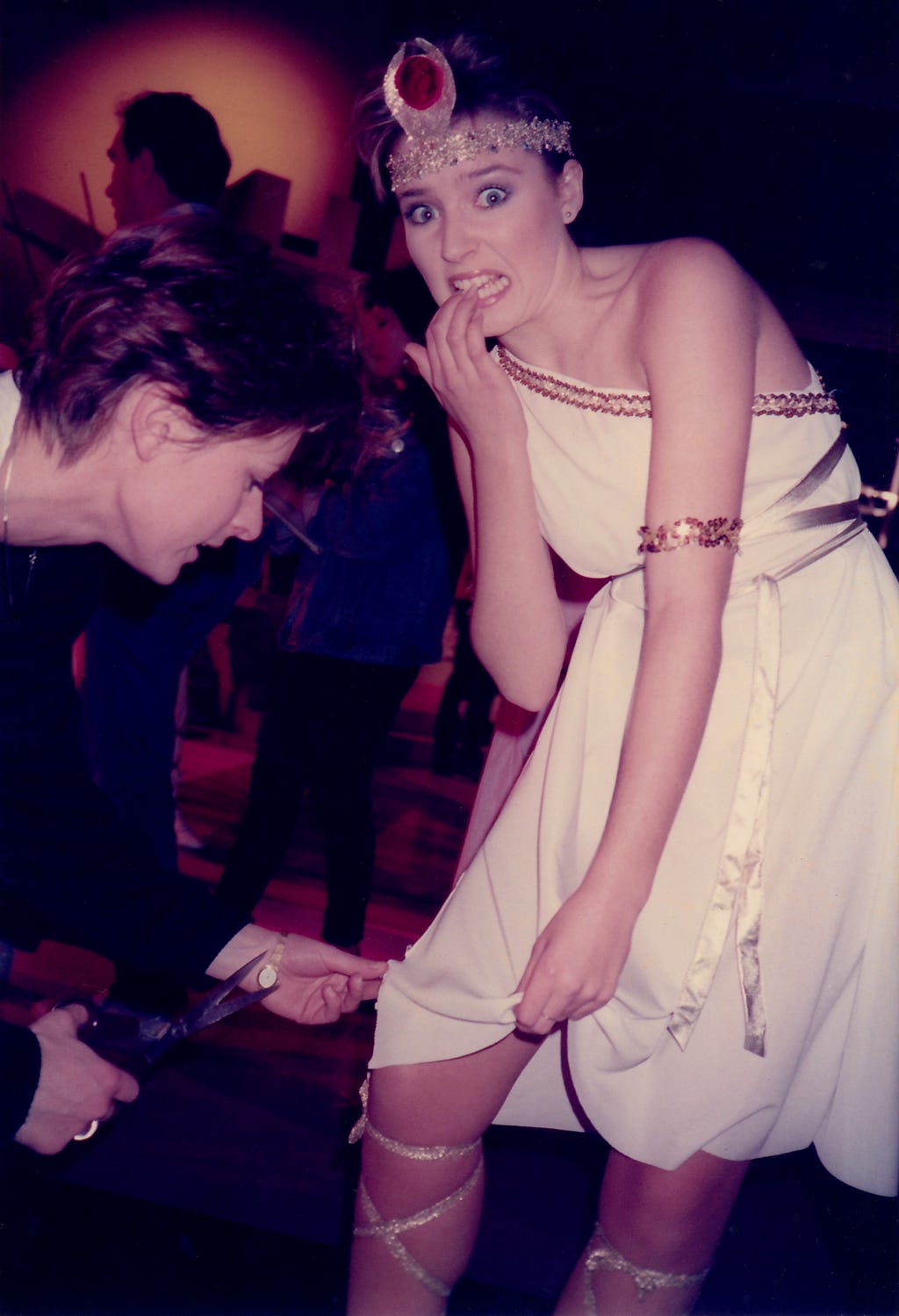

That afternoon I went to Rupert’s Channel 10 to watch the taping of his top-rating TV show Young Talent Time which starred 14-year-old Dannii Minogue, younger sister of the then unknown Kylie.

I was amazed how these young performers warmed up for an hour: like Olympic athletes.

I’d also written about Channel Ten in Melbourne the previous year, 1985, but that time to illustrate how well Rupert’s network worked for advertisers.

This involved interviewing a furniture manufacturer (do we still have those?) who spent more than half a million dollars a year advertising on Channel 10 “to let the shoppers come to me”. He said it was important that his TV ads annoyed people: “That’s what makes them memorable. The more my ads irritate people, the more furniture I sell!’’

Next stop a businessman who loved flying on Rupert’s (half-owned) Ansett Airlines; then a boutique owner who was attracted to Rupert’s New Idea Magazine which sold about a million a week “because of the variety of articles”; then a woman executive who loved Rupert’s TV Week because it saved her changing channels.

In Sydney I was sent to NSW Sports Minister Michael Cleary who happily posed while holding Rupert’s Sydney Mirror; Edmund Capon, director of the NSW Art Gallery, waxed lyrical about why he read The Australian; and others on why they read Rupert’s Sydney Daily Telegraph.

I was seeing Rupert-power in action.

I even drove down to the Georges River to interview a housewife, Betty Stubbings, who taught cooking after reading a publication of Rupert’s Bay Books: Microwave Cooking Made Easy.

In the midst of all this mayhem, the Editor of The Australian, Les Hollings, had been ringing everywhere trying to find me (no mobile phones in 1985). Rupert’s wife Anna Murdoch (née Torv), a former journalist, was in Australia to promote her first book, a novel titled In Her Own Image.

As a Queenslander I had been especially chosen for the job of interviewing the boss’s wife.

Thanks a lot.

Rupert was in the US in August 1985 about to be naturalised (on September 4) as an American citizen to satisfy the legal requirement that only U.S. citizens are permitted to own American TV stations. Meanwhile, on the shores of Sydney Harbour at Elizabeth Bay, I was inside his home taking tea with his wife.

There was a huge, wide, tree-and-lawn garden in front of the brick block of apartments which had unspectacular partial Harbour views. I was surprised that inside it wasn’t more luxurious.

Over several cups of coffee, Anna and I discussed In Her Own Image.

I was able to carry on a detailed conversation about the characters because, unlike most reviewers, I had read the book from start to finish: which, I knew from having published four books myself, was a rare compliment to an author. I didn’t have to ask the usual: How long did you take to write this book?

And, as much as I dared, I asked about her husband of 19 years.

Anna told me that she would become so focused on her writing that she often hadn’t cooked dinner by the time Rupert arrived home. “I learned to put a pot of boiling water on the stove so it appeared something was happening. It always worked.”

What did Rupert think of his wife, the mother of their three children, becoming an author?

“Rupert was a big help once he accepted that this was what was going to happen,” Anna said. “Once he saw it was going to come off, he was my greatest support.”

She said Rupert took over the role of mother: at one stage taking Lachlan, 13, and James, 12, for a holiday in the Colorado snow while Anna slaved to finish her novel. He also did the cooking!

Was he any good as a cook?

“The thing is that Rupert has great confidence in whatever he does,” Anna said. “He may not know how, but he attacks the task with great enthusiasm and confidence, and so fools everybody into thinking he can do it.”

And what about the athletic, romantic, truculent hero, Harry, who dominates the novel and owns what is very clearly Rupert Murdoch’s grazing property? What did Rupert think of this Harry – the bloke who is so sexy that both sisters fall in love with him?

“Rupert read the manuscript in Rome when we were staying there at the American Embassy,” Anna said, with a revealing nostalgic air.

“When he finished the book, he put it down next to him, looked up at me, and said, `Who the Hell’s this Harry guy?’

“I said, ‘It’s all based on you darling!’”

Anna added that the book was, of course, fiction.

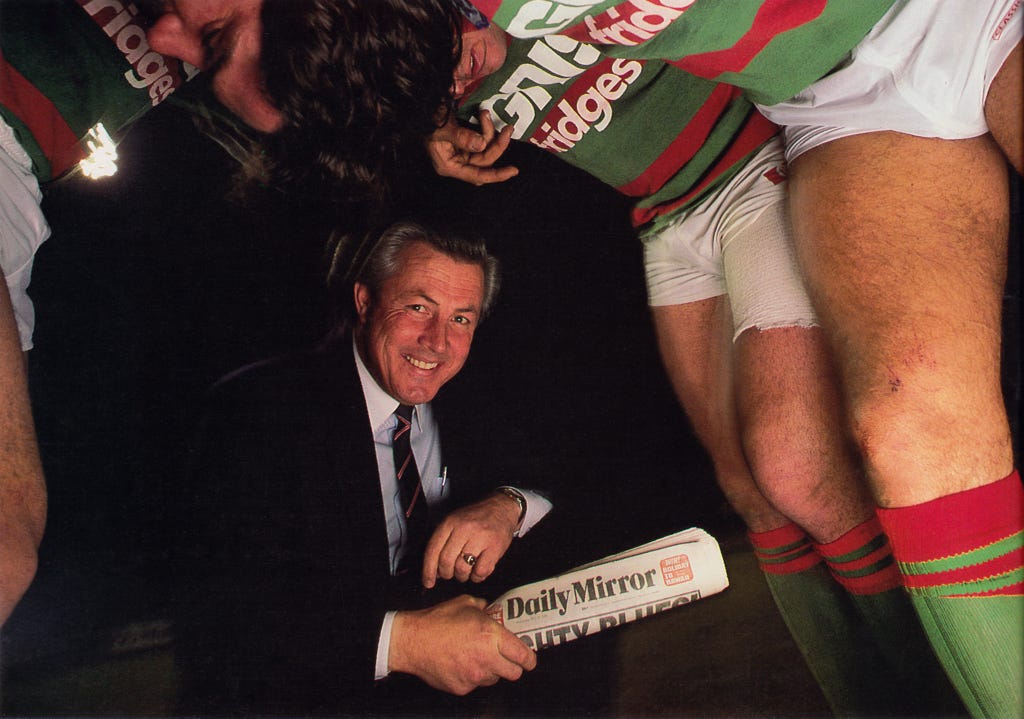

There was no time for me to write the In Her Own Image story in Sydney that evening because I had to go straight to a Souths rugby league training session for a picture story for the Annual Report.

Next night, in my room in the Melbourne Hilton, I bashed out the Anna story on my portable typewriter.

Then, on the way to Adelaide to interview Jeremy Cordeaux – who said his top-rating radio program would be “impossible to put to air” without Rupert’s daily paper The News – I took my 3,000 words on Anna to Rupert’s Melbourne Southdown Press Building, running up the hill in Latrobe Street.

I personally handed it over to be telexed to Sydney for publication that weekend.

My opening line was about Rupert Murdoch saying suspiciously to his wife “who the Hell’s this Harry guy?” … because it was a unique insight into the covetous mind of the world’s biggest media proprietor: Australia’s most famous man.

So I had the exclusive inside story.

Next morning at the airport I picked up a copy of the opposition Fairfax AGE Melbourne newspaper (two days before my story was to be published in Saturday’s Australian). The first thing I saw was “Rupert asks wife Anna: Who the Hell’s this Harry guy?”

I’d been scooped by my own story.

What I wanted to know was: Who the Hell had leaked the start of my story to the Fairfax opposition?

Rupert was right to be suspicious … of everyone.

I never found out Chris, but it could have been anyone form the telex operator to a journalist with a good friend on The Age.

Please note Frank Palmos's comment: that Rupert did it!

Well done Hugh, obviously one of the most challenging tasks for a News Corporation journalist was to contribute to Rupert's Annual Report. Great initiative getting your passport ready in such short time for the international flight from Darwin to Honolulu, and then getting off in Townsville!

Loved reading about Anna Murdoch putting on a pot of boiling water on the stove so it looked like something was happening if Rupert arrived and dinner hadn't yet been cooked.