Every year at this time – when Dragons take to the streets and red firecrackers explode – there is a group of us whose thoughts turn to a different Chinese New Year.

1968: not so festive … but louder.

It wasn’t the Year of the Snake like now, it was the Year of the Monkey. I’d been in Vietnam for 12 months and had only four days and a wake-up to go.

I’d survived!

Every correspondent who lasted the first 11 months (without getting killed or seriously wounded) was allowed to spend the last month safely ensconsed in Saigon … instead of putting on an American military uniform and heading out into “the field”.

The field was anywhere outside Saigon, and it was all dangerous – places like Dak To, Con Thien, Loc Ninh, Gio Linh, Dong Ha, Ban Me Thuot, the Hiep Duc Valley, the Mekong Delta.

Perhaps because China ruled Vietnam for 900 years, the Vietnamese also mark the Lunar New Year. But they call it “Tet” … and, just as in China, this celebration is like Easter, Christmas, and your birthday all rolled up into one.

Truckloads of flowers in pots poured into Saigon and were laid out to cover whole roads with a sea of colour and everyone was, for once, happy and relaxed because there was the annual Truce for Tet.

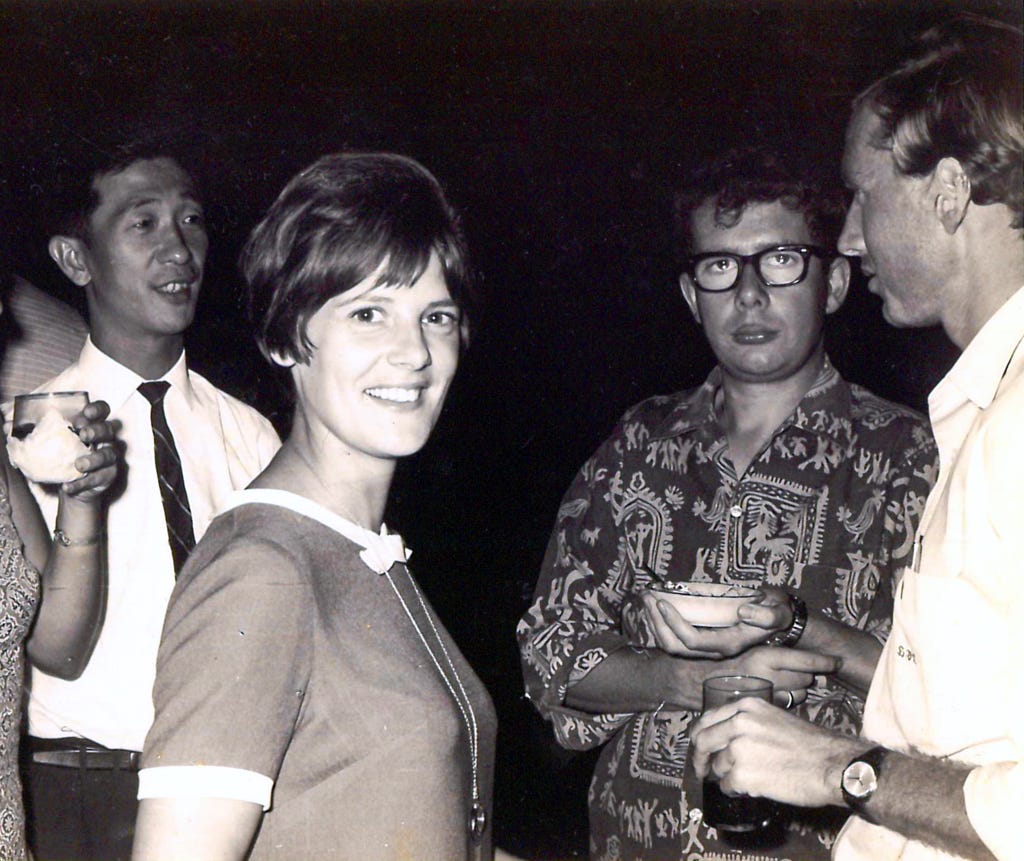

My girlfriend, Julie Beard — a girl who both wore a mini and drove a Mini — and I strolled hand-in-hand through the flowers and the busy market stalls.

Peace at last.

My Bureau Chief and close friend, Jim Pringle — who was usually bent over a typewriter working — took photos of us. Even Jim, a dour Scot, was in holiday mood.

Then something odd happened.

We were walking three abreast through the market crowds when a darkly tanned rugged-looking Vietnamese man seemed to deliberately bang into me front-on with some force. I automatically turned around to apologise, and he gave me the worst look of hatred I have ever seen.

Jim and Julie witnessed this, and we were all at a loss because everyone else in Saigon was celebrating Tet.

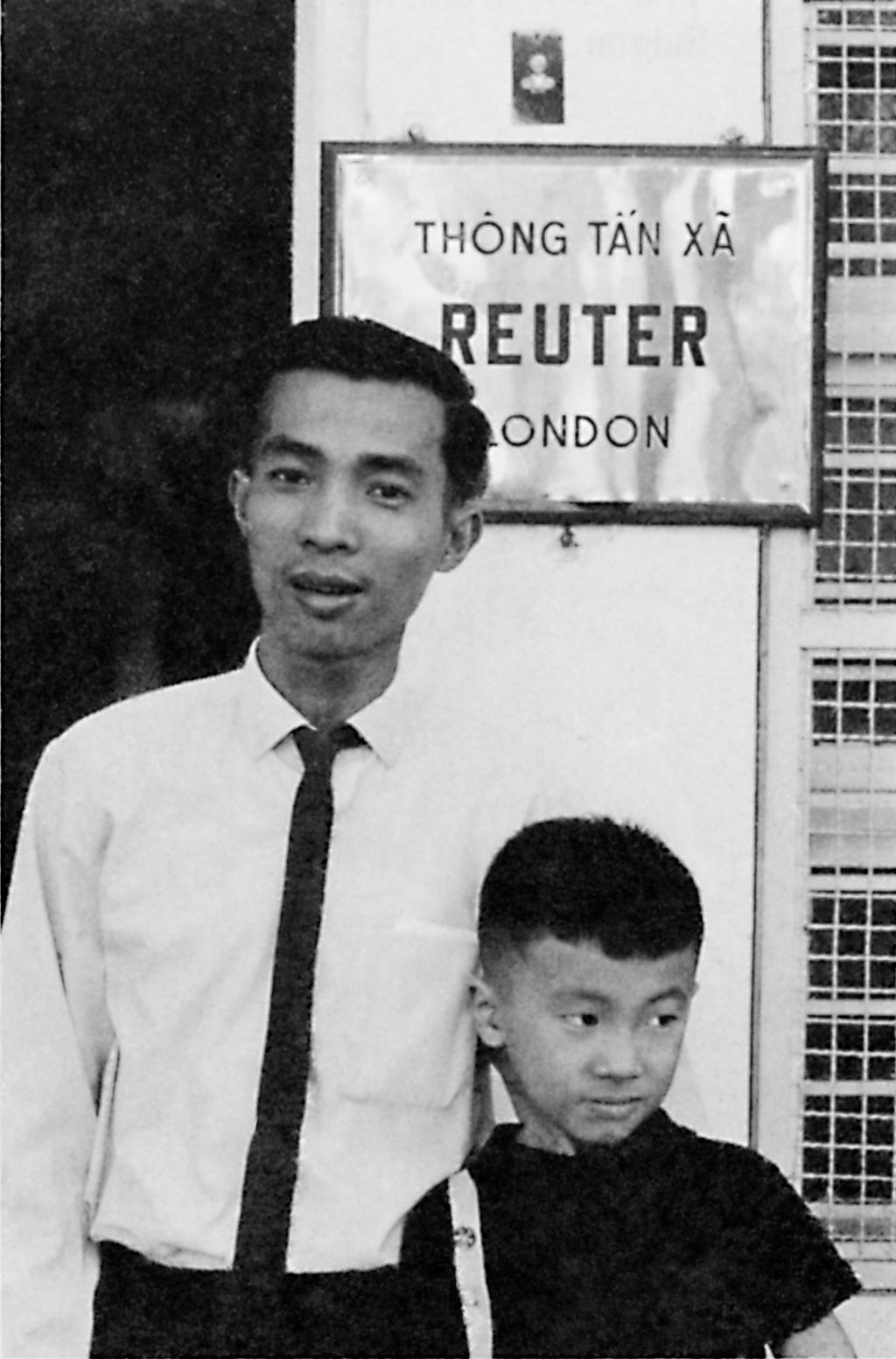

That evening in Reuters office at 15 Han Thuyen Street I was sitting at my desk typing a Truce update story while our Vietnamese reporter, my good friend Dinh, was speaking at the entrance to another Vietnamese man.

They were both holding on to the open white steel-mesh grenade door with their fingers through the wire while looking out to the treed park opposite … trying to keep cool.

I was hurrying to send off my “nightlead” story because Julie was standing in the office by my desk waiting for me to finish so we could go home to her place for dinner.

Eventually, Dinh came back in and sat at his desk opposite mine: staring at his hands for several minutes.

Suddenly Dinh leapt up. Determinedly took three paces across the room. Ignored Julie. He leant across my typewriter and said: “Gunsmoke, you tell Miss Julie go home!”

Surprised, I said: “Hey Dinh, when did you start running my social life?”

“She go home! Tonight the VC attack Saigon,” Dinh blurted out, as if this were the only way to tell me such immense news.

Miss Julie scoffed: “Huh! What? That’s ridiculous! … Hugh, do you want to come to my place for dinner or not? It is a holiday you know!”

Julie was a secretary at the British Embassy and lived in their compound less than two miles away. I was looking forward to eating something that wasn’t combat rations.

Dinh insisted he was right: “VC already in town … come on trucks … behind flowers!”

I said if that were true then I should put it in my “nightlead” – a summary of the day’s events for Reuter clients around the globe.

“Hugh,” said Julie interrupting, “we’re in the middle of a bloomin’ Truce! If that’s right we would have heard about it at work. We’re in constant contact with the Americans and the British Embassy would be the first to be told. We’ve got our own intelligence people too you know! Reporters don’t know everything.”

It was true that the communist guerrillas had never got within cooee of Saigon – even under the French — and now there were more than half a million US soldiers in Vietnam.

There’d never been so many.

“Julie I understand what you’re saying,” I said, “but I have to trust Dinh. If he’s right, then I have to be here when it happens. It would be the biggest story in the world since JFK’s assassination!”

Miffed, Julie stomped off in her high heels across the tiled floor … past Dinh … past the shelves of files in ring-binders … past the open grenade door … and jumped in her little white Mini Minor and sped off to the British compound without saying goodbye.

I was caught between my job and my new romance.

So to be doubly sure, I did something I’d never done before: I queried the ever-reliable Dinh about his source for this information: “If that’s true Dinh, then it should be in this story I’m writing,” ... and I made as if to type what he’d told me.

We had become close mates over the last year, so I knew Dinh was deadly serious when he said fiercely, holding up his right hand as a stop sign: “No source! No background! No report! But must be ready. First with big story!”

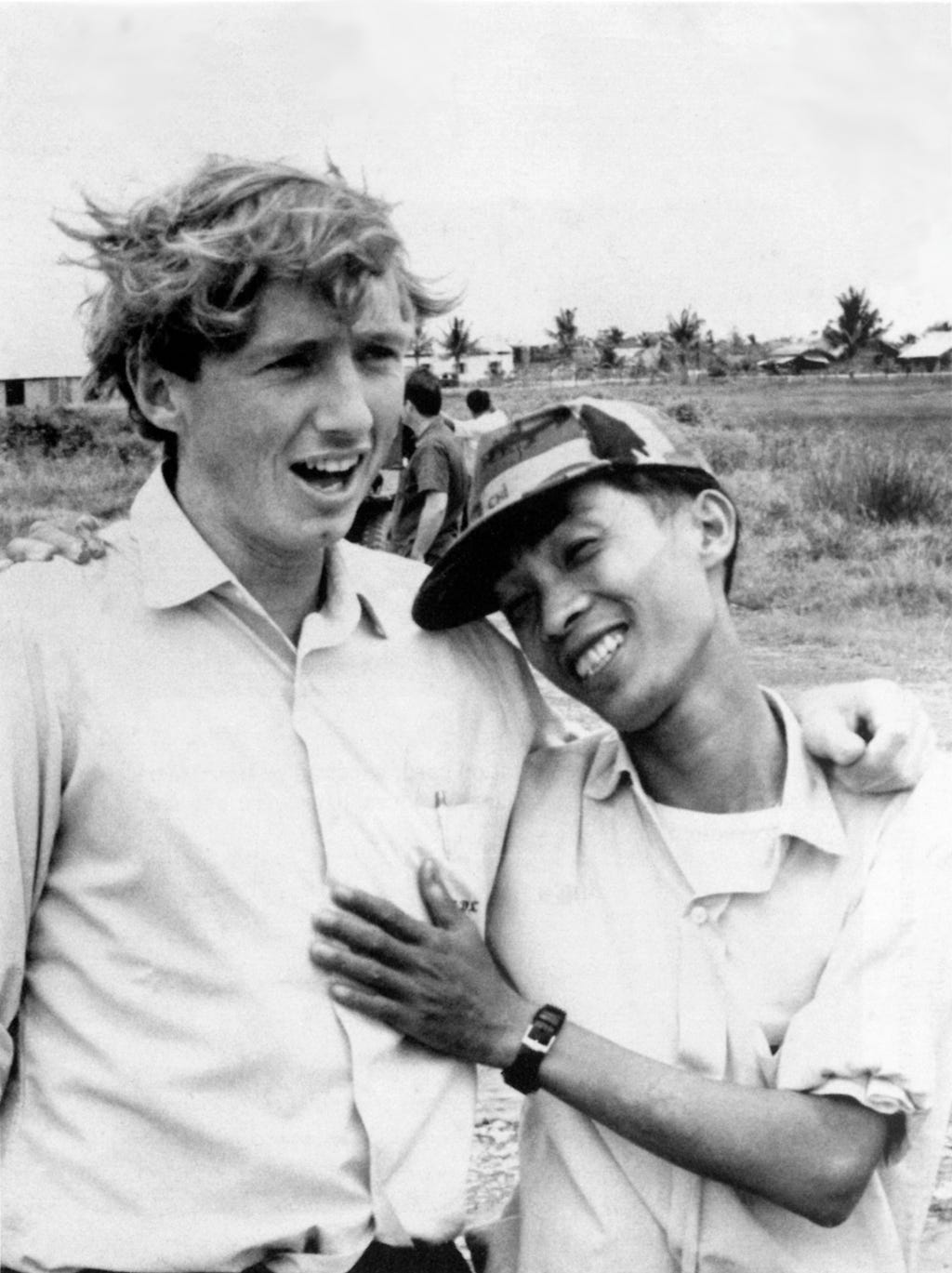

Jim Pringle — veteran of so many wars that Reuters said they wouldn’t bring him back to London in case war broke out — lived above the office to be ready for anything.

I called him down.

On hearing the news Jim stood silent, staring straight ahead through his Coke-bottle-thick glasses, those pugnacious pink lips pursed. One fist leaning on his desk.

I could hear him thinking.

Eventually, Pringle made his judgment. There had been no whisper of this from anyone else — we were in the middle of a Truce. But we were obliged to act as if Dinh were right. To do otherwise would be foolhardy.

Dinh said they would attack at 1 a.m., so Jim told Dinh to go home to his family and come back at midnight.

With a few hours to kill, so to speak, Jim Pringle and I walked a couple of streets to the New York Times office to tell them the news – hardly believing it ourselves. Journalist Tom Buckley got beers out of their fridge – he said we needed a drink to calm down.

After midnight we walked back to the office even though it was after Saigon’s shotgun curfew.

As we strolled alone in the hushed dark — silent enough to hear a bullet drop — I knew Dinh was wrong. If something were going to happen surely the Americans, with 10,000 intelligence people in Vietnam, would know? They kept saying the tiny base of Khe Sanh up north next to the North Vietnam and Laotian borders was under threat. Surely they would know if Saigon was?

Back at the office Pringle rang Dinh and suggested that, as nothing was happening, maybe he should wait.

When Dinh agreed, our last nagging doubts disappeared.

About 2 a.m., with Saigon deathly quiet, Pringle dropped me off at Julie’s British compound: I pushed open the high flat-steel spike-topped gates and walked in, unfortunately leaving them ajar.

When I reached the flat Julie shared with her younger Embassy colleague Norma, she was asleep.

Since I’d worked for the last 20 hours I took a shower: Julie might get up and I could apologise for our misunderstanding. Suddenly, as I came out of the shower into the bedroom, there was gunfire outside. Explosions shook the building. A claymore mine blew up the Philippine Ambassador’s house next door. Fin-and-spin stabilised six-foot long rockets started exploding nearby.

Julie rolled over, looked up at me, and said matter-of-factly: “It’s started, hasn’t it?”

I rushed out on the balcony and watched guerrillas emerging from manholes outside the steel gates that I’d left open. They fired on the US Transport Depot opposite, and the American soldiers guarding it replied with a hail of bullets. I hoped the VC wouldn’t retreat into our compound.

Norma appeared from her room. Crying.

I had to get back to Pringle and the office: Saigon was under attack.

But no chance: I then realised we weren’t even safe in this flat. I checked the front door was locked. Locked the bedroom door. Ushered the two girls into the bathroom and locked that door too. Three flimsy plywood doors between us and the ferocious attacking Viet Cong.

I wouldn’t have been surprised if an armed guerrilla turned up in the bathroom to join us.

We three sat on the tiled bathroom floor — protected by the bath on one side and the toilet on the other — and listened to the fighting and exploding rockets which didn’t cease for a moment.

Norma said plaintively: “I don’t mind the gunfire so much; it’s the rockets.” I didn’t tell her that the rockets meant guerrillas six miles away, but gunfire was from right outside.

Norma was upset but Julie was angry.

With her elbow on the toilet seat, she asked: why didn’t her Embassy know what Dinh knew? What was wrong with the Americans? Didn’t they know what was going on? They were always so confident they were winning the War.

At first light of dawn, I jumped in Julie’s Mini and drove along completely deserted roads expecting to meet a band of armed guerrillas at every turn. But I didn’t fear them as much as meeting Jim Pringle … after I’d left him alone to cover the first invasion of Saigon without me.

“It’s been terrible Hugh,” were Pringle’s first words as I appeared through the now closed grenade door … and, for the first time, I fully realised just what was upon us.

Pringle, who had covered many wars was tired, exhilarated, and, if it were possible, scared.

Bullets had been bouncing off the footpath outside. There was a bullet-hole through the little brass Reuters sign on the front. Our Vietnamese telex operator wouldn’t come out from under the stairs, so Jim had telexed his own stories. Neither of us knew then that the telex operator was VC. But he did light shaky matches so that Jim could write out his despatches with a pen on the floor.

After years of Washington saying they were getting closer and closer to winning the war – “he’s hurting” “the light is at the end of the tunnel” “we’re over the hump” “we’re rounding the corner” – suddenly the Viet Cong were, for the first time ever, fighting throughout the very centre of Saigon.

They’d even broken into the fortress that was the American Embassy, a street from our office.

Thus Pringle told me to rush to the Embassy and report the battle.

Relieved to finally be helping Jim, I ran to open the grenade door but returned to reality when he called out from his desk: “Hugh! Watch out for the sniper across the road, aye.”

I felt forgiven.

As I cut through the park opposite to get to the US Embassy side of the road I could have been off for a stroll in my rolled-up shirtsleeves on a warm post-dawn morning under a clear blue sky… except for explosions and gunfire.

When I rounded the red brick Notre Dame Catholic Cathedral dominating Saigon’s main street I viewed the wide road outside the Embassy.

It looked like a movie set.

A 1950s black Citroen was riddled with long rows of bullet holes running along the side. Not far away was an American Military Police (MP) jeep, its windscreen shattered by bullets. Opposite the Embassy, behind every tree, American troops in flak jackets, some still in their pyjamas, lay prone as they aimed their M-16s and fired at their own Embassy.

Except for the sniper, who was in a partially-constructed building away to the right, the Embassy side of the road was the safest place to be. I crept past MPs reloading rifles from tins of bullets.

Two of them lay dead face-down on the road. The VC had surprised them by arriving in civilian sedans.

The American Embassy building was surrounded by a high reinforced-concrete wall; 24-hour Vietnamese guard boxes outside; huge flat-steel spiked gates; and US Marine guards inside. The entire six-storey building was covered in a chalk-white grill-patterned protective masonry façade.

The sort we call breeze-blocks.

The Americans called this building “Pentagon East”.

Yet a hole had been blown in this wall during the night and 19 guerrillas in black pyjamas attacked … and 19 were inside. The tall thick timber Embassy doors had been blown apart; the round emblematic Seal of the Embassy at the entrance had been shot up and lay on the foyer floor with other rubbish.

As I reached the driveway entrance to the Embassy – whose steel gates were now open — the street went quiet as if the movie projectionist had turned off the sound.

Against my wall adjacent to the shot-up Citroen, a cluster of American soldiers peeped around the corner into the driveway, rifles raised from the elbow showing it was safety catches off. One of them was surprised to see me. “Get out of this area,” he ordered, “there are VC everywhere! And snipers! And mines!”

Gunfire got everyone’s attention.

One of our group – the biggest of them – picked up an M-60 30-calibre machine-gun (something I would not have been able to lift) with its belt of ammunition dragging on the footpath and, firing from the hip, dashed through the gates saying “I’m going in to get those motherfuckers”.

He didn’t make it far because I could still see his boots on the ground. Other US soldiers shot their way in to drag his body back out and he lay dead next to me on the pavement — his war now over — while gunfire went on around us to no apparent avail.

The US Embassy was too well fortified to be readily re-taken.

I rushed back to the office to send a story to London: the Viet Cong were fighting the war on American soil for the first time. The communist guerrillas controlled the first five floors of the Embassy building. Three US Marine guards, two of whom were wounded, were still holding the top floor.

And it wasn’t even breakfast time.

By now Dinh had reached the office on his motor-scooter – a hazardous thing for a Vietnamese civilian to do – and he returned to Pentagon East with me.

As we crept along the wall something completely unexpected happened.

A hyped-up US soldier swung his M-16 down and around with his finger on the trigger and pointed it directly at Dinh next to me shouting “OK Charlie”. I thought he was going to shoot Dinh but, even so, I was speechless.

The quick-thinking Dinh raised his hands above his head and said: “Not Viet Cong. I number one anti-communist!”

With a perplexed look on his face the American soldier returned to the battle. But, as Dinh later remarked: “How he really know? Cannot!”

As we reached the Embassy, four American soldiers were bringing out a captured guerrilla with a darkly tanned face. Each pointed his rifle into the man’s back. As he walked past Dinh and me, hands in the air, his look of defiance contrasted with the contorted looks on the faces of the fighting four as an officer yelled at them repeatedly: “Don’t shoot!” “Don’t shoot!” “Don’t shoot!”

As more and more Americans shot their way into the Embassy grounds, a helicopter finally managed to land reinforcements on the rooftop helipad and, with the wounded Marines, they fought their way back down through the building.

After sending more stories, Dinh and I once again ventured back to the Embassy: the 19 Viet Cong in the suicide squad had been killed or captured. Dinh pointed at two of their bodies and remarked that they wore white shirts beneath their black clothes, and jewellery.

“Not Viet Cong peasant. Saigon underground man. Show way,” Dinh told me.

That Wednesday morning of the Truce, in almost all cities and towns in South Vietnam, battles were being fought as part of the panoramic Communist Tet Offensive of 1968. Elsewhere in Saigon the VC were fighting in a factory, in a graveyard, in an uncompleted central city building, in the Chinese quarter of Cholon, even on the racetrack.

But none of that mattered.

It was the capturing of Pentagon East that gained the attention of the world.

At that moment, on that morning 57 years ago when I was 26 years old, the people of America stopped believing their politicians. They now knew the USA – the most powerful country in the world – was losing a war for the first time.

In a matter of weeks the US military commander for the last four years, General Westmoreland, was withdrawn; followed quickly by President Johnson’s announcement that he would not seek nomination for a second term as US President.

After the Vietnam War crawled to its inevitable close when North Vietnamese tanks captured Saigon’s Presidential Palace 100 yards from the Reuters office in April 1975, a better reporter than me wrote:

“The Tet Offensive of 1968 stood at the very epicentre of US experience in Indo China. Before Tet all was build-up and optimism. After Tet, all was withdrawal and recrimination.”

My night hiding on the bathroom floor with those two lovely British girls – Julie and Norma – is my strongest memory of that Chinese New Year. The Tet Offensive was officially listed by world newsagencies as the biggest story of 1968. Even bigger than that year’s assassination of Robert Kennedy.

(You can read the full story in my book Vietnam: A Reporter’s War which is still in print today with HarperCollins)

Again Hugh, superbly written and holds the reader alert - even to the horrific circumstances that many went through and are still going through today.

Deserves to be read and reread. Gay

Almost forgotten history and so well told