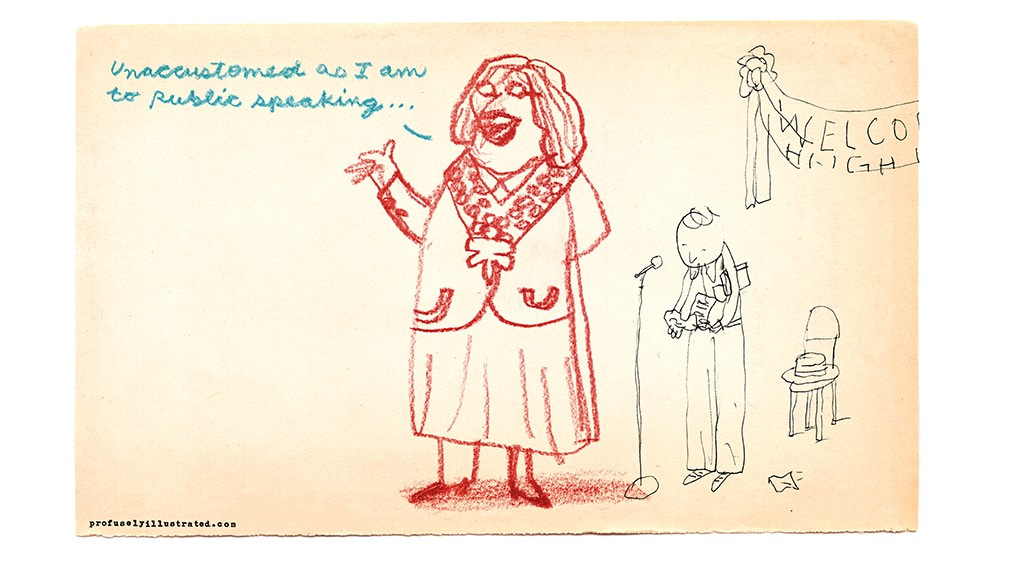

When you’re the guest speaker, no matter how well prepared you are, nothing ever goes to plan.

I know this from five decades of experience … because speaking is part of the life of an author: if people don’t know about your books then they’ll never read them.

So you leave comfortable home; travel long distances to places you’ve never been before; meet 50 – or 500 – strangers … and hope it all works out in the end.

You know that every time it will be completely different: except for a couple of minor things. Like the fact that the person who invited you in the first place probably won’t turn up.

And, just before you rise to speak, an official will first take the microphone to read out a dozen very funny jokes they found on the internet.

Why then did they invite you?

You never get to eat the dessert and will definitely be the last person to leave the building.

This is because – if you engage with, say, 60 individuals after the speech, for only two minutes each – you won’t get to your car for more than two hours.

When you do reach the car park you find that everyone’s already left … sometimes, in isolated halls, you start to wonder whether it’s your job to turn off the lights and lock the building.

You can’t plan ahead because the things that go wrong are unique to each event.

Take the time the National Trust asked me to lead their members on a walking tour of Annerley Junction, visiting the scenes of my childhood I’d evoked in Over the Top with Jim.

Sounded like fun.

I’d show them my father Fred’s Lunns for Buns original cake shop where he made the Napoleons, rainbow cake, butterfly cakes, and his meaty meat pies; the Big Boys Playground at the Convent; underneath the Mary Immaculate Catholic Church to my first hidden classroom … the place where old Sister James taught me her trick to pronounce “three” correctly.

Then down to Ekibin Creek where Jackie and I floated our home-made corrugated iron canoes and fought a State School Kid gang with bows and arrows; the nearby quarry where we made our nulla-nullas with bitumen-and-broken-glass; and Junction Park State School itself “the home of our natural enemies”.

Plus, of course, the Lunn house up on timber stumps where my mother Olive ruled the roost over Jackie, me, Gay, Sheryl … and Fred.

Of course things had changed a lot since I was a boy in the 1940s.

Our first cake shop was now (appropriately) an antique store. But our second shop still baked all the delicacies Fred had … except now it was owned by Vietnamese.

Ekibin Creek now trickled beneath the six-lane M1 freeway to the Gold Coast; the Big Boys Playground was the site of a girls’ secondary school; our old Queenslander house had been moved to the bush and replaced by a two-storey brick one.

But, even so, the National Trust members and their friends wanted to see, with their own eyes, where I had gone over the top.

The month before the tour there was a sudden change.

The National Trust rang to say that 200 people had booked so they had stopped accepting any more.

“Hold on a minute,” I said. “I can’t take 200 people on a three-hour walk through Annerley. I can’t do more than a dozen! They’d never be able to hear me or see me!”

The highly efficient National Trust woman said she’d solved all problems: “We’ve hired a loud-hailer for you … and one of our members has volunteered to carry a stool for you to stand up on every time you stop to point something out.”

“But 200 people would disrupt traffic!” I countered. “We’d block roads and footpaths and entrances to shops.”

“It’s alright,” she replied. “We’ve checked with the Queensland Police and they said we could go ahead … provided our members don’t carry placards!”

The Trust was especially pleased that Queensland Arts Minister Matt Foley, no less, had booked a spot on the tour.

This only added to my impending sense of disaster.

But luck was surely on my side: soon after the swelling crowd gathered opposite Junction Park State School, a huge thunderstorm broke.

I was off the hook.

Many of these people, though enthusiastic, were older and in need of shelter.

However, before I could suggest we all go home, the generous owners of the adjacent Clansman Restaurant opened the doors and ushered everyone into the warmth and safety inside and served cups of tea.

What a great opportunity!

While the crowd sheltered from the storm, I’d tell them all about my childhood in Annerley in air-conditioned comfort! Everyone would be happy and, after the storm, we could all go home.

Unfortunately, by the time I finished my speech and answered many difficult questions – like “If you’re writing a memoir. How do you know what to leave out?” – the National Trust mob reacted badly to my suggestion we could now go home.

Typically, they wanted things kept exactly as they once had been.

It became mob rule.

People actually yelled out from the floor that they wanted their tour.

As we set off up the hill to Ipswich Road, a tiny old lady with an umbrella caught up to me and started tugging at my left elbow.

As I stopped and turned, she looked up with terror in her eyes and said: “Mr Lunn, how are you going to keep us all under control?”

Fascinated locals were hanging out of unit blocks and houses wondering what was going on in Annerley on a quiet Saturday afternoon. They had never seen anything like it: it wasn’t on the six o’clock news!

So I raised the loud-hailer, pressed the button, and shouted: “What do we want?... The right to march. When do we want it? … Now!”

Some residents applauded and others shut their door.

But the eyes of the little old lady next to me lit up: she was so impressed to see that I knew what I was doing.

“Old School” speeches can be the trickiest.

When I was Brisbane Bureau Chief of The Australian I was asked to address the annual Rugby Dinner of my old school: St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace.

Representatives of other GPS schools would be in attendance, as would the present Headmaster Brother Buckley plus my old Headmaster from the 1950s Brothers Adams: which added considerably to both the appeal and the pressure.

So I worked diligently on the speech all week and came up with one I was proud of – and with an impressive title too: “The Role of the Media in Society”.

They seated me at the head table between Brother Buckley and Brother Adams.

Then the MC got up to welcome everybody: “We are privileged here tonight to have author, journalist, Gregory Terrace Old Boy, and 1959 First Fifteen fullback, Hugh Lunn, to speak about … Rugby!”

Panic stations!

I’d assumed they would want me to talk about writing, about the media, about newspapers, about Rupert Murdoch, and about “the right to know”. But the abundant enthusiasm of the audience for the esoteric subject of Rugby – rather than the exoteric subject of the media – could not be denied.

While everybody else – including Brother Adams – downed their entrees: Asparagus Ribbon Crostini or Golden Corn Fritters, I ignored the food and started making notes on any rugby story I’d ever experienced or heard about.

Though feverishly writing, I did notice Brother Buckley was now deep into his Veal and Ham Pie, while Brother Adams had finished his BBQ Brisket with Orange Basil Yoghurt Dip, and was contemplating dessert.

Would it be the Brownie Mousse Stack or the Caramel Banana Pudding, or simply Almond Macaroons?

That was the moment when the current Headmaster, Brother Buckley, turned to me and, clearly mystified, asked: “Hugh, do you always leave it to just before you rise to write your speech?”

Before I could come up with an answer, my old Headmaster Brother Adams put his menu down, leant across me and answered the question in his charming Irish accent:

“Oh, Brother, young Hughie Lunn has always been the same. He was like that at Terrace. He’ll never change! Everything was done at the last possible minute. He always did his homework on the bus on the way to school!”

Bookshops – back when bookshops were ubiquitous – staged lots of events to attract customers to buy their (and your) books.

One sure way was to invite customers to “A Literary Dinner” to hear an author speak.

The missing link for the author is that “Literary Dinner” means different things to different bookshop proprietors.

Normally such an event is a dress-up, staid, hushed, affair held in large city hotels – the Hilton, Sofitel, Sheraton etc – so the ladies can get all dolled up for a quiet night out … or, for some, quite a night out.

But this was not so when I was invited to Toowoomba by a bookshop owner who obviously didn’t know the drill.

After my two-hour drive up from Brisbane, he drove me across the city to a sprawling hotel on the outer edge where I was ushered into a large canteen. Some dressed-up older folk were clearly present for my dinner – while everyone else was clearly there for their dinner!

I knew I was in trouble when the owner led me to the queue to load up my tray from the bain-marie.

There I found myself behind a woman pushing a baby in a pram.

The bookstore owner had brought along a microphone attached to a small portable speaker and set it up at the end of his extended table of guests.

Next to us was a table of athletic young men who turned out to be a Toowoomba rugby league team at their end-of-season dinner. Five minutes after I started speaking, they started yelling: “Keep the noise down, willya? We’re trying to enjoy ourselves.”

At least I realised I was creating a first.

The first time in Australian history that a Football Team Dinner had complained about the noise emanating from a Literary Dinner.

Problems for the speaker multiply the further you have to travel from home … and in Queensland that can be anything up to 2,000 kilometres away.

In the 1990s – because of the success of Over the Top with Jim – I was invited to be, as their invitation put it: Guest of Honour to Speak and Present the Awards at the Middlemount High School Gala Speech Night ... 1,000 kilometres from Brisbane

When I landed in the tropical city of Mackay, one of the parents – who was returning home with her weekly shopping – had arranged to give me a lift for the 3-hour drive to the purpose-built coal-mining town of Middlemount.

So I helped her load the car.

To my surprise, there were no motels or hotels in the town.

The school had arranged for me to stay in the miners’ quarters … which rather appealed to me because my parents had fallen in love in the kitchen of the Mt Isa Mines Men’s Mess in the 1930s.

By the time I was dropped off at the Principal’s house, I’d been on the go for seven hours, so I fell asleep on the sofa while around me the family got ready for the big Speech Night.

My job that night was to hand over all the cups and awards; make an inspiring speech which would set all these young Australians off on a good footing; then mingle with the teachers, parents, and good citizens of Middlemount until late.

By the end, I was really looking forward to my accommodation in the Miners’ Camp.

One of the parents drove me through town and pulled up in the dark outside a huge collection of low dimly-lit buildings a few steps above the coal dust.

A mine official showed me the massive Miners’ Mess where you made your own toast or cuppa, and then along a walkway which led to scores and scores of small adjoining cells: the single men’s sleeping quarters.

The lit walkways eventually converged on a large communal shower/toilet block at the back.

The first thing I noticed was that outside the door to every cell was a pair of huge steel-capped work boots covered in dirt. My shining black Florsheim moccasins, once in position outside my door, made me feel rather inadequate.

Inside my tiny room it was the absence of things that first struck me.

As I remember, there was no fridge. No toilet. No shower. No kettle. No cup. No tap. At least there was a single bed … but no chocolates on the pillow.

At the end of the bed was a large window to the outside world.

So, with nothing else to do, I walked over to admire the night sky because out west it is such a vast universe of everlasting stars that it overwhelms the senses.

But I was surprised: that night the sky was very dark.

All I could discern were two or three small stars.

Needing a shower, I headed for the deserted “Ablutions” block: but had no soap and no towel.

Luckily, a miner had left a block of Sunlight soap in a doorless tiled cubicle, so I used that, and then employed the old footy trick of briskly wiping all the water off my body with the palms of my hands.

In the tropics I was soon dry.

Now I had to get some sleep because in the morning I was being driven to another coal-mining town – Dysart – to do the same thing all over again.

Next morning I woke in darkness, but when I opened the door the sun was fairly blazing.

Confused, I carried my Florsheims back into my cave where I realised what was going on. The large window through which I had admired the night sky was in fact completely covered with a sheet of black plastic firmly nailed over the outside!

The stars I had seen through my window weren’t stars at all!

I’d been fooled.

What I’d seen from my author’s cell were tiny holes in the plastic which had been weathered and stretched and battered and crumbled by too-long exposure.

Was this a metaphor for the life of a writer?

David Mackintosh illustrations © profuselyillustrated.com

Great stories and illustrations which stir reminiscence and empathy in a fellow octogenarian.

Bain-marie is news to me. All this time I thought it was bay-marie? As usual I come away having enjoyed the yarns and learnt something into the bargain! 😊