The first bore sucking precious water up from deep below the surface is a full 20 miles out of Dajarra, like an oasis in the desert, and drover Chris Herrmann wants to make it by nightfall.

“I remember there’s good water there,” he tells me as I take notes.

“That bore’s got taps on it like an elephant’s mouth.”

The bore turns out to be a giant windmill which plunges an iron rod up and down under the earth, sucking up the underground water that abounds.

Chris says that if there were enough of these bores there would be no water problem out here in the Red Centre, but they cost $25,000 each. In fact, this is what the stock route is all about: it leads from one government bore to the next.

The water here flows into a round earth “turkey’s nest” dam … and from there into a very long cattle trough where the level is controlled by a float.

You don’t need fences out here, Chris says, because cattle can’t move much further than six miles from a bore. “The number of cattle a property holds in the Outback depends on the number of bores,” he says matter-of-factly.

The water in the muddy dam looks cold and inviting after an all-day dusty journey under an unforgiving sun, so when the hessian yard is built everyone sloshes in for a swim, wading through the knee-deep red mud: except Chris Herrmann.

He has – from years of yelling in the bush – a voice capable of causing pain to anyone too close: the ringers have forgotten to wash the backs of their horses and come in for a distant verbal lashing.

To me we have plenty of horses – 11 of them. But Chris is worried because one is already limping.

“You should have four horses a man for droving and we only have two and half. So we can’t afford to let them get sores on their backs from the saddles,” he says.

John Cobbo is one of the ringers and there is a white jackeroo, John Kunze, too.

“John the blackfella, you wipe up; John the whitefella, you wash up… no racial discrimination here,” Chris yells.

These names are to stick for the whole trip.

It is August 1974, and round the campfire Chris Herrmann, a Queenslander, tells stories about some of the rough-tough blokes he has met in the Northern Territory. He is particularly fascinated by one character who has never worn shoes in his life: “He even wears spurs on his bare feet!”

As he is to do daily on this trip, next morning Chris mounts a horse with a ringer on a horse behind him and counts the cattle out … he doesn’t want to leave any behind.

The eerie galah-breast redness of the central Australian sunrise with the silver egg-shaped moon dying in the opposite sky is broken only by Chris’s lonely cries of “hundred” as the man behind him counts off the hundreds.

If any of the Droughtmasters are missing the horsemen will have to go back and look for them.

The cattle continue all day through giant red ridges topped with smooth red boulders … or they pass impregnable fortresses of rock.

The two motorbikes go on ahead looking for the next bore – and come back: they can’t find it!

Everyone, including me, looks at Chris Herrmann hoping he has the answer. He pulls out the pencil lines he has drawn in his little green book: “No worries,” he reassures us. “Ten to one it’s that second ridge out yon. Anyway, we’ll know directly.”

Rolly, the eldest son, has gone back east and his younger brothers Steve and Alex, only teenagers, are suffering on their motorbikes.

The aptly-named spear grass is more than a metre high in places and its tiny arrow-like spears jab through their clothes and even penetrate their boots. “You won’t feel them after a couple of days,” Chris assures his sons. Then he whispers to me: “They’ll still be getting them out in six months.”

The cattle don’t like being pushed through the giant castles of spinifex, and even the motorbikes can’t take it.

Their tyres keep going flat – the spinifex needles are so sharp they keep puncturing the tyres.

Meanwhile, Chris decides to head off in the Tilley to look for a better track. I am about to be left alone, so I ask how long he’ll be? “I’ll tell you when I get back,” he says.

Even though it is still winter and very cold at night sleeping on the ground in the open, it’s very hot during the day.

My nostril linings have dried out and my lips are cracked.

No one else seems to be suffering, yet, but then I can’t drink as much water as they can.

My first mouthful of bore water was so foul I spat it out on the red dust where it immediately disappeared. Even after practice I can force down only the occasional mouthful.

Little do I know that farther out the water gets much worse.

I tried to buy some cordial in Dajarra but they didn’t have any. Even the tea tastes sour, and an oily scum forms on the top which sticks to the side of the chipped enamel mugs we use.

Hours later, we cross a rise and Chris sees the bore in the distance, but, even though he points it out, I can’t see it. I have not yet learned to spot these straight man-made shapes in a land of grass and small twisted trees.

He stops for a moment to digest his success and looks out across the centre of Australia and addresses us all from his horse as if he were the leader of a team of early explorers: “We’re out of the mongrel country! Look, the Land of Plenty – plenty of spinifex, plenty of bulldust, and plenty of borewater.”

We’re running late, so Chris and I go on ahead in the Tilley to check the bore.

This bore has a set of yards which will hold our mob. “A gift from that fella above,” says Chris. “The bee’s knees.”

The view from the yards as the sun sets is an uninterrupted 360 degrees of rugged red hills running in long ridges. The sunset has the same impact as a beautiful girl walking into a pub: the orange and red looking like a bushfire on a far horizon.

I am sitting alone at the camp waiting for the others who are pushing the Droughtmasters towards the bore as fast as they can. Except for the distant cry of the drovers all is silent, and alone, and half-light. There is a feeling of being in church. “Hoo, you beauties, work up, work up! Oi Oi! Come on you buggers!”

It’s after 8 and very dark when the cattle finally arrive by moonlight and thunder past me, shaking the ground.

As everyone rolls out his swag by the yards and heats his quart-pot (oval-shaped billies for tea), Chris is unhappy about the cattle getting to the bore so late.

Because of the spinifex, and the rough ground, two horses are now lame and one is sick.

“We wouldn’t want to hit the old man spinifex too much or we’ll never get through.”

As he pulls his hat down further to keep the moonlight out for the night, he adds as a final word: “The way we’re going we’ll all have to ride the same horse.”

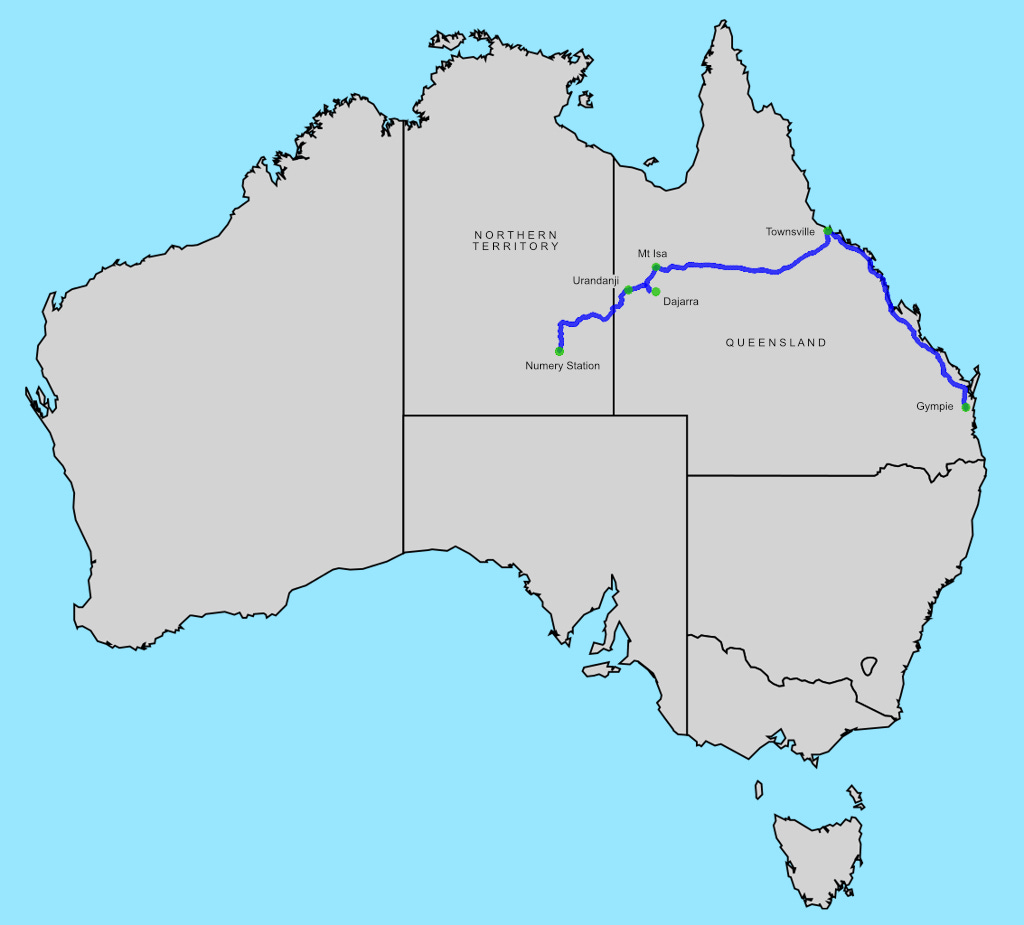

Like an Arab caravan moving through the desert, we continue across central Australia, droving the red river of cattle from bore water to bore water.

It is getting much hotter and the flies are starting to appear under a sun that now burns like a Gold Coast beach on Christmas Day.

The next windmill sucking water miraculously from beneath the parched earth is 10 miles away and yet it is visible on the horizon: if you know where to look. The tallest shapes in central Australia, they stand like giant sentinels guarding life in the Centre.

They keep alive the cockatoos on the dead trees and the sheep-sized eagle-hawks nearby. Plus the hundreds of red-beaked finches that live around the bores. They don’t bother to fly away; man doesn’t harm them here.

Because they fly so dangerously close, Chris Herrmann calls them “brumby birds”.

One of the Droughtmasters is lame and limping badly and Chris says he may cut a horse-shoe in half for her cloven hoof and shoe her.

He says the men are pushing the cattle too hard and yells above the herd: “You’re droving, not driving!”

He turns to me clearly frustrated: “City people think droving is a flash name for driving. I don’t care if it takes an extra week to get there – I want to make sure the cattle get there in good condition.”

Some dark clouds appear from nowhere and Chris says it’s a bit of a worry.

“Any amount of rain at all and we’d have to leave the Tilley behind because of the bulldust. It’s so deep I have my sixty-foot tape to measure it with,” and only half grins.

He is also worried the men will get dysentery from the bad bore water, which could hold him up for two or three days. He has cornflour to bind us up if necessary.

One ringer is already on it.

At the next bore, the cattle fight to drink around the float because they know that is the new water from the deep and therefore the coolest.

They always run the last mile to the bore because they can smell the water up ahead.

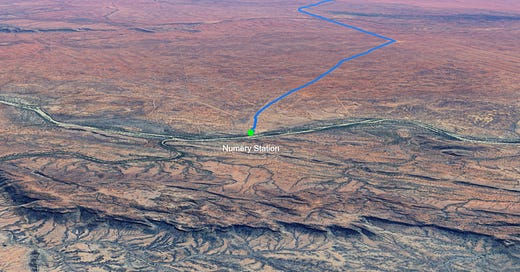

Chris Herrmann relaxes after washing his face in the trough with the cattle. He says he has never done much droving, but two months ago he walked a mob of bullocks more than 60 miles from Numery Station into Alice Springs in ten days.

“It was the first droving mob they’d seen for years,” he said.

Realising that I’m making notes, a man building a new water-trough tells me I should find and interview “Territory Jack”.

“He’s a real, typical Aussie,” the man says. “Hard-drinking, a rough bony fella, tells big stories. His trousers hang down the back. His wife beats him with a stick. A real, typical Aussie.”

Chris pulls a face.

“Do you know Territory Jack then?” the man asks him. “Know him?” replies Chris. “I’d know his bones in a stew.”

“The bikies”, as Chris Herrmann calls his teenage sons Steve and Alex, have to clean the dust out of their air filters and fix more punctures before the next day’s trek.

Steve can run rings around a horse, and rides flat-out through the open country. Some bumps send him into the air but always he stays on. “I wouldn’t be out here without the bikies,” Chris Herrmann says. “But you still have to have good horses.”

Chris decides he must re-shoe one of the lame horses to try to fix her sore foot.

He gets out a hammer, a file, a bundle of long sharp flat nails, and horseshoes in as many sizes as a set of golf clubs.

When he is about to begin, he mutters, as he usually does when starting a tough task, “There was movement at the station …”

He picks out a pair of horseshoes that will fit and grabs the horse by a front leg and bends over, holding the hoof tightly between his knees. After a tug-of-war with the horse Chris loses his hat, and that was when I first noticed that his face might be red … but his forehead is pure white.

Chris – holding the leg steady and with two hands – begins to file the hoof.

When it is nice and level, he files a niche in the back where the shoe fits and begins to drive six of the chisel-shaped nails into the hoof.

These nails are shaped to bend outwards as they go in, so putting in the two side nails is dangerous because once through the hoof the nails stick out the side. If the horse should pull his leg back between Chris Herrmann’s thighs he will be badly cut.

It's a common accident, Chris tells me, and that is why he first establishes with the horse – by words and actions – that he is the stronger of the two.

When the nails protrude more than an inch out the top of the hoof he breaks them off.

Meanwhile the ringers are circling the cattle in the late afternoon while the Droughtmasters rest and feed.

Making tea in the shade of a tiny tree Chris Herrmann tells me of his life in the bush and why he loves it so much. It all comes back to his oft-repeated mantra: “There’s no one to ’noy ya – no salesmen, no religious cranks.”

Because the water out here makes the tea taste bad, I have turned to drinking Milo: it’s marvellous what a difference Milo makes.

But this means I have to get some of the boiling water before the tea leaves are dropped in and the pot lifted quickly from the fire and kicked with Chris’s size eleven boots to settle the leaves to the bottom.

So Chris casually lifts the boiling billy out of the flames, puts his bare hand underneath, and tips some water into my Milo mug.

He has a gentle quality when not working, and talks less stridently and with plenty of dry bush humour.

When washing-up time comes he tells of the drover he once knew who had one lot of utensils and a dog: “The dog was to lick the utensils clean.”

Then he tells how dry it can get in the Northern Territory.

“One fellow’s property in a big drought could only support two black cockatoos and four kangaroos – and he had to move the kangaroos on to another bore.”

At dinner, Steve is making a stew and complains the corn beef smells a bit. “In that case put it in quick,” says Chris.

That night, flying cobweb strands with white spider eggs attached blow across the desert above the camp and wrap themselves around the Tilley’s aerial in their gleaming hundreds.

I watch them pass above my swag in the moonlight: spiders spreading silently through the Outback.

There are many kangaroos and hundreds of cockatoos, galahs, and finches around the bore, plus wild brolgas that seem to dance in panic. Some emus duck under a barb-wire fence. I remark how easily they do it.

“They move like wind through a barb-wire fence,” muses Chris.

What a fab life you have led, surely a few autobiographies coming up

“The word has passed around” - great reading -

Gay S.🦅