Fifty years ago, I was shopping in Myers Department Store in Brisbane when a customer came up and asked, “Do you have these sandals in size 7?”

This happened to me a lot.

Perhaps it was because as a reporter I was an office worker who always dressed in suit trousers, Florsheim moccasins, a white shirt and wide tie, with a biro in my breast pocket.

But every now and then (despite not being qualified physically or mentally) I had to become someone else: someone who could survive a war, a cyclone, a revolution, or the mangroves of Cape York or New Guinea

This time, I was in Myers looking to buy a swag because I was heading off on a story into “the Never-Never” … the remote deserted interior of the Australian continent.

The Myers saleswoman took me to the haberdashery department and pointed to an enormous horizontal curtain of crimson velvet with gold fringes and tassels.

Obviously, no one in Myers knew what a swag was – and, to tell the exact truth, neither did I.

Myers, who sold everything worth having, didn’t have what I needed.

The Australian newspaper had given me yet another difficult distant assignment. “This mad Queensland grazier says he’s going to drive 800 cattle 500 miles through the Outback to the Simpson Desert in the interior,” the Editor said.

“It’s the Last Great Cattle Drive now that road trains have taken over, so it’s a good story. But he warns it’s vast, remote, arid, and unpopulated … so Hugh get yourself a swag cos you’re sleeping on the ground with the cows for the next few weeks.

“Oh, and by the way, those 800 cows include 60 prize bulls.”

I was more worried about the huge venomous snakes the Outback is famous for … a road train driver had told me the previous year that he would only get out of his cabin when wearing hip-high boots.

Unable to find a swag, I bought a thick foam mattress, wrapped it in half a dozen blankets and then manhandled the result into a giant unwieldy jam roll … tied with a dressing gown cord.

I’d heard it gets freezing in the desert once night falls.

I arranged to meet up with the drover and his six ringers (the men who ride around and around the cattle to keep them under control) in the tiny western Queensland town of Dajarra.

The 800 huge humped beasts – many taller than me – arrived in Dajarra after eight days on a train: rushing out of the jolting wagons like a Saturday night crowd leaving a film and racing to catch the last tram home.

I wondered at their enthusiasm: neither they nor I knew what was ahead of us.

Dajarra is as deep as you can get into the Outback on a train. It is also the furthest town west in the giant state of Queensland – that is if you don’t count the tiny outpost of Urandangie.

Urandangie is more than 100 miles further towards the red centre … and soon our little expedition would set out to drive the cattle from Dajarra through Urandangie into the Northern Territory to Numery Station on the edge of the Simpson Desert.

The drover, a bloke called Chris Herrmann, hadn’t arrived as expected in his “Tilley” – which I soon learned was the name for a Ute in the Outback.

We couldn’t start without him. There were no signposts on that 19th Century stock route so we would never be able to find the few waterholes along the way without him.

With no water, the cattle – not to mention us – would perish.

So, that hot August 1974 morning the three Aboriginal ringers – Robin Cobbo, 60, his son John Cobbo, 25, and Ted Hornet, 35 – sat in the gutter with me in Dajarra waiting for Chris Herrmann.

Chris was bringing two of his sons Steve, 17, and Alex, 12, to work as ringers.

So we needed them too.

We could have gone for a drink in the pub opposite but none of us – carrying swags and dressed for weeks in the desert – felt we’d be welcomed. A sign on the door read: “We ask you to assist us to maintain a reasonable standard in this bar by being fully clothed.”

Dajarra was full of the wrecks of old cars which found the conditions out here too trying. But it bustled with government carpenters building rows of new homes for Aborigines coming from distant cattle stations to live in town.

Robin Cobbo could not quite believe that a writer, of all people, would be travelling with them on such a journey. He’d never met a writer before.

“What ya gonna write?” he asked with genuine interest.

I told him I as yet had no idea.

So Robin decided to start my story for me:

“You sat on the footpath in Dajarra and three crows played in the main street,” he dictated, summing up the scene admirably.

Next morning we were still waiting.

We’d set up camp in the open next to the Dajarra cattle yards, despite the stink. A cow had been dead in the yards for a week but no one had bothered to remove it.

Crows and hawks fed on the body.

Robin pointed at this scene and then at my notebook raising his eyebrows … as if I were missing something.

Unknown to us, Chris Herrmann was having problems of his own.

Normally he ran Nummery Station for Richard Apel, the grazier who owned the 800 cattle.

As Chris Herrmann left Nummery Station in his Tilley, he found a windmill bore that wasn’t working. Without it, all the cattle in that area would soon die, so his son Steve rode his motorbike 160 miles for replacement leather valves which lift the water up from deep underground.

When their Tilley reached Queensland, the soft bulldust hid a deep hole and the bump broke a U-bolt which had to be repaired on the spot.

No garages out there.

Chris Herrmann wanted to let us know he was delayed, so he stopped at the Post Office in Urandangie (one of only two buildings in the town) to send a telegram … but was bitten by the dog.

He emerged with blood running down his leg having ascertained there was a telegram strike for the first time in history.

The next day, with no drover in sight, the grazier, Richard Apel, flew in to tell us, “The cattle have had a good rest, and it’s getting hotter every day: you’d better get going without him.”

Apel then flew his single-engine plane off to Numery Station, which he was looking after in Chris Herrmann’s absence … while, without a drover, we headed out into the vast unfenced unknown.

No cafes, no cappuccinos, no salad lunches, no means of communication, no drover who knows the way, and no Tilley.

And me humping a swag twice the size of my body.

The oldest son Rolly Herrmann, who had arrived with the cattle, was now in charge. He couldn’t find the old stock route so just headed due west … between small red stony hills, aiming to get as far as possible through this difficult section of slippery slopes on the first day.

All day I tried to get used to the scene as we emerged out of the hills onto a wide brown plain that stretched as far as the eye could see in any direction – no roads, no structures, no trees, no cars, no people, no music, no power poles, no noise … not even talking.

Just the pleasant soft rumble of the hooves of the11 horses and 800 cattle.

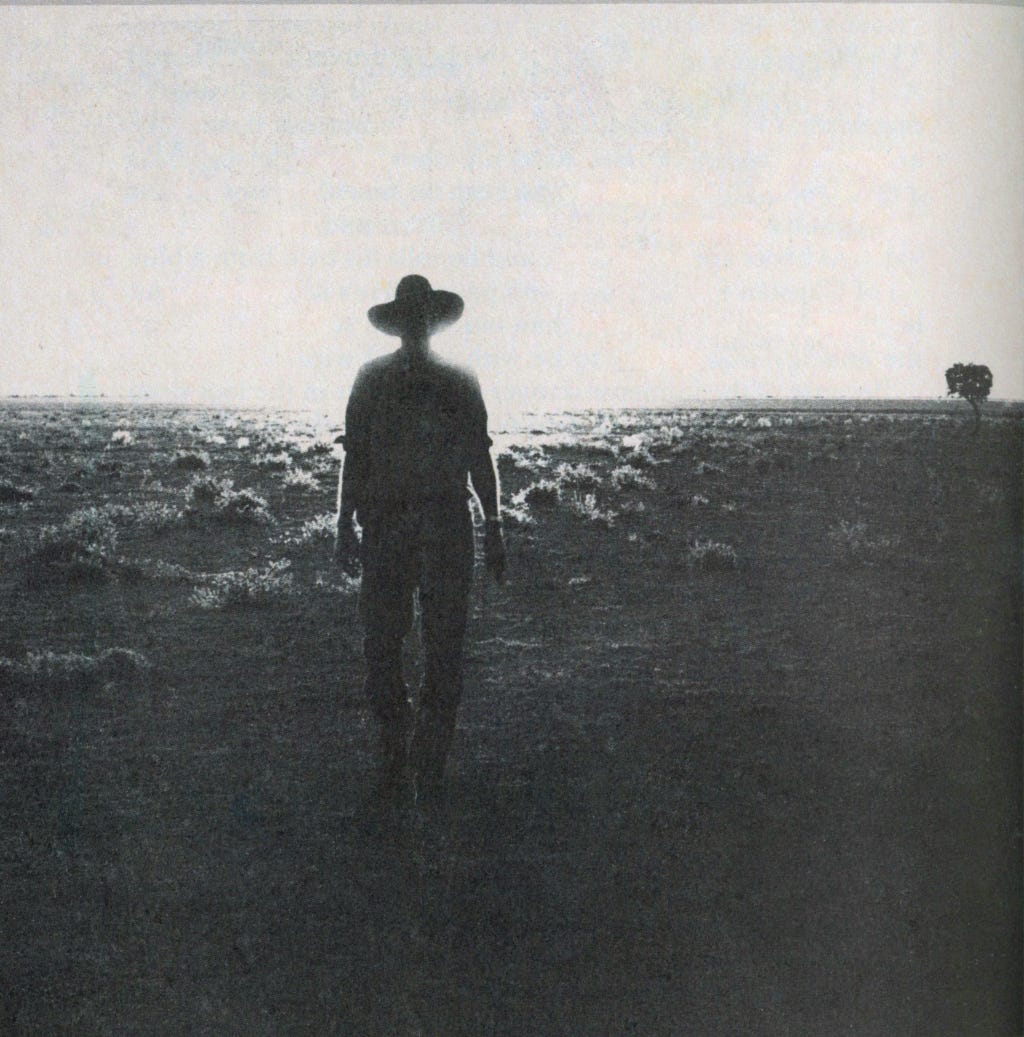

Next morning a human being appeared out of the rising sun … walking towards us on a plain so flat that it was like standing in the middle of a giant penny. He had the tall, lean gait of Gary Cooper. His face was a central Australian red. His pale blue eyes peered out from under a shadowy hat.

It was him: Chris Herrmann, the drover.

He was yelling as loudly as he could: “You’re going the wrong way!”

Apparently, we were on track to miss the first waterhole by several miles.

Chris Herrmann was in his 50s, but his stomach went in rather than out. The only place he bulged was in the forearms, where muscles stood up like ropes and worked seemingly independently of his body.

If I said he was wiry, the analogy would have to be with barbed wire.

Everyone was relieved to see him … until he took one look at me and said: “That’s the biggest bloody swag I’ve ever seen!” (I had noticed everyone else’s swag was the size of a rolled blanket.)

“How many of you are there?” he demanded.

“Anyway, who are you? Ten to one you’ve never been out here before!”

I wondered how he could tell.

Clearly Richard Apel hadn’t warned him I was coming.

“I’m a feature writer for Rupert Murdoch’s The Australian newspaper, his foreign correspondent in Queensland,” I explained.

“The Australia? Never heard of it,” Herrmann said.

“Can you cook?”

It was 1974 and cattle prices had fallen by half in the previous 12 months, making the old-time drover suddenly a more economic proposition than the modern road train.

Drovers, and ringers, and jackeroos once again dusted off their rusty, haunting Condamine bells, their horse hobbles, and their quart-pots … to re-open the great stock routes across central Australia.

Back at Dajarra, Richard Apel had told me that just a generation before, so many beef cattle passed along this stock route from the Northern Territory into Queensland through Urandangie that folklore invented the phrase: “the dust never settles in ’Dangie”.

In 1950, a total of 122,212 head of cattle had passed through ’Dangie in eight months – wading through the flour-like soft red bulldust in the middle of Australia’s Never-Never, 300 miles south of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

But by the early 1960s road trains – which had to travel much further out of the way to stick to the bitumen – had taken over and ’Dangie never saw another ringer or a drover.

We would be the first in a decade.

Meanwhile, the town’s population had fallen to seven (when everyone was at home) – including the owners of the other building: the ’Dangie Hotel.

Our 800 cattle had started out in southeast Queensland at Richard Apel’s Mimosa Stud.

Because the Northern Territory was disease-free, the 800 had to have all ticks removed and be tested for TB and brucellosis.

Testing took a full week, but because some had been immunized when young, they reacted and had to be retested – putting the whole operation a week closer to the burning summer months.

There was a further delay when a miscount had Apel searching far and wide for 100 head … who were there all the time.

This made the journey into the scorching interior that much more dangerous.

Normally, cattle only moved from the Territory into Queensland; not the other way. But with his 60 prize bulls, Richard Apel wanted to build a Droughtmaster Stud herd that was indigenous to the Territory … so he could supply disease-free Droughtmaster cattle locally.

Apel had huge faith in “good bulls”.

“My father used to tell me, ‘If you want to do a bloke a bad turn, don’t sell him a bad bull … give it to him’.”

Richard Apel believed the Droughtmaster – a breed developed in Australia to have high heat tolerance and tremendous walking and foraging abilities – was the ideal beast to conquer the Outback.

The Droughtmaster was five-eighths Brahman (the hardy Indian breed with the hump on the neck) which resists drought and ticks and disease so well … and three-eighths British Shorthorn.

“If they were pure Brahman, you’d never round them up once you let them loose out there,” Apel said.

The cattle started from Mimosa stud on a train that puffed 700 miles up the coast of Queensland to Townsville.

In the middle of the night one of the wagons caught fire north of Rockhampton when an axle seized and the oil boiled. The panicking cattle had to be moved into a new wagon – another extra day.

Then a cow in one wagon went down and Chris Herrmann’s oldest son Rolly, who was leading the train journey, climbed in to save it from being trampled … but was kicked several times for his trouble.

He tried to winch her up with a rope made from the girth of his saddle, his reins, and his bridle but the cow was too heavy. So an enthusiastic young ringer grabbed an electric jigger to give the cow a shock, but there was a loud yell which sounded awfully human.

Rolly copped the full bolt in the leg.

From Townsville the train headed west to Prairie for a three-day stop to rest the cattle ... and Rolly. There, it was discovered that the downed cow had a dislocated hind leg and it was put down.

The arduous journey was already bringing on calves and there were three who would not be born on Numery Station as Richard Apel had hoped.

These baby calves would never make the journey … so a man with milking cows gratefully accepted them.

Chris Herrmann stood on the last small rise gazing into the distance looking for what was once called The Overlanders’ Trail.

I asked what he could see out there that told him which way to go? There was nothing to guide us. Plus he didn’t even have a compass.

I couldn’t see anything!

“I know where I’m going,” Chris said … “I got full with a surveyor once.”

He said we were going to be the first droving team from Queensland into the Northern Territory since beef cattle were first taken west in the1800s.

I asked, notebook in hand, how long our journey would take.

“Out here, cattle have to be very good to average more than 10 miles a day in these hot, dry conditions … so it should take us at least seven weeks,” he replied.

In all, this was a 2,000-mile journey to restock Apel’s 2,100 square-mile Numery Station – a trip as far as from London to Moscow.

Richard Apel believed that by using staff labor as a droving team he could move the cattle for about $11,000 instead of $40,000 by road train.

Plus he hoped his Droughtmasters – by walking slowly and eating as they went – would arrive in much better condition than standing up in fast-moving semis.

On the other hand, he could lose hundreds of head of prime cattle (not to mention this writer) on the expedition if things should go wrong (no communication, no helicopters, no mobile phones in 1974) in the middle of nowhere with no one anywhere near close enough to help.

And because droving is, by nature, a very slow process, there was plenty of time for ghastly things to happen.

The biggest risk on this trip was black gidgee poisoning – if cattle ate the leaves of the small black gidgee trees that were everywhere along the track, it would send them raving mad and kill them.

“If they should take to the black gidgee we could lose 50 head, and that’s without stretching it,” warned Chris Herrmann.

“With cattle you always look on the optimistic side. One bloke lost 100 bullocks in one lot droving through here, all to the black gidgee.”

Another ever-present threat was a cattle rush – or in American movie language a “stampede”. But I never did hear that word used out west.

“If a big mob of cattle hear a strange noise in the night they can be up and galloping within two paces … and no fence will stop them,” Chris warned me. “I’ve seen 40 cattle killed in a rush.”

In 1963, 300 head from a mob of 1,000 were staked by scrub timber or trampled to death in what Chris Herrmann called “a terrible rush” – when the Duracks drove their cattle in the same direction we were going.

But Chris refused to bring dogs out here to help control the cattle because there were no enclosures … but plenty of wild dingoes.

He had his own plan to beat the threat of a rush.

Packed in his Tilley were a couple of hundred yards of six-foot wide hessian and a pile of steel posts. Each night, instead of exhausted ringers on tired horses riding around and around the 800 cattle, Chris built a yard out in the middle of the deserted outback.

And took it down in the morning.

“No worries.”

Not that it would stop a rush – nothing will apparently. But the cattle could not see out and, as for noises, he had his own unique solution.

Surprisingly, we could pick up a radio station out here, and Chris placed transistor radios on full volume on opposite sides of the cattle and set both to an all-night station.

“Slim Dusty’ll drown out any sharp crack,” he said.

“The biggest danger of a rush is in drummy country (where the ground sounds hollow). You get a feeling about cattle and places after a while and, ten-to-one, she’ll be right.”

But nevertheless, we slept on the ground with the Tilley and the fire between us and the cattle.

Two things were on Chris Herrmann’s mind that starry, starry night. Although the cows had been specially chosen because they were not due to calve, the journey could bring more calves on.

Then there was the terrible prospect of bushfire.

“That would be a worry,” says Chris. “One thing’s for certain: we couldn’t stop it.”

While Chris spoke, I observed him: so tough he made John Wayne seem a pansy.

He was not broad-shouldered, in fact, except for the giant talons which were his hands, he could have been a film star portraying the archetype bush Aussie of a century ago.

He wore his broad-brimmed hat so much that he looked strange without it on – like a bearded man who has suddenly shaved. In a bar, and even in bed in his swag on the ground at night, Chris wore his hat “to keep the moonlight out”.

His boots were size 11 and he rolled his own from a blue tin of Capstan in white TALLY-HO papers.

Because of the immense danger of bushfires in the foot-deep dry grass stretching in all directions as far as the eye could see, Chris stubbed out his cigarettes in the palm of his left hand, after giving it a cursory lick first.

The odds on anything happening were always “ten-to-one” and there was very little around that was “worth more than two bob”.

But he would never win a gunfight in a Hollywood cowboy film – his giant fingers just wouldn’t fit through the trigger guard on a Colt .45.

One of the first things I noticed about this ageing drover was that – instead of a briefcase – he carried his green notebook and pencils and all his belongings in a green steel .303 cartridge box.

Bazza McKenzie is Melbourne’s version of the archetypal Aussie so his suitcase overflows with cans of Fosters beer. But Chris Herrmann’s cartridge box was filled with round tins of tobacco for the long droving trip.

There are no double-breasted suits in the west either and so Chris wore tight blue jeans that made the circle of his tobacco tin stand out below the leather pouch that housed his ever-present pocket knife, which he used often.

Never far from his favoured left hand were his stock-whip and long white lasso.

One of the two pockets on the front of his khaki shirt (sleeves rolled to the elbows, of course) held the green diary which contained the little maps Chris had drawn to get the cattle safely across Australia’s parched centre.

He will need that stock-whip and that lasso – and those maps – before he finishes this journey, driving the cattle from one waterhole to the next past the ever-present intensely thorny spinifex bushes.

For though Chris Herrmann instills confidence in his men with his conditioned reflex cry of “no worries”, cattle do die, and so do their calves, and seven of the 11 horses will be too lame to ride before the end of this tortuous trip.

Did your swag make it all the way to Numery Station Hugh? Sounds like it would have been comfortable with the thick foam mattress and six blankets on a cold desert night.

Love the story. You are a braver person than I am. I couldn’t go on a Drovers run in the Outback. But my husband whose grandparents owned a dairy farm would have loved to go on a Drovers Run. I was amazed by the $$ difference in 1974 to move the cattle overland rather than take them by road train. Also interesting it was the first Drover’s Run in 10 years.