In December 1980 I was distressed to read a tiny reference in the In Brief column in the local Brisbane Courier-Mail.

Former Queensland cricket international Ken Mackay is seriously ill in hospital after a heart attack.

Nothing more.

Not even a mention in his hometown newspaper of his universally known nickname of "Slasher".

Yet this was the same newspaper that – back in the amateur cricket days of 1963 – was smothered with one shilling pieces when it ran a "Bob in for Slasher" campaign on his retirement … calling for donations of a shilling each for the state’s cricket hero.

They were inundated with silver shillings – 400,000 of them – from Slasher’s adoring fans.

Including me.

It was a sobering thought that the life of a cricket hero who saved Australia and Queensland from defeats so many times could – within just 20 years – be worth only one sentence in his hometown paper.

So I sat down and wrote the following story for The Australian …

We all believe that Australia remembers its great sporting heroes. Look at Don Bradman: honoured as a Knight of the Realm; christened “The Don”; a Don Bradman Museum and International Hall of Fame in Bowral dedicated to him; his image appearing on stamps; focus of a television mini-series; on TV in anything intended to remind us of our boundless past.

But to remember one hero is to forget many.

What about Ken “Slasher” Mackay who should stand as a symbol of the lost Aussie hero: a man whose name appears rarely in the record books but whose performances when he was needed exceeded the country’s highest hopes.

A Man from Snowy River type you could always warrant would be with you when he was wanted at the end.

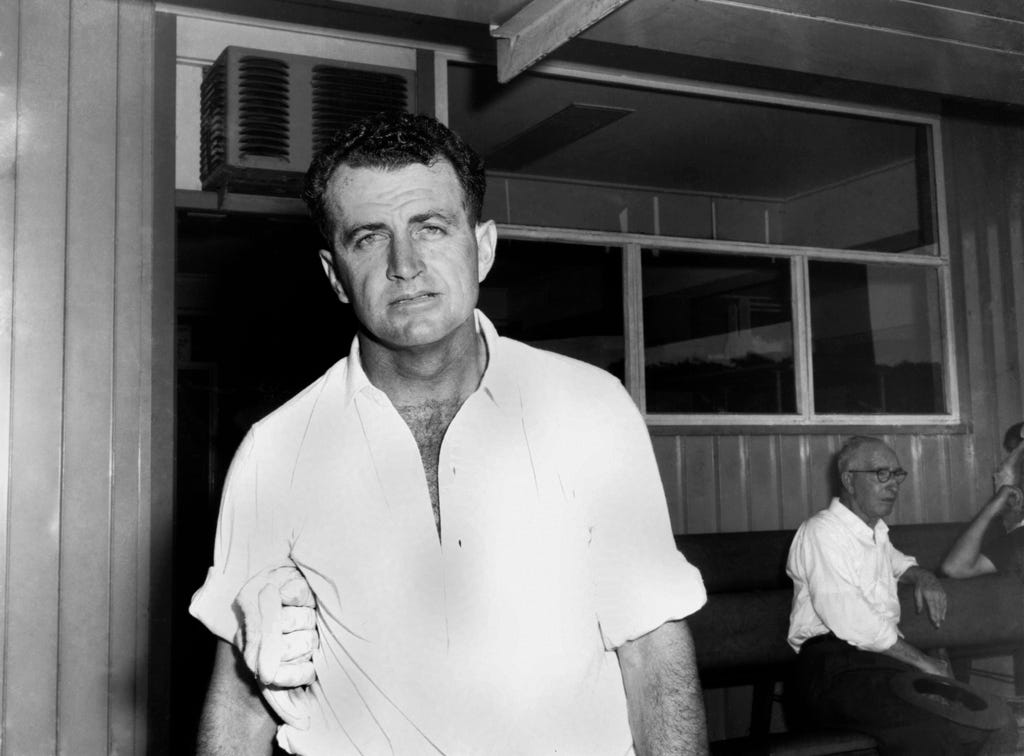

Slasher Mackay was, no doubt about it, not your normal hero.

He shuffled along in a gait so unlike Gary Cooper's that one English critic wrote of him that he could “forgive a man for limping, but not on both legs at the same time”.

Slasher didn't stand tall and poised at the crease. He crouched awkwardly over his bat, both legs bent more than might be expected, and gazed through two slightly droopy eyes face-on down the wicket.

He even crouched when he bowled.

His forearms and wrists gave no indication of strength – far too thin were they for a sports hero. So he didn't lift the bat backwards in a flourish before crashing the ball through the field with a loud thwack. In fact, contrary to all the rules of batting, he didn't take it back at all.

"This man doesn't hit the ball, he squirts it," English cricket captain Peter May sneered when he first saw Mackay bat.

And all the while he batted, Slasher chewed and chewed and chewed on gum … a singular characteristic which made him even more of a hero to his millions of admirers. He was like a comic book character: the duckling who turned into a swan; the weak boy who won the interschool championship for his school from an impossible position.

When a cartoonist drew him preparing for a Test match against England he had Mackay packing his kit bag: spiked cricket shoes, pads, bat, gloves, cap – and a huge box of chewing gum.

Perhaps it was because he didn't look like a champion that Mackay took so long to make his name.

Much longer than he should have.

As a schoolboy for Queensland against the other Australian states he averaged more than 700 for the series – out only the once.

He made the Queensland team again as a senior but could advance no further into the national team … even though for years he was among the top one or two run scorers in the country.

Some said he was too awkward; others that he scored too slowly; still others reasoned he would never get away with his peculiar style in international Test cricket. Anyway, they said, the crowds didn't like him.

And this was true then, at least in Sydney.

At the Sydney Cricket Ground, Mackay’s arrival at the wicket was inevitably greeted with cries of "Where's your mattress, Mackay?" … perhaps not so much because he scored so slowly as because they knew he would be out there for a very, very long time.

In one of those matches in Sydney for Queensland against New South Wales, Slasher scored 203 in the first innings and 169 not-out in the second.

This was why he was so loved in Queensland.

Mackay, it must be remembered, was always batting for our losing side against the best bowlers in the country. Which was why he would sometimes bat for the first two days of a four-day inter-state Sheffield Shield match.

He was an intense competitor, a Queenslander through to his underpants whose stated ambition was to one day carry his state to its first-ever Sheffield Shield championship.

He almost did this once when Queensland had to score 140 at better than a run-a-minute on the last afternoon against the might of the most populous state, New South Wales, in the last match of the season.

Mackay sent the radio airwaves mad as half the country tuned in to see if it could be done against the best team in the nation.

Instead of coming in at his customary position of third batsman, Slasher opened the batting – attacking the two Test bowlers Benaud and Davidson and scoring 96 in record time. But, after he was run out in his desperate bid, the team faltered and lost.

When I was lucky enough to have lunch with Slasher at Milton Tennis Centre, he told me that he pushed and prodded at the wicket because he didn’t want to give his wicket away cheaply. He didn’t want to throw away any chance of victory.

Looking out over the Centre Court at Milton, I remarked that nineteen-year-old John Newcombe had done marvellously well in his first Davis Cup to take each of the American champions (Ralston and McKinlay) to five sets in the singles.

Mackay turned to me with those sad eyes and replied simply:

"No he didn't. He lost both."

In the end, this never-say-die attitude took Slasher into the Australian Test team. Sheer weight of runs after 10 years in the state side could no longer be ignored and he was picked for the tour of England in 1956, aged twenty-nine ... which in those days was almost over the hill.

Australia was about to get another idol, if a very different one from the rest.

An English spin bowler named Laker was wreaking havoc on England’s specially prepared dusty spinning wickets when Mackay was finally named in Australia’s team for the first time … for the Second Test at Lords in June 1956 in London.

Slasher, too, found it impossible to play Laker on the savagely spinning wicket – but doggedly stayed in, hour after hour after hour.

It would not be true to say "batted on" because Mackay found that it was very dangerous to use the bat against Laker – the ball was too likely to fly with the spin up in the air. Wireless commentators told an enthralled Australia that Mackay was hitting the ball with everything: "pads, shoes, elbows, hips, chest – anything except his bat".

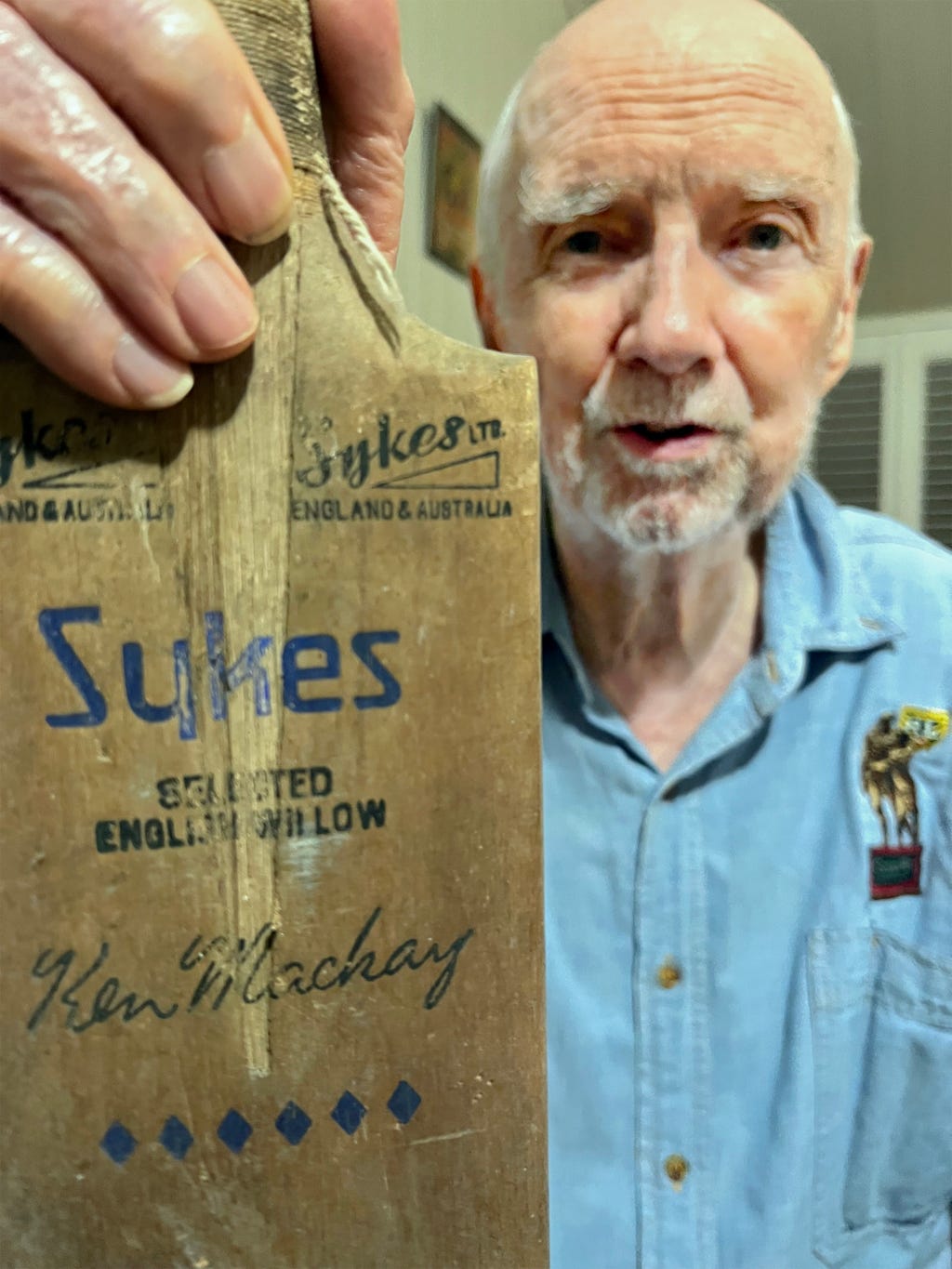

In that match Slasher was to set a couple of unheroic records: he became the first man to bat for more than seven hours in his first Test match. Wisden still lists him in its record books, if only for the following: "Slowest innings: 31 in 264 minutes, K. D. Mackay, Australia versus England, Lords, 1956."

Slasher, good old Slasher – so named because of his notorious slow-scoring – won Australia that Test: the only Test win of the tour.

Former England captain Len Hutton said in an interview after that Lords Test: "Bowling at that chap Mackay is like bowling at Westminster Abbey!"

Despite this magnificent effort at Lords, the next year Mackay was surprisingly left out of the Australian squad to tour South Africa – which was why, as a schoolboy, I wrote a letter of complaint to Sir Donald Bradman, who was Chairman of Selectors.

The next week a player withdrew and Slasher was included.

Australia won those four Tests in South Africa with Slasher Mackay averaging a Bradmanesque 125 an innings. He thus became a fulltime member of Ritchie Benaud's world beaters until 1963.

Benaud himself described Mackay as “the best team man I ever had”.

Mackay became such a hero at home that when he finally batted in his first-ever Brisbane Test at the Gabba (I was there) the standing ovation he received as he came out on to the ground, while he waddled all the way to the wicket, while he took guard, and while he raised his cap twice to the crowd, just kept on going.

A loudspeaker announcement had to be made to get everyone seated again so the match could continue.

Yet Slasher not once scored a century for Australia.

A hero who didn't even make it into the nervous nineties, an idol who averaged just 33.5 an innings.

This was because Mackay – who batted first wicket down for his state – was always sent in down in the lower order in Test matches at number seven or eight, propping up the innings.

Like the Test in Brisbane when Australia were six for 140 against England.

As British sporting writer Crawford White wrote: "When Mackay came to the wicket late on Friday the Australian innings had been broken, but when he shuffled off at 87 not out on Saturday afternoon 400 glorious runs littered the Gabba scoreboard."

Batting at the bottom of the order, Slasher set record last wicket partnerships twice – in 1957 in South Africa, and in1960 against the West Indies – breaking his earlier record.

He was also a valuable bowler, though again there was no flamboyance, just what looked like a struggle to get to the wicket. As with the bat, Slasher was mainly a man to hold things together with the ball and slow the opposition down.

When Australia undertook its first Test cricket tour to Pakistan in 1959 they found they had to bat on matting wickets … which they’d never seen before.

Slasher surprised by taking six wickets for 42 in the First Test to lead the victory – revealing later that he had sent to Pakistan for a matting wicket which he installed in his Nundah backyard and practised bowling on it.

In the 1961 Ashes tour of England, as a part-time bowler, he took three wickets with four balls dismissing three of their finest batsmen … Ken Barrington, M.J.K. Smith, and Subba Row.

But Mackay should be remembered for all time for what he did in the Fourth Test against the West Indies in the 1960-61 series.

Australia had only a few wickets to fall on the last day in Adelaide and the powerful West Indies would level the series with one Test to play. So, when we all went to bed the night before, the match seemed all but over … except, except, except that Slasher Mackay was still in there.

Wickets fell consistently as the day wore on until Mackay stood alone with spin bowler and last batsman Lindsay Kline ... yet there was still two hours to go against a West Indian attack boasting world stars Wes Hall and Garfield Sobers.

Frightening.

I went to a film with Ken Fletcher, and we couldn’t believe it when we got home, and Slasher was still chewing gum and batting.

All day, people kept giving up and leaving their wirelesses and TVs for an hour or two … and coming back to find Australia, inexplicably, still batting.

"He can't do it," people kept saying, to keep themselves from hoping for the impossible.

But with 30 minutes to go Slasher was no longer the only person who thought he could do it and force a draw. Taking just a single off the last ball of almost every over (eight balls in those days) he made sure that he faced almost every ball instead of Kline.

No attempt to score other than this.

With 10 minutes to go Mackay is surrounded by fieldsmen.

The ABC announcer says gravely: "Every man on the field, except the bowler, could pick Mackay's pocket."

The last ball of the second last over: Slasher scores a single to ensure he is the one who will face the last over against the fastest man in the world, the giant Wesley Hall.

"Mackay needs a snorkel tube to breathe," says the announcer, "the fieldsmen are all so close."

Twice Slasher is hit, but seven balls have gone.

Hall runs in for the eighth and final ball of the Test … loses his run-up, and the crowd, thinking it was all over, has to be cleared from the field.

The match has run 10 minutes over time – but, under the rules of cricket – the over, not being over, must be completed.

Mackay chews on and on, nonchalantly shrugging at the wicket.

Hall puts his country into the last ball, it rears up at Mackay's rib cage. The 10 fieldsmen surrounding Slasher rise from their crouches – their hands outstretched – expecting a deflection as the left-hander defends himself from the 90-mile-an-hour red projectile.

Mackay, seeing the ball cannot possibly hit the wicket, pulls his bat away with his left hand at the last second allowing the ball to crunch into his exposed right side.

As he doubles up, the crowd rises as one at the ground and around their wirelesses.

For, like Horatius at the bridge, such a gallant feat of arms was never seen before.

The match was saved. The series saved. Australia saved.

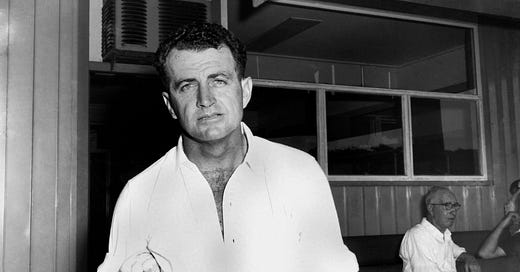

Pictures of the bruise left by that last ball – with Slasher holding up his shirt – made all the front pages.

Ken Mackay was a hero.

But not for long.

Oh they gave him an MBE, but within two years he had reached his use-by date and returned to his wife and four daughters and suburban obscurity in Rode Road, Nundah, in Brisbane.

He had played two hundred First Class matches, including 100 Sheffield Shield games for Queensland.

Slasher went back to his business of selling insurance in a tiny room with three salesmen and three desks and three phones.

For fifteen years he was a Queensland cricket Selector – until 1979 when he was unceremoniously dropped.

Slasher was slashed.

Horatius forgotten.

JUNE 1982: EIGHTEEN MONTHS LATER

Last week I went to the filing cabinet and took out a file marked "Mackay, Ken (Slasher)" with the intention of throwing it away.

They had just held his funeral, aged 56, and I wasn't going to need it any more. But when it came to the moment, I couldn't actually put it in the bin. Not because Mackay was an Australian sporting champion but because he was our most unlikely hero.

I grew to love Mackay mainly because of what he wasn't: he wasn't handsome, he wasn't tall, he wasn't well built, he wasn’t elegant.

He limped on both legs (said to be a result of “infantile paralysis”) and when he batted he stabbed, and crouched, and leapt, and jabbed … as if to prove that it was not coached strokes that kept him at the crease.

So much so that an English sports columnist wrote of a Mackay Test innings: "The man who pulls the strings on the puppet that is Ken Mackay batted particularly well today."

As he waited for the ball, Mackay's jaw traced large circles as he apparently nonchalantly chewed his gum; his body wriggling the opposite way; his right hand constantly adjusting his protective devices.

And, when he finally did face up to the bowler, there was no flourish of the willow: just a poke, with no back lift at all, to leave not the slightest chance that he might get out.

Admittedly it didn't look the best. Peter May's comment about Mackay "squirting" the ball instead of hitting it, wasn't too unkind. But that stroke was surely the reason why Mackay – before any cricketing Adonis – was the man to bat for your life.

He didn't come from the right background – not a Melbourne public school, not even a Queensland private school.

Just Virginia State School in a poorer part of north Brisbane.

Perhaps that is the real reason why Slasher didn't get in his country’s Test team until his 30th year, even though he had been one of the top couple of scorers in the country.

But the Adelaide, Sydney, and Melbourne Cricket Clubs thought his technique was poor, and, besides, he wasn't a good advertisement for the sun-bronzed Aussie. He looked untidy.

Of course no one ever actually said that, but that's what they thought.

Anyway Slasher kept proving them all wrong.

Although he batted first wicket down for Queensland, at the end of his career it was noticed that he held the state record for the number of times not-out. That is, he was often batting right through the innings! An unheard-of record – and all because he refused to see his weak state side beaten.

By chance, I had a drink with Slasher a few weeks before he died.

It was at a huge function at the state's new Cultural Centre on the river in Brisbane. The champagne was free, the hors d'oeuvres were brilliant when Slasher ambled slowly over.

I had written a feature on his heart attack a year before and I knew that was why he was heading my way.

We stood awkwardly for a moment, hero and hero-worshipper, eating bacon wrapped round prunes.

Then Slasher put down his champagne glass, put his hand in his suit pocket and pulled out a half-empty packet of chewing gum and offered me a white one saying only: "Gum?"

I didn't want it.

I couldn't drink champagne and eat prunes and chew gum.

Not all at once.

But I took the gum.

As we chewed together, Slasher told me about his first alcoholic drink:

"I vowed I would never have a beer until we beat New South Wales at the Sydney Cricket Ground," he said, "And when we did – many years later – the whole team was waiting for me with a glass of beer as I walked off the SCG." (Mackay was still batting at the end, of course.)

That was my goodbye to Slasher.

I wish now I'd kept the gum.

That is a warming story from our past, giving us all a boost just when we need to believe there is hope again. Your hero's doggedness and persistence is a beacon, showing us that it is worth "sticking to your guns".

Hugh, your title is so very true when we remember one hero we can tend to forget other heroes

The way you tell the story was excellent